Inside Job | reviews, news & interviews

Inside Job

Inside Job

You'll want your money back: the credit crunch story told yet again

Inside Inside Job is an interesting film struggling to get out. Sadly, one has to sit through two hours of Financial Meltdown 101 to see it. Narrated by Matt Damon in his serious voice (and if you're anything like me, you'll always be thinking of his Team America caricature), the film starts with the perfect glaciers of Iceland being ravaged as the free market takes its toll.

These first five minutes tell us that director and producer Charles Ferguson conceives of this enterprise on a grand scale, as some definitive cinematic essay, rather than the choppy left-wing polemic it is. The film is, in fact, as arrogant as the system it portrays, having Damon declaim the need to get rid of the heads of the big banks, ending on a shot of the Statue of Liberty.

There are plenty of authoritative talking heads - Dr Doom himself, Nouriel Roubini; Dominique Strauss-Kahn of the International Monetary Fund; and Christine Lagarde, the French finance minister who looks like she's having a hard time not gloating about the disaster of Anglo-Saxon capitalism. When this is your jury, can we be surprised about the verdict they reach?

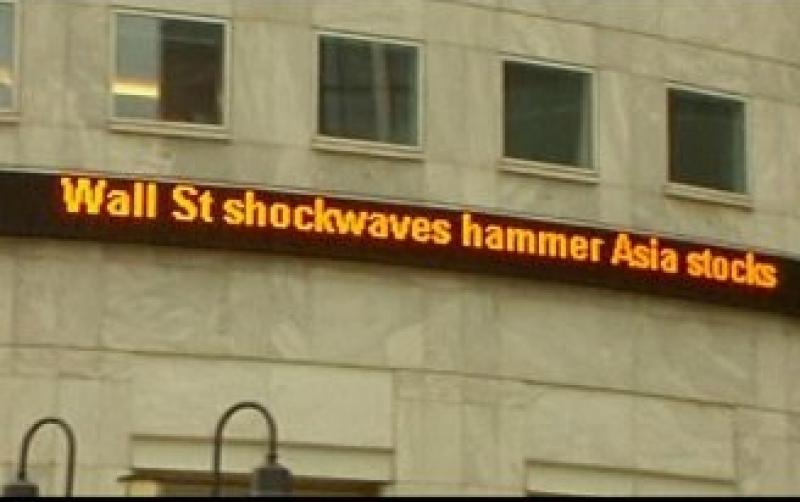

Be in no doubt: this film finds the entire financial services sector guilty. Bankers loaned too much to people who could never repay it, then chopped up these subprime mortgages and sold them to credulous, greedy investors. Credit-ratings agencies burnished these securities with AAA ratings. The US political system is greased by bankers, who also - coincidentally - inhabit positions of power within both the Democrat and Republican administrations.

Watch the trailer to Inside Job

None of these things is wrong - they are just simplistic. There was no obligation for Americans to borrow money they couldn't repay - what happened to personal responsibility? Why doesn't the film examine the culture that says you must own your own home? Americans have long lived beyond their means, but no mention is made of greed. As for bankers in government, when they are the only people who understand the financial system, it's better to co-opt them and their knowledge than exclude them and stare blankly at a Bloomberg terminal.

Senior bankers refused to make themselves available, and while silence can seem as incriminating as speech, it means there are few people to put any sort of case for the banks. (The talking head from the banks' lobbying group ought to have taken the Fifth.) Even if you find the idea of the bankers having a defence laughable, there are questions which go unasked: it would be far more valuable to learn why they thought their securitised products were risk-free or whether they felt guilty (and to be honest, those I know don't) than to tar and feather them. (Pictured below, three guilty men: Bush treasury secretary Hank Paulson, governor of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke, Obama's treasury secretary Tim Geithner.)

We have lived through three years of tarring and feathering anyway, so why is there a need for this film now? The answer is that there isn't really, for anyone who's been paying attention to the newspapers or internet since Lehmans went down. This film won't appeal to a general audience, and those who will go to see it know all of this already. Britain has already been lavishly served by documentaries on the financial crisis: Robert Peston's was half as long and had many more influential interviewees - on both sides of the question. The Power of Yes at the National, while thoroughly undramatic, was a vivid lecture with greater complexity.

We have lived through three years of tarring and feathering anyway, so why is there a need for this film now? The answer is that there isn't really, for anyone who's been paying attention to the newspapers or internet since Lehmans went down. This film won't appeal to a general audience, and those who will go to see it know all of this already. Britain has already been lavishly served by documentaries on the financial crisis: Robert Peston's was half as long and had many more influential interviewees - on both sides of the question. The Power of Yes at the National, while thoroughly undramatic, was a vivid lecture with greater complexity.

It ignores one crucial question, too: why did the crisis actually occur? We are shown the kindling - the mortgages, the securities - and the conflagration but are never told what sparked Lehmans' fall. The complexity of this issue, which is key to understanding the true nature of our highly global interconnected financial system, is not examined at all. Far better to read Andrew Ross Sorkin's superb Too Big to Fail if you want the truth in excruciating detail. For that matter, there are barely any mentions of foreign banks: what about the European precursors to the crisis? The film is US-centric, which betrays a lack of either interest or comprehension.

So what is this interesting film hiding within Inside Job? Its fourth section is about how university economics departments have been captured by professors who have taken money from banks for legitimate consulting or other projects. Allegations are made that this causes a conflict of interests, that when they teach pro-market, anti-regulation orthodoxies, they are doing so not just because they believe it but because their bank accounts demand it. And when Ferguson confronts economics professors with charges of vested interests, he gets plenty of shifting in chairs.

Here he hits a nerve and exposes something important, and this would make a fascinating documentary on its own; the rest of the film is a papier-mâché model made from yesterday's newspapers.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Friendship review - toxic buddy alert

Dark comedy stars Tim Robinson as a social misfit with cringe benefits

Friendship review - toxic buddy alert

Dark comedy stars Tim Robinson as a social misfit with cringe benefits

S/HE IS STILL HER/E - The Official Genesis P-Orridge Documentary review - a shapeshifting open window onto a counter-cultural radical

Intimate portrait of the Throbbing Gristle & Psychic TV antagonist

S/HE IS STILL HER/E - The Official Genesis P-Orridge Documentary review - a shapeshifting open window onto a counter-cultural radical

Intimate portrait of the Throbbing Gristle & Psychic TV antagonist

Blu-ray: Heart of Stone

Deliciously dark fairy tale from post-war Eastern Europe

Blu-ray: Heart of Stone

Deliciously dark fairy tale from post-war Eastern Europe

Superman review - America's ultimate immigrant

James Gunn's over-stuffed reboot stutters towards wonder

Superman review - America's ultimate immigrant

James Gunn's over-stuffed reboot stutters towards wonder

The Other Way Around review - teasing Spanish study of a breakup with unexpected depth

Jonás Trueba's film holds the romcom up to the light for playful scrutiny

The Other Way Around review - teasing Spanish study of a breakup with unexpected depth

Jonás Trueba's film holds the romcom up to the light for playful scrutiny

The Road to Patagonia review - journey to the end of the world

In search of love and the meaning of life on the boho surf trail

The Road to Patagonia review - journey to the end of the world

In search of love and the meaning of life on the boho surf trail

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Emma Mackey on 'Hot Milk' and life education

The Anglo-French star of 'Sex Education' talks about her new film’s turbulent mother-daughter bind

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Emma Mackey on 'Hot Milk' and life education

The Anglo-French star of 'Sex Education' talks about her new film’s turbulent mother-daughter bind

Blu-ray: A Hard Day's Night

The 'Citizen Kane' of jukebox musicals? Richard Lester's film captures Beatlemania in full flight

Blu-ray: A Hard Day's Night

The 'Citizen Kane' of jukebox musicals? Richard Lester's film captures Beatlemania in full flight

Hot Milk review - a mother of a problem

Emma Mackey shines as a daughter drawn to the deep end of a family trauma

Hot Milk review - a mother of a problem

Emma Mackey shines as a daughter drawn to the deep end of a family trauma

The Shrouds review - he wouldn't let it lie

More from the gruesome internal affairs department of David Cronenberg

The Shrouds review - he wouldn't let it lie

More from the gruesome internal affairs department of David Cronenberg

Jurassic World Rebirth review - prehistoric franchise gets a new lease of life

Scarlett Johansson shines in roller-coaster dino-romp

Jurassic World Rebirth review - prehistoric franchise gets a new lease of life

Scarlett Johansson shines in roller-coaster dino-romp

Comments

...