BBC Proms: Schiff, Hallé, Elder | reviews, news & interviews

BBC Proms: Schiff, Hallé, Elder

BBC Proms: Schiff, Hallé, Elder

Top pianist's Bartók shines amidst interpretatively mixed masterworks

It was partly as penance for having missed the previous evening's Czech festival that I arena-prommed for last night's Moravian finale, to be happily strafed by the nine extra trumpets of Janáček's Sinfonietta.

Let's not underestimate the enterprising Elder for his part in giving us the Proms premiere of Sibelius's second suite transforming the advertised "historical scenes" into ageless tableaux, the charming ideas cast in earlier days as music for a Finnish pageant but reforged in 1911 with the quirky mastery of his maturity following labour on his most austere masterpiece, the Fourth Symphony.

How could we not love, within the silky intimacy the Albert Hall can paradoxically provide if the conductor judges it correctly, the little kicks Sibelius gives to his tiny themes and figures at unexpected points in the symphonic argument of the opening movement, "The Hunt" with its long-delayed Tchaikovsky touch, his singular and uncharacteristic incorporation of a harp in a restrained lovesong, or the winsome lone flute refrains that tease out the minimal, magical final pages of "At the Drawbridge"? Here Sibelius the flawless, tuneful miniaturist and the symphonic master who never peaks too soon meet in as fine a score as any he wrote.

Which is not quite the same thing as a pecking order of seriousness, at the very top of which stands the economical Seventh Symphony as the apotheosis of the Finn's ever-developing art. Elder's performance began well, with careful colours and added violin vibrato in the multi-part string hymn that leads to the first mountain peak - superbly natural work here from Hallé first trombone Gary McPhee. But then it all lost impetus as Elder adapted to Sibelius's many tempo changes with the clunk of a noisy clutch: inorganic and anything but inevitable, however lovely many of the sounds along the way. In that respect, Elder seems determined to honour the stolid memory of a great but often maddening predecessor in Manchester, Sir John Barbirolli, whose treacly Sibelius now sounds almost unbearable against the lither visions of Paavo Berglund and Jukka-Pekka Saraste. As did this.

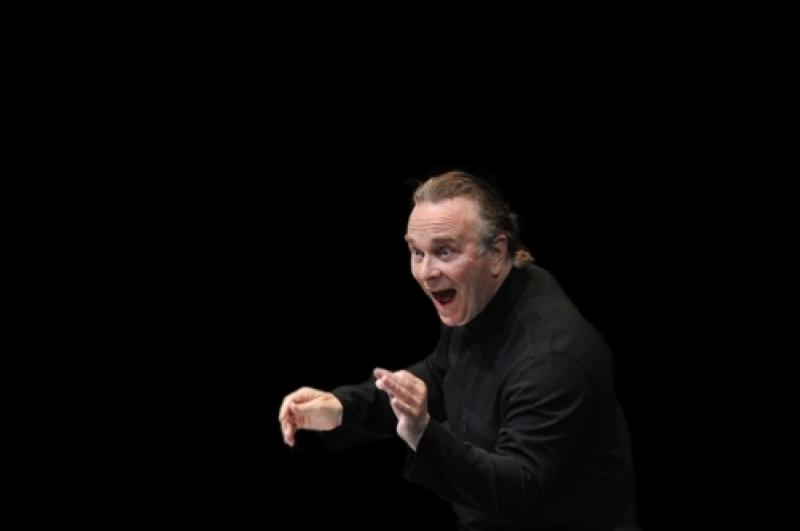

In Bartók's Third Piano Concerto after the interval, it was that noble Hungarian András Schiff (pictured right) who kept the seeming spontaneity fine tuned. It's some time since I heard this work in concert, but so effortless and inevitable did Schiff make all the connections in what can sometimes seem like a disjointed if not over-simplified late work - composed as a kind of insurance policy for the fluent but not over-virtuosic talents of Bartók's wife, Ditta Pásztory - that I sensed what was coming next. And that, of course, always in a good way. If the opening didn't always have the pearly lightness we're used to, Schiff found plenty of that in a playful second theme, and meshed so touchingly with the buzzing, chirping nature nocturne at the heart of the slow movement. His encore, Schubert's ineffable Hungarian Melody (the Bartók had led me to expect Schiff's beloved Bach), extended the ease in a rolling-plains movement that could have held us spellbound for much, much longer.

In Bartók's Third Piano Concerto after the interval, it was that noble Hungarian András Schiff (pictured right) who kept the seeming spontaneity fine tuned. It's some time since I heard this work in concert, but so effortless and inevitable did Schiff make all the connections in what can sometimes seem like a disjointed if not over-simplified late work - composed as a kind of insurance policy for the fluent but not over-virtuosic talents of Bartók's wife, Ditta Pásztory - that I sensed what was coming next. And that, of course, always in a good way. If the opening didn't always have the pearly lightness we're used to, Schiff found plenty of that in a playful second theme, and meshed so touchingly with the buzzing, chirping nature nocturne at the heart of the slow movement. His encore, Schubert's ineffable Hungarian Melody (the Bartók had led me to expect Schiff's beloved Bach), extended the ease in a rolling-plains movement that could have held us spellbound for much, much longer.

Elder's way with the Sibelius symphony boded less well for the forward momentum of Janáček's Sinfonietta - and so it proved, despite the ever-thrilling panoply of brass fanfarers who introduce and crown the work, all 13 of them unlisted in the programme. There was a lush, dreamy quality about the short-lived nocturne depicting the Queen's Monastery in Brno; then trombones rasped, piccolos fluttered in panic, horns whooped grotesquely and the stressy chain of woodwind command in the final struggle before the dawn elicited spectacularly full tone.

Yet this Sinfonietta didn't have half the driven energy the veteran Sir Charles Mackerras found here even in his last years, and though it was good to hear the quirky showpiece in the Albert Hall, there was nothing like the same sense of theatre as Janáček makes one final crazy modulation before the blaze of the last chord: odd from such an experienced opera conductor. Still, it was good to hear the quirky showpiece in the Albert Hall, and just like old times to be standing in a packed arena in the distinguished company of a major classical CD producer and other knowledgeable, offbeat folk. There's nowhere else quite like it; note to self to try and get back down there more often.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Comments

...

...