BBC Symphony Orchestra, Renes, Spitalfields Music | reviews, news & interviews

BBC Symphony Orchestra, Renes, Spitalfields Music

BBC Symphony Orchestra, Renes, Spitalfields Music

Christ Church vibrates with downsized Mahler, Van der Aa and two great soloists

Everyone in the BBCSO is a potential soloist. I know this because the course I run at the City Literary Institute linked to the orchestra has welcomed principals, duos, two string quartets and three viola foursomes (proving that department the most individual, not the dense deserving butt of many a joke). I adore these players, but I love Erwin Stein's chamber arrangement of Mahler's Fourth Symphony even more, so this was bound to be a gem.

Not a bad one at all, as it turned out; its pre-interval airing gave breadth and imagination to the programme, and offered us the first of the evening's two outstanding vocal soloists. I haven't seen enough of mezzo Stephanie Marshall since she made such an impact as heroine Offred in Poul Ruders's ambitious operatic setting of Margaret Atwood's masterly novel The Handmaid's Tale. And to be honest I didn't get enough of her last night either, finding myself in the very Christ Church Spitalfield sightline where she was blocked for me both visually and aurally by accomplished stick-wielder Lawrence Renes. Still, it was enough to tell that she opulently coasted the more thickly scored orchestral washes of Van der Aa's Spaces of Blank, and did what she could with some not exactly memorable word-setting of evocative texts by Emily Dickinson, Rozalie Hirs and Anne Carson.

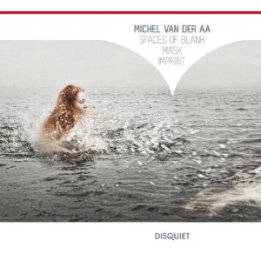

The common bond is the terror and the beauty of infinite space, the former most striking when the fog of city streets conjures up a hallucinatory, jazzy juggernaut at the heart of the second movement. At least Van der Aa is asking some of the big questions, though I don't know what annotator Bas van Putten means by "the orchestra becomes not so much an instrument of overt feelings than [sic] a study object". What I do know, from listening both to this and the 2009 premiere recording enterprisingly released on Van der Aa's Disquiet multi-media label (pictured above), with the equally compelling Christianne Stotijn as soloist, is that, while rhythms and bass lines keep the listener engaged, the orchestral ideas aren't sufficiently individual or strikingly clothed to bear repeated listening, and while the brass begin with hieratic chords, the strings are asked to saw away generically. Nor does the soundtrack evoke as much as was apparently intended, though it may not have been in precise synch last night. Traffic noises? Oh, that's the street outside the church.

The common bond is the terror and the beauty of infinite space, the former most striking when the fog of city streets conjures up a hallucinatory, jazzy juggernaut at the heart of the second movement. At least Van der Aa is asking some of the big questions, though I don't know what annotator Bas van Putten means by "the orchestra becomes not so much an instrument of overt feelings than [sic] a study object". What I do know, from listening both to this and the 2009 premiere recording enterprisingly released on Van der Aa's Disquiet multi-media label (pictured above), with the equally compelling Christianne Stotijn as soloist, is that, while rhythms and bass lines keep the listener engaged, the orchestral ideas aren't sufficiently individual or strikingly clothed to bear repeated listening, and while the brass begin with hieratic chords, the strings are asked to saw away generically. Nor does the soundtrack evoke as much as was apparently intended, though it may not have been in precise synch last night. Traffic noises? Oh, that's the street outside the church.

Say what you will about Stein's scaling-down of Mahler's most Neo-Classical, chamber-conscious symphony to a string quintet, selective woodwind, percussion, piano and harmonium, but it's never less than rewarding for the players, even if balances - especially in reverberant church acoustics - can be a headache. Surely, too, this is a more successful realisation than what Stein's colleague in the pioneering Viennese Society for Private Musical Performance, Schoenberg, made of Das Lied von der Erde. The main thing is that you learn more about the essence of the symphony than you miss. There were some curious revelations as the sleigh ride of Mahler's first movement heads into dark woods: here it was the notably biting oboe of the excellent Richard Simpson, joining forces with Richard Hosford's hard-worked clarinet - he has to substitute horn and trumpet too - which seemed the most feral beast in the jungle: a lurking predator waiting to snap at the Viennese sweetness of first violin Stephen Bryant.

Yet as Bryant exchanged his standard fiddle for another differently tuned, he became the acid bogey man of the scherzo. Renes's lively control, allowing just enough space for relatively relaxed country-idyll trios, and the fraught textures made this a more than usually hallucinogenic dance of death with an eerie coda that seemed to conjure up the alleged demons of Hawksmoor's mysterious edifice. The alternating serenity and sorrow, innocence and experience, of Mahler's great slow movement have surely never sounded more vivid, with the underlying bell-tolling figure much more apparent throughout than usual given the clarity of piano doubling double bass. It says much, on the other hand, for Malcolm Hicks's understated mastery that the harmonium, least lovely of thickening agents, only occasionally sounded a Gothic or lugubrious note, and never oppressed the textures as it so often can. Renes might have relaxed just a shade, encouraged a little more in the way of infinitely soft dynamics, but this was certainly an interpretation which gathered weight and wonder as it progressed.

So the best really did come, for once, in Mahler's intended pinnacle: the seraphic cloud-clearing which paves the way for the final child's view of heaven, and the incandescent, text-conscious perfection of the song apotheosis, soprano Sarah-Jane Brandon (pictured left) handling every tricky if rewarding phrase with profound musical intelligence. I've never heard it sung quite as poignantly as this, and that's saying something given that on the last two occasions, the more erratic Christine Schäfer was the soloist in the full-orchestral original. On the other hand I may have been experiencing a high of well-fed contentment on hearing the calves' brains and asparagus I'd consumed at a fabulous restaurant two blocks down so blithely evoked. For Mahler sanctifies both in the culinary list of his most bittersweet and ultimately stilling symphonic finale. What bliss.

So the best really did come, for once, in Mahler's intended pinnacle: the seraphic cloud-clearing which paves the way for the final child's view of heaven, and the incandescent, text-conscious perfection of the song apotheosis, soprano Sarah-Jane Brandon (pictured left) handling every tricky if rewarding phrase with profound musical intelligence. I've never heard it sung quite as poignantly as this, and that's saying something given that on the last two occasions, the more erratic Christine Schäfer was the soloist in the full-orchestral original. On the other hand I may have been experiencing a high of well-fed contentment on hearing the calves' brains and asparagus I'd consumed at a fabulous restaurant two blocks down so blithely evoked. For Mahler sanctifies both in the culinary list of his most bittersweet and ultimately stilling symphonic finale. What bliss.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

Add comment