The Blue Dragon, Barbican Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

The Blue Dragon, Barbican Theatre

The Blue Dragon, Barbican Theatre

Robert Lepage's stunning collision between East and West

Saturday, 19 February 2011

Forked lightning glimpsed through an aeroplane window, a silken dancer spilling stars in a snow-filled sky, a dragon tattoo etched on a man’s back: we’ve grown to expect seductive alchemy of images from the work of Quebecois master of visual theatre Robert Lepage, and in his latest show he doesn’t disappoint.

For all that, The Blue Dragon – which picks up the action of director, writer and actor Lepage’s Eighties breakthrough The Dragons' Trilogy 25 years on, and is co-written with a collaborator on that piece, Marie Michaud – is a comparatively distilled piece for a theatre-maker who typically gives us dizzying multi-strand narratives and a riot of technical wizardry. Yet it is exquisite, and quietly profound: a gorgeous and poignant series of oppositions between East and West, ancient and modern, solitude and connection.

'As usual, Lepage wears his politics lightly, focusing instead on the personal'

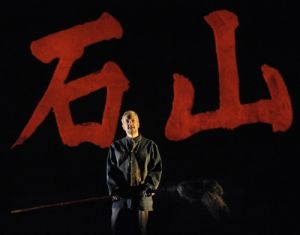

Chinese calligraphy – the writing of language that depicts what it expresses, in its shape on the page as much as in its meaning – runs as a theme through the drama, and is symbolic of the frequent paucity of spoken eloquence to convey true feelings and desires. Fiftysomething Pierre Lamontagne (Lepage himself, pictured right), who in The Dragons’ Trilogy declared his intention to go to China, has here been true to his word, and has opened an art gallery in Shanghai. His own name – which translates from French as Stone Mountain – makes him feel an inadequate successor to his father, a mere pebble to his mighty peak. A foreigner in a country he scarcely understands, and threatened with expropriation in a burgeoning city and ruthlessly expanding economy, the last thing Pierre needs is a visit from his ex-wife, Claire (Michaud), who has come to China in the hope of adopting a child – particularly when he’s about to mount an exhibition of work by his young Chinese lover, Xiao Ling (Tai Wei Foo). Like China, and like the Yangtze River which divides into three, and where, traditionally, desperate women cast away unplanned babies to meet their fate, Pierre, confronting late middle age, faces a parting of the ways of his destiny, and a challenging choice about how to live the rest of his life.

Chinese calligraphy – the writing of language that depicts what it expresses, in its shape on the page as much as in its meaning – runs as a theme through the drama, and is symbolic of the frequent paucity of spoken eloquence to convey true feelings and desires. Fiftysomething Pierre Lamontagne (Lepage himself, pictured right), who in The Dragons’ Trilogy declared his intention to go to China, has here been true to his word, and has opened an art gallery in Shanghai. His own name – which translates from French as Stone Mountain – makes him feel an inadequate successor to his father, a mere pebble to his mighty peak. A foreigner in a country he scarcely understands, and threatened with expropriation in a burgeoning city and ruthlessly expanding economy, the last thing Pierre needs is a visit from his ex-wife, Claire (Michaud), who has come to China in the hope of adopting a child – particularly when he’s about to mount an exhibition of work by his young Chinese lover, Xiao Ling (Tai Wei Foo). Like China, and like the Yangtze River which divides into three, and where, traditionally, desperate women cast away unplanned babies to meet their fate, Pierre, confronting late middle age, faces a parting of the ways of his destiny, and a challenging choice about how to live the rest of his life.Ideas proliferate: ageing, artistic and personal freedom, China’s ravenous consumerist present and its communist history, the uncomfortable bedfellows of exploitation and altruism in the act of adoption by wealthy Westerners from a country with a strict one-child policy. But, as usual, Lepage wears the politics lightly and focuses on the personal: Pierre is caught between two women, and between home in Canada and the place he has come to love, yet which seems so eager to spit him back out. A particularly piercing sequence sees Pierre recall his meeting with Xiao Ling in a Hong Kong tattoo parlour; the ink on his skin is, he says, “the map of one’s pains and pleasures”. Another sees him make two fatal strokes of his calligraphy brush, magnified on a screen, and echoed in the two lines that appear on Xiao Ling’s pregnancy test.

The production is both simple in its immediacy and complex in its technical achievement, the symbols never overworked, the acting unfussy and truthful, the text translucent. Those captivated by the more jaw-dropping spectacle in Lepage’s previous work, or expecting the hectic multi-strand narratives he’s employed in the past, might be deflated by the more meditative tone here. But he is a master of the theatrical moment, poised in an instant of perfect synthesis of meaning, emotion and sensual ravishment.

- The Blue Dragon at the Barbican Theatre until 26 February

- Read theartsdesk Q&A with Robert Lepage

- See what's on at the Barbican Centre. Read Barbican reviews.

Find Robert Lepage on Amazon

Find Robert Lepage on Amazon

Share this article

more Theatre

Testmatch, The Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Testmatch, The Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Add comment