Ballet's Bad Girl Has a New Sound | reviews, news & interviews

Ballet's Bad Girl Has a New Sound

Ballet's Bad Girl Has a New Sound

New orchestration of MacMillan's classic Manon settles old scores

Kenneth MacMillan’s dramatic ballet Manon was premiered in 1974 to a chorus of attacks on its tale of a “nasty little diamond-digger”, as one critic had it. Since then the slut who can’t help herself has risen to become one of the most coveted roles in the world for major classical ballerinas (as another critic at the time foresaw), and the ballet is now in the repertoire of some 18 companies around the world.

But one problem has remained constantly noticed - a sense that its orchestral score, a medley of Massenet arranged by Leighton Lucas, could do better justice to the story. Last weekend a new version of the score was premiered at the Finnish National Ballet in Helsinki, when they also premiered a new production of the ballet. And MacMillan’s widow has declared that from now on this will be the standard orchestral score. Later this year, when Manon returns to the Royal Ballet repertoire, it will be with the new orchestration by longtime Manon conductor Martin Yates.

Yates has taken a really serious look at the Massenet originals and intelligently married nuances of orchestral colours to the choreography so that the sounds from the pit complement the unfolding story in the dance: the drama and its emotional sub-text building properly together over the full span of the evening.

“I’m delighted that Martin has kept the essence of the old score, but solved its inherent problems,” said Lady Deborah MacMillan after the premiere. “He’s done much more than the ‘tidying up’ that he was asked for, and has really married the music to Kenneth’s choreography so that it now sounds as if it’s always been an integral part. Martin clearly has a passion for Massenet’s music, a respect for Leighton Lucas’s and Hilda Gaunt’s original intentions – and yet has refreshed and revitalised the music – and so the ballet.”

The strength of Manon has always been that MacMillan’s choreography allows every intelligent dancer who comes to the work the freedom to find something new in this complex character, to bring a new perspective to the dramatic truth even while being faithful to the original steps. And yet I’ve rarely felt that the original Leighton Lucas arrangement of Massenet’s music properly complements these nuances that might be revealed on stage. It’s always seemed too fruitily romantic from the very start, pumping up the love story into heights of passion before anyone has even begun to hold hands, and equally, blasting across the narrative with strangely vulgar contrasts in rum-ti-tum and bombast; the circus suddenly erupting into the bedroom. And again the succession of pieces exist in separate aural environments almost as a series of disparate events, rather than the emotional partner to a cohesive narrative.

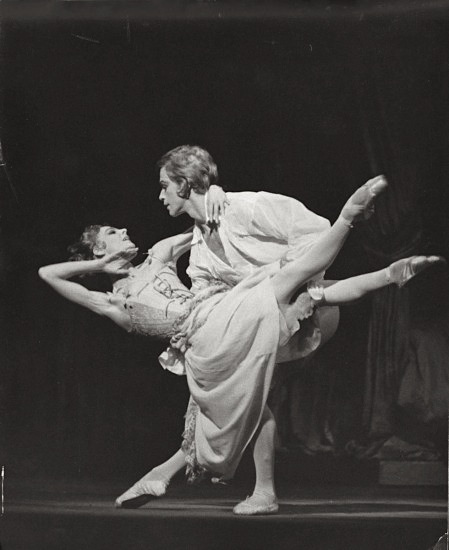

Originally the company pianist Hilda Gaunt found reams of Massenet for MacMillan to consider, all avoiding his opera Manon: music from other operas, songs, piano pieces. These were whittled down to more than 40 different musical episodes suitable for the story – which were then orchestrated by Lucas for the 1974 premiere. (Pictured right, the original Manon and Des Grieux, Antoinette Sibley and Anthony Dowell, photo by Jennie Walton/ROH Archive.)

Originally the company pianist Hilda Gaunt found reams of Massenet for MacMillan to consider, all avoiding his opera Manon: music from other operas, songs, piano pieces. These were whittled down to more than 40 different musical episodes suitable for the story – which were then orchestrated by Lucas for the 1974 premiere. (Pictured right, the original Manon and Des Grieux, Antoinette Sibley and Anthony Dowell, photo by Jennie Walton/ROH Archive.)

From indications in the original score and orchestral parts, it looks to have been a rush job. MacMillan never thought it to be ideal, but there wasn’t time, or the money, or the inclination from the management at that time to do anything about it. Later, the conductor John Lanchbery attempted a re-orchestration which MacMillan rejected, so the status quo remained until the Royal Ballet indicated to Martin Yates that they’d be interested if he would “tidy it up”.

Leighton Lucas had to orchestrate “blind”, as it were, before he saw anything on stage. Yates’s advantage is that he’s worked with the choreography which he knows very well from conducting so many performances. Furthermore, his experience is not only in ballet, but also opera, with symphony orchestras; he’s done a lot of composing and reworking of scores. He also has an invaluable experience of the dramatic imperatives of showbiz, having worked as music director on some of the most successful productions in commercial theatre such as Hal Prince’s Phantom of the Opera, Trevor Nunn’s Sunset Boulevard and Nicholas Hytner’s Miss Saigon and Carousel – which was the last choreography that Kenneth MacMillan did before he died in 1992.

Martin Yates soon saw that his job on Manon was to do much more than “tidy up”. “I went right back to the original Massenet scores to see what exactly he had done in his own orchestration and I’ve tried always to preserve the integrity of the original. I haven’t thrown things out. But the old Lucas score sounds really like music for a series of diverts, where the ballet itself isn’t. That’s not to say it wasn’t a masterpiece of stitching, to choose the right piece of music for what MacMillan was doing in the choreography.

“One concern in the Lucas orchestration is the size of orchestra, which changes quite significantly from one piece to the next: I’ve tried to rationalise the scoring so that the end result sounds as if it is music from the same composer. I have hardly changed the size of orchestra - the only instrument people will miss is the celeste, and probably not even that as it only plays in a tiny part of the evening. But I have rearranged the parts; re-allocating the music for the three trumpets, for example, so they each have a decent share to play. Likewise with the three flutes. In the first scene I now have two harps, which makes for a different texture.

“Dynamic markings are also important; Massenet might have put a single indication across the whole score and that would have worked for the orchestra of his time – but instruments have developed so that these days the balance has to be carefully thought out. Where some groups might be playing forte, the brass should be marked down – mezzo forte or even less – to balance.

“Sometimes the changes are only very minor details of voicing. I’ve pruned quite a lot when necessary, cutting out some of the textures. But, for example with the Waltz in Act II in Madame’s party , I took it all apart and started again. It’s such a good tune, it deserved better!”

Audiences will hear a more refined sound world in the opening prelude, a setting of the famous "Last Sleep of the Virgin" which breathes into the theatre with a hushed, mystery before the tunes emerge.

“I’ve taken the music from a different part of the original and revoiced it to establish the solo cello and the violin – the cello being such an important element in the music through the ballet,” explains Yates. “I know Kenneth MacMillan is described as a choreographer, but technically he’s also the director of the drama. When I worked with him on the National Theatre’s production of Carousel, particularly on orchestrating the pas de deux, he really impressed on me that you tell the story through the orchestration. 'Don’t give it all away too soon,' he always said.

“So I’ve deliberately tried to build the weight of the orchestra so that it grows towards the end.”

Again in the famous "Élégie" for the first pas de deux in Act I, the music unfolds from a very discreet beginning with cello and oboe, building in intensity, with the action, until we get the orchestra in its full glory for the first time in the theatre.

- Listen to the theme of the first pas de deux in the new revision, the Finnish orchestra conducted in rehearsal by Martin Yates

In the second Act I pas de deux, in the bedroom, Yates uses chamber music textures, the orchestration translucent, coloured with solo lines from the woodwind.

- Listen to an extract from the second pas de deux in the new revision, the Finnish orchestra conducted in rehearsal by Martin Yates

Meanwhile, the outer wicked world is also there contrasting in brash and bustle: the soldiers and tarts, beggars and chancers, Madame and her clients. There’s a rich moment in Act II, after Manon has entered with Monsieur GM and has been shown off to the mesmerised company of punters, when Lescaut’s Mistress then takes to the floor accompanied by the ripest of strings, playing on the G string - which clearly indicates the practised good time she would be offering in contrast with Manon’s coolness.

The difference is in the detail of presentation: Manon’s theme (from the song “Crépuscule”) changing every time it comes back, the “Élegie” likewise until the agony in the final scene. Yates has restored Massenet’s original harmonies which effectively push the action forward – and there is one new piece of music which will not only serve to distract from the longueurs of a scene change in the Georgiadis production, but also gives the audience an emotional pause point (with a sensational solo for the cello) before MacMillan tightens the screws towards the end.

Below, photographs of the Finnish National Ballet 'Manon' by Sakari Viika with Julie Gardette (Manon), Friedemann Vogel (Des Grieux), Wilfried Jacobs (Lescaut), Henrik Burman (Monsieur GM)

[bg|/DANCE/ismene_brown/FNB_Manon]

The new scoring is particularly interesting when heard and seen in conjunction with the Mia Stensgaard designs which were made for the Royal Danish Ballet in 2003. This is the view of a young designer who conveys the period in her costumes without the need for any heavyweight emphasis: the set is also minimal, working with few backcloths and props, paring away anything inessential to the central action.

Consequently, it’s very open and exposed for the dancers and a considerable challenge for the Finnish company. There is room for not only the steps to be seen more clearly: in Act III on the port in Louisiana, there’s a sad moment for four deportees supporting each other centre stage which I only saw clearly for the first time in the Finnish production, but the story also gains room to develop all around the stage picture. In Act I we can clearly take in the moment when Manon and Des Grieux connect in the crowd, long before his first solo; in the brothel ballroom, Manon may be GM’s current property, but she has her eye out for backstop alternatives among the thronging men.

This is the first time that Finnish National Ballet have done a MacMillan: their artistic director Kenneth Greve danced in the 2003 Copenhagen Manon production, and was very keen from the start of his directorship in 2008 that his new company should enjoy the dramatic opportunity. He has a large group of dancers, some 85, who appear to have taken to the challenges with gusto. Not least with some interesting character cameos from the corps, relishing the chance to play beggars and whores, dirty old men and eager beavers – and a delicious confection of acid-drop tartlettes at Madame’s party. Madame herself (Ananda Kononen) is a richly rumbustious hostess. It’s very interesting, too, to see MacMillan’s choreography as taught from scratch from the notation with a company that comes to it without any historical baggage, and definitely making the work their own.

This is the first time that Finnish National Ballet have done a MacMillan: their artistic director Kenneth Greve danced in the 2003 Copenhagen Manon production, and was very keen from the start of his directorship in 2008 that his new company should enjoy the dramatic opportunity. He has a large group of dancers, some 85, who appear to have taken to the challenges with gusto. Not least with some interesting character cameos from the corps, relishing the chance to play beggars and whores, dirty old men and eager beavers – and a delicious confection of acid-drop tartlettes at Madame’s party. Madame herself (Ananda Kononen) is a richly rumbustious hostess. It’s very interesting, too, to see MacMillan’s choreography as taught from scratch from the notation with a company that comes to it without any historical baggage, and definitely making the work their own.

There are three casts of the principal characters: at the premiere Julie Gardette, in her first really major role, was utterly bewitching as Manon, whom she showed as a clever, bright girl who quite clearly knows the options open to her and yet can also be swept away by passion for the totally unsuitable (in career terms) Des Grieux. Partnered by Friedemann Vogel (who came in from Stuttgart to replace the injured Jaako Eerola) their two characters were intensely believable (the pair pictured left, courtesy Finnish National Ballet) – the “bracelet” pas de deux in Act II particularly, finely judged in the ebb and flow of the argument: will she leave the bling behind or will he have to tear it off her? One knew exactly what they were saying to each other.

Performances go on until 8 April by which time the choreography will really have bedded in to the company who in recent years have had a strong emphasis in contemporary works. Greve on the other hand comes from the classical traditions of the Royal Danes, burnished also by hard taskmasters such as Erik Bruhn, Baryshnikov and Nureyev. He’s asked a lot of his new company to engage with Manon – and on the premiere’s evidence, they’ve stepped up to the plate with enthusiasm.

- The Finnish National Ballet performs Manon again on 21, 23, 25, 28, 30 March and 2 & 8 April

- Manon also premieres with Estonian National Ballet on 7 April, and returns to the Royal Ballet rep from 21 April

- See what's on at the Royal Ballet. Read Royal Ballet reviews

- Read theartsdesk's interview with Kenneth MacMillan's biographer Jann Parry

- Read theartsdesk's interview with psychoanalyst Dr Luis Rodriguez de la Sierra: 'Ballet and Psychoanalysis'

- The Kenneth MacMillan website

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Comments

...