theartsdesk Q&A: Composer Michel Legrand | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer Michel Legrand

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer Michel Legrand

He worked with everyone: the veteran composer tells his life story

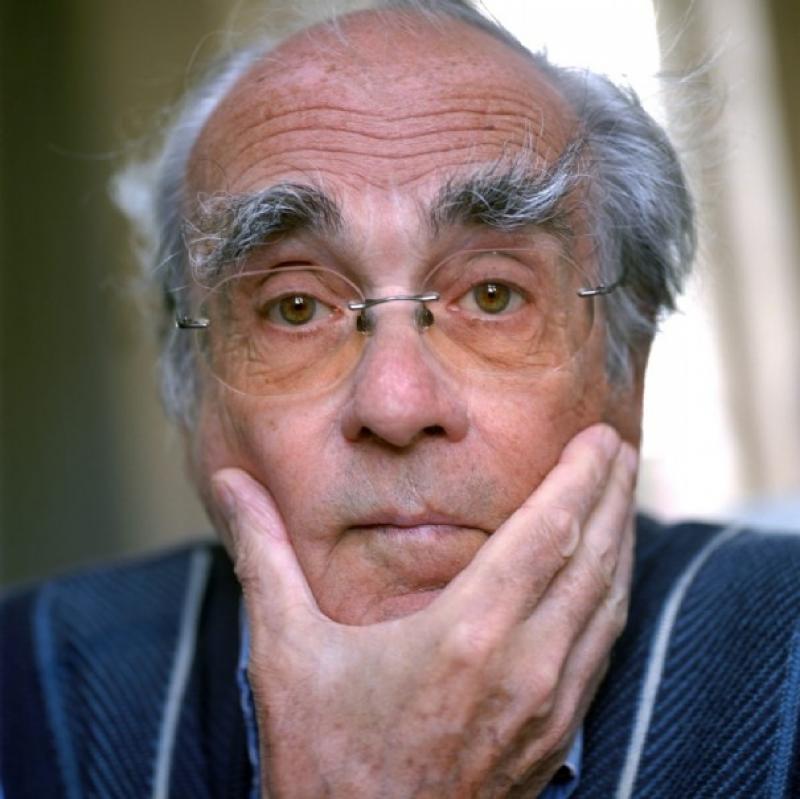

“I want to be a man without any past,” said Michel Legrand, who has died at the age of 86. He had perhaps the longest past in showbiz. Orchestrator, pianist, conductor, composer of countless soundtracks, who else has collaborated as widely - with Miles Davis and Kiri Te Kanawa, Barbra Streisand and Jean-Luc Godard, Gene Kelly, Joseph Losey and Edith Piaf? When I visited him at his house at his splendid classical manoir 100km south of Paris, on the mantelpiece in the large white sitting room four familiar gilt statuettes stood sentry. The oldest was for “Windmills of My Mind”, the best original song of 1965.

A child prodigy at the piano, he converted from classical to jazz under the nose of his disapproving teacher, the composer Nadia Boulanger. Initially he worked as an orchestrator; his earliest triumph was I Love Paris, a set of jazz standards which sold seven million copies in two years. At 26 he recorded with Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans. Then for 10 years he composed for the Nouvelle Vague directors, while his soundtracks from English-language films stretched from The Go-Between to Never Say Never Again via Portnoy's Complaint. Among his enduring works are musicals made for the screen. Les Parapluies de Cherbourg was an unexpected success in 1964, followed by Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967). He returned to the form in Yentl. Legrand’s Oscar for the score (the film’s only nomination) tells its own story.

Deep into his 70s he composed his first stage musical with Marguerite (2008), updating to occupied Paris the story familiar from La Traviata, Marguerite and Armand and sundry films. Then the Cornish theatre company Kneehigh retrieved The Umbrellas of Cherbourg from the archives. As Legrand’s classic score came alive again for a new audience, he looked back in a long biographical interview.

John Williams conducts Michel Legrand at the Boston Pops

JASPER REES: Do you approach music-making without any regard to genre? You’ve worked in so many different fields.

MICHEL LEGRAND: That makes me more than happy. I’ll tell you why. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (pictured below: Joanna Riding in Kneehigh's stage version) and Yentl, two musicals, it seems to me that it’s impossible to say this is the same composer who made those two things. And people say, “Ja but we hear eight bars of your music and we recognise.” Bullshit. It’s friendly but it’s not true. I cannot eat the same meal every day. I cannot do the same thing every day all the year long. For instance in the Fifties I was an orchestrator and I was pretty famous. I worked with Barbra Streisand, I worked with people in America, in Paris. And then after 10 years of that work or nine years I started to be less interested because I have written so much so I started to be less good. And I said to myself, “OK, now I know I have to stop.”

So I stopped. I said, “No records any more, no nothing, forget me.”So for six months or a year I had no job, no money, no work, nothing. And one year later I was really lucky. There comes in France the New Wave of film directors. They wanted new people, new technicians, new everything. So we were two or three new musicians and I spent 10 years in the Sixties with the film directors, and had a great time. We started to shoot a movie without having any money, without even a producer, not knowing if they were going to pay anyone. I loved it. After 10 years I stated to be less interested, less good, and I thought I have to quit. So I called every director and said, “Forget me, I’m finished.” I called Jean-Luc Godard and said, “Jean-Luc, I don’t want to work, it’s over.” He said, “No no no, I’ve finished a movie, I want you to score it.” I said, “No, Jean-Luc, no, it’s over.” “No no!” I said, “I’ll do it but it’s the last time.”

I flew to America. I had no work, so I rented a house and I waited and then one day I did The Thomas Crown Affair, first Oscar, a big success and after that it was easy for me to work there. And after a certain amount of years, same thing. I had enough. I don’t understand how even a composer for film, how can he devote his whole life. I don’t know how John Williams, whom I love very much... I said, “How can you do the whole of your life the same thing? I have to change, I have to move.” Something that I found a long time ago, when you’re not in danger, your work is not very interesting, because I can search for months if I have time, slowly, nicely, from 9am to 8pm and trying and writing. But when for instance like when I have to do Summer of 42 movie, it was Friday afternoon in Los Angeles. The producer and the director took me to the screening. I said, “I love it, When do you need it? He said, “Wednesday.” I said, “Fine.” Wednesday I recorded it and I was finished by Sunday night. Because when they have no time to do something, a very short time, you come up with something much more extraordinary than if you have searched for two years. That’s what I think.

I flew to America. I had no work, so I rented a house and I waited and then one day I did The Thomas Crown Affair, first Oscar, a big success and after that it was easy for me to work there. And after a certain amount of years, same thing. I had enough. I don’t understand how even a composer for film, how can he devote his whole life. I don’t know how John Williams, whom I love very much... I said, “How can you do the whole of your life the same thing? I have to change, I have to move.” Something that I found a long time ago, when you’re not in danger, your work is not very interesting, because I can search for months if I have time, slowly, nicely, from 9am to 8pm and trying and writing. But when for instance like when I have to do Summer of 42 movie, it was Friday afternoon in Los Angeles. The producer and the director took me to the screening. I said, “I love it, When do you need it? He said, “Wednesday.” I said, “Fine.” Wednesday I recorded it and I was finished by Sunday night. Because when they have no time to do something, a very short time, you come up with something much more extraordinary than if you have searched for two years. That’s what I think.

When you discovered jazz as a student of classical music, what did your professors say?

Nadia Boulanger – she hated it. She fought with me and said, “No no no, this stupid ridiculous music with three chords, don’t talk to me about it, no no, you are a classical musician, Michel.” She was doing some dinner at her home and she liked me very much as her student. She invited for dinner with three people like Paul Valéry, Jean Cocteau – it was extraordinary - so I was in the dark listening. At the end of the dinner she’d say, “One of my students is going to play something for you.” So every time I played jazz, because in front of her guests she couldn’t throw me out.

Did she ever forgive you?

I hope she did. She was Minister of Culture at the government of Monte Carlo with the Prince and when I was very young I did a concert there at the Opera with Gene Kelly and Gene onstage with a girl dancer told the complete story of modern dancing. And I was in the pit with an orchestra and Nadia Boulanger was there that night so she called me up afterwards and said, “OK, I forbid you to play jazz but this time it wasn’t too bad.” She forgave me.

Although you listened to it as a child, was your upbringing in classical music?

Before the war when I was a very young boy my father was a nice instinctive musician, a very gifted guy, but he left my mother when I was three years old. My mother had to go out to work so I was alone at home. My older sister was in school and I was too young to go anywhere and all day long I was bored to death. I hated the world of grown-ups, I hated the world of children because it’s so cruel, so rude, so I stayed at home. Miraculously my father forgot an old piano at home so I spent all my days at the piano. All the time I was listening to the radio. I heard a rhythmic song, so I tried to find the melody on the piano, then I tried to find the harmonies underneath. My only reason for living was this piano.

So my mother was a very bright woman, so seeing that she gave me some teacher and I entered the Conservatory when I was very very young, I was nine years old, much too young. Officially I couldn’t come at nine years old so I had special intervention of my teachers. I did extraordinary work. I have great memories of working at the Conservatory because I hated the world, I refused to go to school, I never went to school, never, but when I entered the conservatory at nine years old that was my planet because the only thing they were doing was music everywhere in this big building. And I said, “That’s my life.”

Did you know it would be your professional life?

No, I knew that my life was music but I didn’t know what.

Did you know how good you were?

Good no but I knew how gifted I was because everything was easy. My colleagues worked one week on something and I could do it in two hours.

How early on did you have melodies pouring out of your fingers?

No. Melody didn’t pour naturally. In the Fifties when I started professionally to write orchestrations, arrangements, for Piaf, for Yves Montand, for everyone, I was not writing songs of melody at all. It started when the film came in 1959, ‘60, when I had to write scores for movies. I always wrote 30 or 40 different things and then I proceeded by elimination day after day until one or two or three resisted until the very end.

Why don’t the French like musicals?

I was very bad towards films. In the Sixties I made a hundred French movies. In the Seventies and Eighties I made a hundred American movies. So I was really concentrated on films. But in 1963 or 1964 I was one of the first persons to see West Side Story onstage, which I loved. French people are not musicians. Not because they are not by instinct, they are like everyone, but there is no musical education at all in France. Art, painting: nothing. Literature: enormous. France is a country of literary people. That’s all. Music: nothing. French audiences know nothing about music so when they see people singing onstage they don’t understand why. It’s exactly what happened. I was extremely surprised and I still don’t know why when we did with Jacques Demy The Umbrellas of Cherbourg in 1964 it was such a success. I swear to you. When we were writing it, everybody was saying, “Jesus Christ, how can you expect people in a dark theatre to stay 90 minutes listening to people singing? Do you feel better today and how is your stomach? It will never work, never.” We couldn’t find the producer to do the film. So everybody said, for weeks and weeks and for months. So we were sure that it was going to be a flop and the first day it was a success. We had no money even to promote it

Barbra Streisand is very temperamental and very demanding so people don’t like it very much

Have you ever wanted to have control of the lyrics, especially in a foreign language?

I don’t have this pretension but I’m very sensitive on lyrics, so very often I said to lyricists, “I’m not sure this is exactly right.” But I’ve never wanted to have control. Especially with the Bergmans, my American lyricists who are really extraordinary [Alan and Marilyn Bergman wrote the lyrics for “The Windmills of My Mind” and Yentl]. I was really ecstatic about their work. I chose to work with extraordinary lyricists of course.

Did you know what they mean by “Windmills of My Mind”?

Yeah, because I asked them. With [Norman] Jewison we decided to have a song. I said to Norman, “Why don’t we have a song when they’re on the glider? “So I called the Bergmans. I said, “I would love to have something which moves all around, like an airplane.” The windmills of my mind, I love that idea very much.

"Windmills of My Mind" from The Thomas Crown Affair

How often do you write to words?

I did it. I prefer to write the music first of course. But it happened to me for instance in Yentl. We had nine songs in it, I think three of the songs come from the lyrics first.

Why is that film not loved?

It is very well done, I liked it very much. But it’s funny because Barbra Streisand, her colleagues, she’s not liked over there. So for instance when the film appeared to be nominated for the Oscars, not one nomination. Just one, for the score. And that’s not nice because she deserves more than that, better than that. But she is very temperamental and very demanding so people don’t like it very much.

Barbra Streisand sings "Papa Can You Hear Me?" from Yentl

Are you able to cope with that?

Very easily. She’s a 12-year-old little girl. I have to tell you, because we have done so many things together – records and piano and afternoons singing – she knows me so well, she knows that I can get her to do anything just like this, so she trusts me, she has confidence, so life is very simple. We are like two kids playing the same game. And she is so sweet and lovely. For instance, one little anecdote. During the recording of Yentl, one session we had 120 musicians, four pianos, eight guitars, symphony orchestra. And we recorded the first take, marvellous, and then Barbra came to me and said, “Michel, I would love to try it half a tone lower because today I feel a little tired.” So she said, “Have it re-copied and we’ll do it tomorrow.” I said, “No, we’re going to do it now.” She said, “It’s impossible.” I said, “Yes, we will right now.” So she goes back to the booth and I didn’t know how to tell the musicians how to transpose, because half a tone is the worst. So I said, “OK guys, it was beautiful, do exactly as well as you did before, with just one tiny little change, three, four!” They had no time to react. And they did it. Pretty well. She was amazed at what they did. For her it’s magic but for us it’s simple.

It’s quicker to list the people you have not worked with. Has there ever been a time when you have not liked working with someone?

Interview continued overleaf

“I want to be a man without any past,” said Michel Legrand, who has died at the age of 86. He had perhaps the longest past in showbiz. Orchestrator, pianist, conductor, composer of countless soundtracks, who else has collaborated as widely - with Miles Davis and Kiri Te Kanawa, Barbra Streisand and Jean-Luc Godard, Gene Kelly, Joseph Losey and Edith Piaf? When I visited him at his house at his splendid classical manoir 100km south of Paris, on the mantelpiece in the large white sitting room four familiar gilt statuettes stood sentry. The oldest was for “Windmills of My Mind”, the best original song of 1965.

A child prodigy at the piano, he converted from classical to jazz under the nose of his disapproving teacher, the composer Nadia Boulanger. Initially he worked as an orchestrator; his earliest triumph was I Love Paris, a set of jazz standards which sold seven million copies in two years. At 26 he recorded with Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans. Then for 10 years he composed for the Nouvelle Vague directors, while his soundtracks from English-language films stretched from The Go-Between to Never Say Never Again via Portnoy's Complaint. Among his enduring works are musicals made for the screen. Les Parapluies de Cherbourg was an unexpected success in 1964, followed by Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967). He returned to the form in Yentl. Legrand’s Oscar for the score (the film’s only nomination) tells its own story.

Deep into his 70s he composed his first stage musical with Marguerite (2008), updating to occupied Paris the story familiar from La Traviata, Marguerite and Armand and sundry films. Then the Cornish theatre company Kneehigh retrieved The Umbrellas of Cherbourg from the archives. As Legrand’s classic score came alive again for a new audience, he looked back in a long biographical interview.

John Williams conducts Michel Legrand at the Boston Pops

JASPER REES: Do you approach music-making without any regard to genre? You’ve worked in so many different fields.

MICHEL LEGRAND: That makes me more than happy. I’ll tell you why. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (pictured below: Joanna Riding in Kneehigh's stage version) and Yentl, two musicals, it seems to me that it’s impossible to say this is the same composer who made those two things. And people say, “Ja but we hear eight bars of your music and we recognise.” Bullshit. It’s friendly but it’s not true. I cannot eat the same meal every day. I cannot do the same thing every day all the year long. For instance in the Fifties I was an orchestrator and I was pretty famous. I worked with Barbra Streisand, I worked with people in America, in Paris. And then after 10 years of that work or nine years I started to be less interested because I have written so much so I started to be less good. And I said to myself, “OK, now I know I have to stop.”

So I stopped. I said, “No records any more, no nothing, forget me.”So for six months or a year I had no job, no money, no work, nothing. And one year later I was really lucky. There comes in France the New Wave of film directors. They wanted new people, new technicians, new everything. So we were two or three new musicians and I spent 10 years in the Sixties with the film directors, and had a great time. We started to shoot a movie without having any money, without even a producer, not knowing if they were going to pay anyone. I loved it. After 10 years I stated to be less interested, less good, and I thought I have to quit. So I called every director and said, “Forget me, I’m finished.” I called Jean-Luc Godard and said, “Jean-Luc, I don’t want to work, it’s over.” He said, “No no no, I’ve finished a movie, I want you to score it.” I said, “No, Jean-Luc, no, it’s over.” “No no!” I said, “I’ll do it but it’s the last time.”

I flew to America. I had no work, so I rented a house and I waited and then one day I did The Thomas Crown Affair, first Oscar, a big success and after that it was easy for me to work there. And after a certain amount of years, same thing. I had enough. I don’t understand how even a composer for film, how can he devote his whole life. I don’t know how John Williams, whom I love very much... I said, “How can you do the whole of your life the same thing? I have to change, I have to move.” Something that I found a long time ago, when you’re not in danger, your work is not very interesting, because I can search for months if I have time, slowly, nicely, from 9am to 8pm and trying and writing. But when for instance like when I have to do Summer of 42 movie, it was Friday afternoon in Los Angeles. The producer and the director took me to the screening. I said, “I love it, When do you need it? He said, “Wednesday.” I said, “Fine.” Wednesday I recorded it and I was finished by Sunday night. Because when they have no time to do something, a very short time, you come up with something much more extraordinary than if you have searched for two years. That’s what I think.

I flew to America. I had no work, so I rented a house and I waited and then one day I did The Thomas Crown Affair, first Oscar, a big success and after that it was easy for me to work there. And after a certain amount of years, same thing. I had enough. I don’t understand how even a composer for film, how can he devote his whole life. I don’t know how John Williams, whom I love very much... I said, “How can you do the whole of your life the same thing? I have to change, I have to move.” Something that I found a long time ago, when you’re not in danger, your work is not very interesting, because I can search for months if I have time, slowly, nicely, from 9am to 8pm and trying and writing. But when for instance like when I have to do Summer of 42 movie, it was Friday afternoon in Los Angeles. The producer and the director took me to the screening. I said, “I love it, When do you need it? He said, “Wednesday.” I said, “Fine.” Wednesday I recorded it and I was finished by Sunday night. Because when they have no time to do something, a very short time, you come up with something much more extraordinary than if you have searched for two years. That’s what I think.

When you discovered jazz as a student of classical music, what did your professors say?

Nadia Boulanger – she hated it. She fought with me and said, “No no no, this stupid ridiculous music with three chords, don’t talk to me about it, no no, you are a classical musician, Michel.” She was doing some dinner at her home and she liked me very much as her student. She invited for dinner with three people like Paul Valéry, Jean Cocteau – it was extraordinary - so I was in the dark listening. At the end of the dinner she’d say, “One of my students is going to play something for you.” So every time I played jazz, because in front of her guests she couldn’t throw me out.

Did she ever forgive you?

I hope she did. She was Minister of Culture at the government of Monte Carlo with the Prince and when I was very young I did a concert there at the Opera with Gene Kelly and Gene onstage with a girl dancer told the complete story of modern dancing. And I was in the pit with an orchestra and Nadia Boulanger was there that night so she called me up afterwards and said, “OK, I forbid you to play jazz but this time it wasn’t too bad.” She forgave me.

Although you listened to it as a child, was your upbringing in classical music?

Before the war when I was a very young boy my father was a nice instinctive musician, a very gifted guy, but he left my mother when I was three years old. My mother had to go out to work so I was alone at home. My older sister was in school and I was too young to go anywhere and all day long I was bored to death. I hated the world of grown-ups, I hated the world of children because it’s so cruel, so rude, so I stayed at home. Miraculously my father forgot an old piano at home so I spent all my days at the piano. All the time I was listening to the radio. I heard a rhythmic song, so I tried to find the melody on the piano, then I tried to find the harmonies underneath. My only reason for living was this piano.

So my mother was a very bright woman, so seeing that she gave me some teacher and I entered the Conservatory when I was very very young, I was nine years old, much too young. Officially I couldn’t come at nine years old so I had special intervention of my teachers. I did extraordinary work. I have great memories of working at the Conservatory because I hated the world, I refused to go to school, I never went to school, never, but when I entered the conservatory at nine years old that was my planet because the only thing they were doing was music everywhere in this big building. And I said, “That’s my life.”

Did you know it would be your professional life?

No, I knew that my life was music but I didn’t know what.

Did you know how good you were?

Good no but I knew how gifted I was because everything was easy. My colleagues worked one week on something and I could do it in two hours.

How early on did you have melodies pouring out of your fingers?

No. Melody didn’t pour naturally. In the Fifties when I started professionally to write orchestrations, arrangements, for Piaf, for Yves Montand, for everyone, I was not writing songs of melody at all. It started when the film came in 1959, ‘60, when I had to write scores for movies. I always wrote 30 or 40 different things and then I proceeded by elimination day after day until one or two or three resisted until the very end.

Why don’t the French like musicals?

I was very bad towards films. In the Sixties I made a hundred French movies. In the Seventies and Eighties I made a hundred American movies. So I was really concentrated on films. But in 1963 or 1964 I was one of the first persons to see West Side Story onstage, which I loved. French people are not musicians. Not because they are not by instinct, they are like everyone, but there is no musical education at all in France. Art, painting: nothing. Literature: enormous. France is a country of literary people. That’s all. Music: nothing. French audiences know nothing about music so when they see people singing onstage they don’t understand why. It’s exactly what happened. I was extremely surprised and I still don’t know why when we did with Jacques Demy The Umbrellas of Cherbourg in 1964 it was such a success. I swear to you. When we were writing it, everybody was saying, “Jesus Christ, how can you expect people in a dark theatre to stay 90 minutes listening to people singing? Do you feel better today and how is your stomach? It will never work, never.” We couldn’t find the producer to do the film. So everybody said, for weeks and weeks and for months. So we were sure that it was going to be a flop and the first day it was a success. We had no money even to promote it

Barbra Streisand is very temperamental and very demanding so people don’t like it very much

Have you ever wanted to have control of the lyrics, especially in a foreign language?

I don’t have this pretension but I’m very sensitive on lyrics, so very often I said to lyricists, “I’m not sure this is exactly right.” But I’ve never wanted to have control. Especially with the Bergmans, my American lyricists who are really extraordinary [Alan and Marilyn Bergman wrote the lyrics for “The Windmills of My Mind” and Yentl]. I was really ecstatic about their work. I chose to work with extraordinary lyricists of course.

Did you know what they mean by “Windmills of My Mind”?

Yeah, because I asked them. With [Norman] Jewison we decided to have a song. I said to Norman, “Why don’t we have a song when they’re on the glider? “So I called the Bergmans. I said, “I would love to have something which moves all around, like an airplane.” The windmills of my mind, I love that idea very much.

"Windmills of My Mind" from The Thomas Crown Affair

How often do you write to words?

I did it. I prefer to write the music first of course. But it happened to me for instance in Yentl. We had nine songs in it, I think three of the songs come from the lyrics first.

Why is that film not loved?

It is very well done, I liked it very much. But it’s funny because Barbra Streisand, her colleagues, she’s not liked over there. So for instance when the film appeared to be nominated for the Oscars, not one nomination. Just one, for the score. And that’s not nice because she deserves more than that, better than that. But she is very temperamental and very demanding so people don’t like it very much.

Barbra Streisand sings "Papa Can You Hear Me?" from Yentl

Are you able to cope with that?

Very easily. She’s a 12-year-old little girl. I have to tell you, because we have done so many things together – records and piano and afternoons singing – she knows me so well, she knows that I can get her to do anything just like this, so she trusts me, she has confidence, so life is very simple. We are like two kids playing the same game. And she is so sweet and lovely. For instance, one little anecdote. During the recording of Yentl, one session we had 120 musicians, four pianos, eight guitars, symphony orchestra. And we recorded the first take, marvellous, and then Barbra came to me and said, “Michel, I would love to try it half a tone lower because today I feel a little tired.” So she said, “Have it re-copied and we’ll do it tomorrow.” I said, “No, we’re going to do it now.” She said, “It’s impossible.” I said, “Yes, we will right now.” So she goes back to the booth and I didn’t know how to tell the musicians how to transpose, because half a tone is the worst. So I said, “OK guys, it was beautiful, do exactly as well as you did before, with just one tiny little change, three, four!” They had no time to react. And they did it. Pretty well. She was amazed at what they did. For her it’s magic but for us it’s simple.

It’s quicker to list the people you have not worked with. Has there ever been a time when you have not liked working with someone?

Interview continued overleaf

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...