theartsdesk in Flanders: Return to Journey's End | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Flanders: Return to Journey's End

theartsdesk in Flanders: Return to Journey's End

Regular visits to WW1 trenches help to keep a classic stage play visceral

The battlefields of the First World War are frequented most by secondary school groups and military history enthusiasts. And by David Grindley: a man for whom the play Journey’s End is an obsession, and his direction of it award-winning. RC Sherriff's play follows a group of British officers preparing for battle in frontline trench warfare, and which places “ordinary men into extraordinary circumstances”. This month sees Grindley’s production returning to the West End.

The combination of an all-male cast, two of the three lead characters being under 21, and its setting in just one room, has made theatres consistently resistant. Grindley was given the directorial reins after a 12-minute meeting in 2002, which he ended by shouting, "I’ll make the most definitive production of this play ever!" He admits he thought the claim "a bit silly", even at the time. Even so, it took six months and a fortuitous glance inside the paperback cover of RC Sherriff’s play to get it on stage.

“Just when it was looking like it was all going to fall apart," Grindley explains, "I looked at the text and read that the play was first performed on 21 January, 1929. At that moment, I realised that 21 January, 2004 would be the 75th anniversary. If we missed that night, there would have been no point going on.” The hook worked. After initially being given an eight-week run, Grindley’s production did 18 months in the West End, followed by two national tours and a transfer to Broadway, where it won a Tony Award for Best Revival.

A major part of Grindley’s success was his determination to make the play “hyper-real”. As well as Broadway-standard sound equipment (which sends sound waves from bomb noises reverberating through the audience), Grindley and his designer Jonathan Fensom have relied upon repeated visits to the battlefields of Northern France since 2003 to make the show a thoroughly visceral audience experience.

Although the play is set in Saint-Quentin, in Aisne, Grindley has explored the areas around Lille over 100 kilometres to the north to inform his production. We visit three sites, located amongst the high ridges of the area known to the French as Artois, north of Arras, which look over the plain of Douai. It was at the start of the First World War in 1914 that these ridges and the agriculturally and industrially important plain were captured by the Germans.

Although the play is set in Saint-Quentin, in Aisne, Grindley has explored the areas around Lille over 100 kilometres to the north to inform his production. We visit three sites, located amongst the high ridges of the area known to the French as Artois, north of Arras, which look over the plain of Douai. It was at the start of the First World War in 1914 that these ridges and the agriculturally and industrially important plain were captured by the Germans.

The area saw consistent and brutal fighting as Allied forces attempted to reclaim the land, until a major attack was launched during the Battle of Arras in 1917. Unlike Saint-Quentin, of which there is no record of the damage caused by Operation Michael – the attack with which Journey’s End finishes, and the only time the Germans successfully broke Allied lines - Artois is dotted with cemeteries, monuments and preserved trenches and tunnels in varying stages of upkeep.

Today the area is reminiscent of the sleepy provincial towns of Encore Tricolore textbooks. Boxy tiled houses with neat gardens and the occasional café awaiting morbid tourists interrupt vast farming land which, less than 100 years ago, was the scene of mass human destruction. It doesn’t help that the weather is thoroughly miserable – we are reminded that, were we the unfortunate protagonists of Sherriff’s text, we would be wading through water as a result of the heavy showers – but there is a sombre air about the place.

It’s one that keeps luring Grindley back: “I never fail to be moved by coming here,” he says. “You just see the thousands and thousands of graves, there always seems to me to be an enormous sky, you can just feel the weight of that experience remaining.”

The French National Memorial and Cemetery, Notre Dame de Lorette, is our first stop. Located on a hill which was one of the major military objectives during the Second Battle of Artois, it contains some 40,000 graves, half of them for unknown soldiers. Beyond the sea of neat, white crosses, the views across the plain are vast.

The French National Memorial and Cemetery, Notre Dame de Lorette, is our first stop. Located on a hill which was one of the major military objectives during the Second Battle of Artois, it contains some 40,000 graves, half of them for unknown soldiers. Beyond the sea of neat, white crosses, the views across the plain are vast.

Where a white, almost too decadent chapel now stands, a maze of German tunnels, trenches and strong points known as The Labyrinth existed in 1915. Behind the cemetery, a few sheep graze on part of the original front line. It’s initially difficult to work out what you’re seeing, amongst a muddle of deep ditches, barbed wire and some heavy industrial artillery laid to rust in the ever persistent drizzle.

“It’s quite ad hoc,” admits Grindley, “but that’s what I like about it.” When he and Fensom first visited the site eight years ago, they jumped the fence to take a look. What they found, and what we’re discovering now, are two trenches – one English, one German – a mere 20ft apart. “It looks false, the proximity looks a little too close,” admits Grindley, “but it isn’t the case.”

The short walk between the two gives ironic weight to Journey’s End character Raleigh’s belief, like many other optimistic young recruits, that the war was one big rugger game – the frontline is about as wide as a pitch. It’s also difficult to imagine the churned mud, burnt-out trees and monochromatic, shell-holed nothingness that these trenches occupied – there’s a post-shower freshness in the air, sheep are bleating and birds fly above.

The short walk between the two gives ironic weight to Journey’s End character Raleigh’s belief, like many other optimistic young recruits, that the war was one big rugger game – the frontline is about as wide as a pitch. It’s also difficult to imagine the churned mud, burnt-out trees and monochromatic, shell-holed nothingness that these trenches occupied – there’s a post-shower freshness in the air, sheep are bleating and birds fly above.

Although Grindley emphasises the loudness of the bombs in his production, it is the quiet which is far more prevalent throughout the play: “A lot of the play is very quiet, because it was.” He says that, “That was the most scary thing – all this greenery here, all this would be shot to shit. There was a very eerie, unworldly silence, punctuated by moments of extreme violence. The men only did six days on the frontline, but they would be the scariest six days of your life.”

One of the main differences, Grindley says, between his production and those prior to it is the vigour and urgency of the men and their interactions with one another. Fear is a key part of what holds the men together in the play, as well as causing the displacement strategies which are responsible for its most poignant and comedic moments.

We are taken to Vimy Ridge, which Grindley visited to try and quantify the terror. In Journey’s End, Stanhope mentions Vimy Ridge as a turning point for his dependency on whisky to cope with trench life. A failed night-time attack at the site caused one company to lose 95 out of 100 men, while the surviving five had to shelter under bodies and dying men until the next nightfall to return to camp.

It’s an experience which stuck with Grindley: “I thought that was a brilliant thing to tell an actor. ‘This is what happened to Stanhope. A hundred men went up that hill, the machine gun fired, and you were leading them. You survived. How would that feel for you?'”

The site is now covered with thick pine trees, and the huge mine craters, roughly eight metres deep and wide which occupy a one-time no-man’s-land, are grassed over and attracting the attentions of visiting schoolboys. Underneath these, however, is a network of preserved tunnels which helped the Canadian forces finally to take the area from the Germans. The tunnels were the influence behind Grindley’s compact staging.

The site is now covered with thick pine trees, and the huge mine craters, roughly eight metres deep and wide which occupy a one-time no-man’s-land, are grassed over and attracting the attentions of visiting schoolboys. Underneath these, however, is a network of preserved tunnels which helped the Canadian forces finally to take the area from the Germans. The tunnels were the influence behind Grindley’s compact staging.

“The set is very small,” he says. “That is deliberately a choice of ours, seeing what we saw at Vimy Ridge, at how limited the space was that these people operated and lived in, and what sort of effect that claustrophobia of being penned in, like sardines, would have had on them. That awareness, that they were almost being buried alive.”

The tunnels we are shown around were remarkably well constructed – although they are still prone to caving in. They are only representative of the dugouts evoked in Journey’s End in size. These, more equitable to those in Sebastian Faulks’s Birdsong, were the handiwork of miners. However, troops still occupied them for up to 48 hours before going out to greet the front line on a snowy winter’s morning.

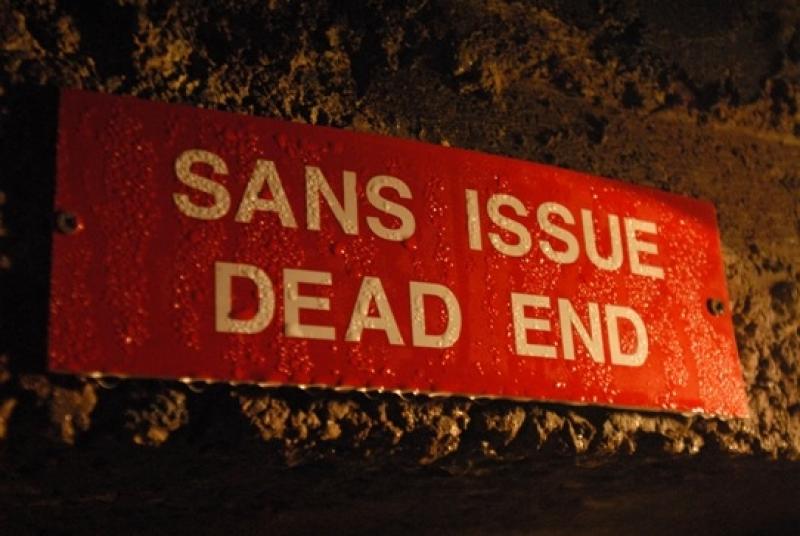

They are damp, the air is noticeably thinner, algae grows on the porous chalk walls. Men drowned down here by flooding. At the end of the tunnel, a room with two wooden bed frames, chicken wire laid across them, hint at bunk beds stack two, four or five high, which directly influenced Fenson’s design.

They are damp, the air is noticeably thinner, algae grows on the porous chalk walls. Men drowned down here by flooding. At the end of the tunnel, a room with two wooden bed frames, chicken wire laid across them, hint at bunk beds stack two, four or five high, which directly influenced Fenson’s design.

Another aspect of Journey’s End’s hyper-reality is the darkness. Great efforts have been made to hide the traditionally exposed theatrical lighting in Grindley’s production. We are treated to the tunnels without safety lighting. Even with double the light sources that would have been here originally (every 10 metres, rather than every 20, and natural light from the entrance), I cannot see the person standing two feet away from me.

We end the day at the Loos memorial at Dud Corner Cemetery, outside the village where RC Sherriff’s battalion, the Ninth East Surreys, fought, as well as at Vimy. Situated, like many of the cemeteries, on the side of a road, it resembles an English garden in the fleeting sunshine. Red roses line the white, solid gravestones. There are more than 1,000 here, with another 20,000 names listed on the memorial walls. Of the gravestones attributed to a known soldier, the majority are the resting places of men aged between 18 and 22. The generation gap between the men in Sherriff’s play is another aspect which Grindley was insistent on realising.

“We have to believe that Stanhope is 21, and that Raleigh is 18,” he says. “Osbourne and the others have to be a generation older. We have a real sense of boys leading men.” Grindley was 19 when he first read the play, and his similarity in age to some of its characters was one of Journey’s End’s most resonant features for him, and why he retains belief in the play’s continuing resonance nearly a century on from the events it portrays.

I ask Grindley if he has seen the recent BBC Three series Our War, which comprises digital-camera footage from soldiers in Afghanistan. He hasn’t, but it seems to prove his point about Journey’s End’s humanity and the prescient portrait of all wars to come. Over lunch, he says that Journey’s End is “the show. My life-defining show. No question”. I can’t help but feel, as we tread in the footsteps of soldiers who fought decades before on the Western Front, his production will continue to ring true as another generation of soldiers fights today in similarly brutal conditions.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment