John Lennon's Love and Death: 30 Years On, Part 1 | reviews, news & interviews

John Lennon's Love and Death: 30 Years On, Part 1

John Lennon's Love and Death: 30 Years On, Part 1

A portrait of The Beatles' end and of Lennon just before he died

The couples profiled in the series included the likes of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald, Sartre and de Beauvoir, Monroe and Miller, and remoter figures from the German 19th century. Pop hadn’t made it onto the list, though I learnt, once embarked on the commission, that Lennon-Ono had been considered but no author found. In 1996, I happened to be in the right place (Berlin) at the right time.

John Lennon und Yoko Ono - zwei Rebellen, eine Poplegende (the last four words mean “two rebels, one pop legend”: the publisher's, not my, subtitle) went on to be one of the series’ bestselling books. My research included essential information from one interviewee who remembered exactly how and when John and Yoko met, and another who helped explain the nature of their struggles with drugs and their domestic chaos in the early 1970s - amongst other details which have rarely made it into the conventional (and, if Ono-approved, fatally sanitised) accounts of their 14 years together.

The book never appeared in English, owing to a saturation of Beatles books in the 1990s. The anniversary of Lennon’s death, marked by an eloquent ITV film on Monday, 6 December, The Day John Lennon Died, prompts these edited extracts.

At 20, I thought it weak-minded - even silly - to mourn John’s death. I was wrong. The writing of this book in my mid-30s was, largely, an attempt to correct that.

Remembering

At the age of 10, the only person I’d rather have been than myself was John Lennon. He was the epitomé of manliness and cool - and unquestionably head of The Beatles. I’d have been happy to be any Beatle at all, but somehow John had the edge. For a belated Beatlemaniac like me, born in 1960, John came to be almost a father-figure, to the dismay of my real father, whose principal objections to this hairy pop star was that he’d insulted the Queen - by returning his MBE in 1969 - and took too many drugs.

My mother liked The Beatles, but she too found the John Lennon I adored hard to figure out. One morning during the school holidays, some time in 1972, when John’s crazy “Revolution 9” from the “White Album” was blaring out of the old single-unit stereo player in the playroom, she stormed in and crossly asked me what on earth made me think “that” was “music”. The loopy cascade of sound indeed meant little to me then. Turning my attentions to John Lennon over 25 years later led to a far clearer understanding of what he was trying to do, there and on other tracks where he was overtly inspired by - and working with - Yoko Ono.

My father, meanwhile, was not a Beatles fan. When Yoko Ono asked the world to remain silent for 10 minutes in December 1980 in honour of her murdered husband, Dad pointed out that five times the amount of silence observed each November in Britain for the fallen of two World Wars was being asked for. There was certainly one reason why he might think John’s widow, at least, ridiculous. In 1967, she made a film of 365 bottoms (forever known as Yoko’s Bottoms); Dad’s rebellious elder brother Corbet, about to become a well-known face alongside Michael Aspel as a BBC newsreader, had bared his own bum for this cheeky celluloid adventure.

Amidst the grieving of late 1980 (pictured right), much of it admittedly hyped and soft-centred, Dad was taking a reasonable, if perilously old-fashioned, line, not least of all with his erstwhile Beatles-besotted eldest son. It was to be expected. My father would be the first to concede that he belonged to a generation which regarded the hedonism of the 1960s with bemusement and fatigue; he’d all but ignored it anyway when it was happening. In 1980, I was old enough to accept that even if he was disarmed by John’s murder, he wasn’t going to go into prolonged mourning over it. To his objection about Yoko’s unquestionably bold request, I merely replied that she was asking for 10 minutes just once, while Poppy Day happens every year.

Amidst the grieving of late 1980 (pictured right), much of it admittedly hyped and soft-centred, Dad was taking a reasonable, if perilously old-fashioned, line, not least of all with his erstwhile Beatles-besotted eldest son. It was to be expected. My father would be the first to concede that he belonged to a generation which regarded the hedonism of the 1960s with bemusement and fatigue; he’d all but ignored it anyway when it was happening. In 1980, I was old enough to accept that even if he was disarmed by John’s murder, he wasn’t going to go into prolonged mourning over it. To his objection about Yoko’s unquestionably bold request, I merely replied that she was asking for 10 minutes just once, while Poppy Day happens every year.

This exchange between father and son still says something about John Lennon, The Beatles and the generations they divided. With the group’s emergence in the early 1960s (just as my father had begun his fourth decade), a revolutionary era loomed. Rock’n’roll had happened; Elvis Presley was a fact of life. American popular culture might have looked lurid from this side of the Atlantic, but as long as it stayed “over there”, good old Britain could probably hold its own - victors (with the Americans) in 1945, 10 years later agreeably literary at the top of the arts tree (Angry Young Men notwithstanding) and pleasantly jolly at a lower-brow level (music hall and sweet crooning, along with Flanders and Swann, still reigned supreme in the 1950s).

Yet by 1960, the old certainties in Britain, of empire, authority and deference, above all of class, were crumbling; the Angry Young Men - John Osborne their doyen - had begun to reflect it. Soon, the zest, freshness, and absence of inhibition and of politesse exemplified by the early Beatles (soon to be steered in a more sneering direction by The Rolling Stones) awakened things the British establishment greatly feared: a triumph of youth over experience, sex over propriety, an end of respect and, most threateningly, the breaking of class barriers - all part and parcel of the same trajectory from post-war consensus to polyvalent, peace-time individualism.

No-one who was there will forget that in the year The Beatles became Britain’s unofficial leaders - 1963 (Harold Macmillan was actually Prime Minister) - an upper-class war minister, John Profumo, was forced to resign from Her Majesty’s Government after deceiving Parliament over his liaison with callgirl Christine Keeler. Sex was in the open air, and it wasn’t only The Beatles’ (and The Stones’) doing.

Commenting on the press’s response to this pop phenomenon, Philip Norman, one of The Beatles’ better biographers, wrote (in Shout!, from 1980): "The papers sensed their readership to be sated with the dingy adventures of John Profumo, Christine Keeler and the tottering Macmillan government. But the mania, once noticed, proved bigger than any front page. A whole generation, left intact by 20 years’ peace, unstiffened by National Service, with fortunes to fritter on its youthful pleasure, established the unsteady decade in one great, shivering scream for John, Paul, George and Ringo."

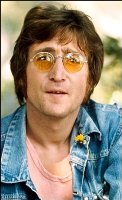

The British establishment also enjoyed its own version of Beatlemania for a few years. The group brought fat wads of dosh to the Treasury, after all (as George Harrison noted with his zinging opener to 1966's Revolver, "Taxman": (pictured left: John at the time of Revolver). The establishment bestowed its highest honour on the four in 1965 when, advised by Harold Wilson, the Queen awarded them the MBE. Testy ex-colonels returned their medals in protest. Within a year, The Beatles were transformed: no longer touring, they were growing their hair and experimenting with strange sounds in the studio, and with equally strange drugs - or, overwhelmingly, John was.

The British establishment also enjoyed its own version of Beatlemania for a few years. The group brought fat wads of dosh to the Treasury, after all (as George Harrison noted with his zinging opener to 1966's Revolver, "Taxman": (pictured left: John at the time of Revolver). The establishment bestowed its highest honour on the four in 1965 when, advised by Harold Wilson, the Queen awarded them the MBE. Testy ex-colonels returned their medals in protest. Within a year, The Beatles were transformed: no longer touring, they were growing their hair and experimenting with strange sounds in the studio, and with equally strange drugs - or, overwhelmingly, John was.

Just before this, John had made his first major PR error: “We’re more popular than Jesus now” were the words Maureen Cleave, his interviewer for the Evening Standard in March 1966, had him saying: “I don't know which will go first - rock’n’roll or Christianity. Jesus was alright, but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

The comment, brilliantly - and typically - flippant, brought the group face to face with their first taste of massive public opprobrium; and it hailed down on them from the United States, The Beatles’ most lucrative market. Though John publicly “apologised” there, some point to this episode as the end, for John, of The Beatles. The claim goes that he never really recovered from the battering. There’s some truth in this.

Equally, John was without doubt looking for a way out of “being a Beatle” - not out of the group, exactly, as the other three still provided an artistic lifeline for him. He was nonetheless bored of the cuddly Mop Top image. His jagged restlessness was driving him headlong into controversy; controversy was in his nature and always had been. The Jesus gaffe was loud public evidence that The Beatles had a real troublemaker in their midst, which of course the immediate Beatles entourage had known for years. For those who hadn’t quite known (Beatles lovers everywhere), John Lennon’s transformation after 1966 was one of the most bewildering processes of that transforming time.

The mid-1990s saw (unless you’re too old, or perhaps too young, for The Beatles to matter) an extraordinary revival of public interest in Britain’s first super-group. Television documentaries, newspaper articles, the issuing of three CD volumes of studio outtakes, a new single in late 1995 (“Free as a Bird”, with John’s ghostly voice resurrected from a 1977 cassette) and another in 1996 (“Real Love”, based on another sketch of John’s), and, by then, dozens of books might prompt a disinterested observer into thinking The Beatles were then still Britain’s - the world’s - most contemporary pop group.

In a way, they were and are. It was almost inconceivable (but not impossible) for anyone under 60 to be disinterested; the Beatles story had become part of Britain’s mythology and, in the world, as familiar a post-war tale as the achievements of Mahatma Gandhi, Muhammed Ali and Marlon Brando. At a time when so many news stories were loaded with violence and failure - so many still are - the dizzying success of The Beatles was still something to marvel at. Their heyday has come to be viewed as Britain at its most winning. Recalling it in 1994’s Revolution in the Head, the often dry Ian MacDonald (until his suicide in 2003, one of the finest Beatles chroniclers) was little short of rhapsodic:

"Anyone unlucky enough not to have been aged between 14 and 30 during 1966-7 will never know the excitement of those years in popular culture. A sunny optimism permeated everything and possibilities seemed limitless. Bestriding a British scene that embraced music, poetry, fashion, and film, The Beatles were at their peak and were looked up to in awe as arbiters of a positive new age in which the dead customs of the older generation would be refreshed and remade through the creative energy of the classless young."

The Beatles were different and remain different, a band who, in that burning 1966-7 period (pictured right), possessed a defiant confidence to move on, to somewhere very far from where they’d started. Paul, George and Ringo could each enjoy a sense of artistic certainty rarely available to men in their mid-twenties. Paul in particular, still then only 24, was open to a gamut of cultural impulses which more than partly explains the astonishing strides The Beatles made in the next thee years.

The Beatles were different and remain different, a band who, in that burning 1966-7 period (pictured right), possessed a defiant confidence to move on, to somewhere very far from where they’d started. Paul, George and Ringo could each enjoy a sense of artistic certainty rarely available to men in their mid-twenties. Paul in particular, still then only 24, was open to a gamut of cultural impulses which more than partly explains the astonishing strides The Beatles made in the next thee years.

John was trickier. Less content, more viscerally insecure, he was always looking for personal change. His meeting with an iconoclastic Japanese artist seven years his senior at the end of 1966 was key to this need for change and central to the image we now have of the late 1960s. Post-Sgt. Pepper, post-“White Album”, “John and Yoko” became almost as public and commented-upon a phenomenon as the band itself.

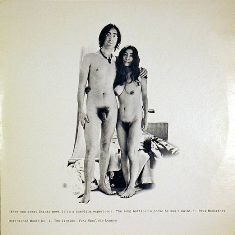

For Yoko Ono, it was a rough ride. From 1968, she became one of the least liked women in the western world. A stranger, an Oriental, had landed in The Beatles’ midst and was apparently taking one of them away. A little of the heat was taken off her and transferred to Linda Eastman when Paul McCartney married the American photographer in March 1969, and deprived every female fan’s fantasy of its last unattached Beatle. Still, the barely concealed contempt which greeted Yoko’s association with John became a sort of national pastime, particularly when the couple was busted for drugs in October 1968 and then, endlessly, after The Beatles broke up in 1970. Yoko was suspect from the start. Who was she? A witch, ran one theory, who waited for John to cut his fingernails so that she could come and pick up the clippings, and put a curse on him. An upstart New York avant-gardist descending on Swinging London to steal away a national treasure. A small, birdlike creature with pendulous breasts (clear, in late 1968 - to anyone who could be bothered to look - on the cover of her and John’s record Two Virgins: pictured left), who spoke weird English, couldn’t sing and when she did open her mouth spouted hippie mantras. What on earth had happened to John?

Yoko was suspect from the start. Who was she? A witch, ran one theory, who waited for John to cut his fingernails so that she could come and pick up the clippings, and put a curse on him. An upstart New York avant-gardist descending on Swinging London to steal away a national treasure. A small, birdlike creature with pendulous breasts (clear, in late 1968 - to anyone who could be bothered to look - on the cover of her and John’s record Two Virgins: pictured left), who spoke weird English, couldn’t sing and when she did open her mouth spouted hippie mantras. What on earth had happened to John?

Philip Norman, in his most recent, gargantuan Beatles book, John Lennon: The Life (2008), offers a sense of the difficulties of the time: "For the majority of Londoners in 1966, encountering a Japanese person was exceedingly rare. With the war only 21 years distant, attitudes remained coloured by the ill-treatment that the 'Japs' had inflicted on their British and Commonwealth prisoners in southeast Asia. However, the diminutive figure to be seen around Hanover Gate Mansions [where Yoko Ono lived with her then husband Tony Cox] did not arouse hostility so much as bafflement. Her long, unstyled hair crowded in on her face so closely that her eyes and mouth seemed to merge seamlessly with it... her clothes were always concealingly shapeless and funereal black."

Yet for all the bewilderment (and the three other Beatles did, soon enough, find her very trying), Yoko was by the end of the decade there to stay. John had married her and become an unsmiling spokesman for the counter-culture, which is exactly where he wanted to be: anathema to the establishment.

It was at this point that I became a Beatles fan - in fact, a year after the group had broken up. For two intoxicated years - 1971-3 - I wrapped myself up in music and in a story which millions, all at least ten years older than me, had experienced at first hand. I was not, on 1 June 1967, like eight-year-old Mark Lewisohn (today a leading Beatles authority), “shaking his head wildly while trying not to dislodge the cardboard moustache clenched under his nose” as one account has it - I was then six, with no one older in the immediate family to play for me Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released on that day. But when finally I bought the record, cardboard cut-outs included, I did more or less the same thing.

The Beatles were my first love affair. The dream was over: so John sang on his first snarling solo album, Plastic Ono Band, in 1970. But for me it had just begun. I learnt all The Beatles’ tunes and lyrics, and aged twelve performed versions of three songs in front of a prep-school audience (“Can’t Buy Me Love”, “Yesterday”, “You Never Give Me Your Money”). I sounded, perhaps, like a piping, pubescent Paul McCartney. As my voice broke, I found it impossible to imitate the harsher tones of John. I was no rock’n’roller. One thing I could at least do was follow his latest musical move - by buying in 1972 his best solo album, Imagine. There are some quite good things on it, but I was surely far from alone in feeling an inexpressible sadness that Imagine just wasn't The Beatles.

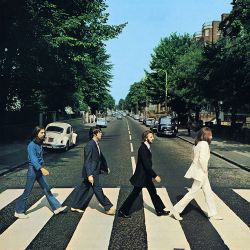

John’s murder eight years later shocked me, deeply. It shocked the world. Disapproval went up in conservative corners of it that such vast acreage of space in newspapers and magazines, and of TV and radio air-time, should be devoted to a pop singer. As is now commonly understood, John Lennon was more than a pop singer. Millions of lives everywhere, precisely because he was a pop singer, had for years been enriched by his music, his off-beat ability with words, his daring. The sum of Lennon, Beatle, musician, madcap poet, was to become - maybe more slowly than many would give the process credit for - greater than his mortal parts. “John, you were the one who imagined it all. You had control of our smiles and our tears all those years ago,” someone calling herself “Jacaranda” once scrawled on the wall of Abbey Road studios, near which lay, until the mid-1990s, probably the most famous zebra-crossing in the world. (Jacaranda, as any Beatles anorak will know and as this one undoubtedly did, was the name of a Liverpool café where the group played in 1960, then as the “Silver Beetles”.) As part of The Beatles, John had had just that effect. He helped anyone who listened to his and the band’s music simply to feel differently.

“John, you were the one who imagined it all. You had control of our smiles and our tears all those years ago,” someone calling herself “Jacaranda” once scrawled on the wall of Abbey Road studios, near which lay, until the mid-1990s, probably the most famous zebra-crossing in the world. (Jacaranda, as any Beatles anorak will know and as this one undoubtedly did, was the name of a Liverpool café where the group played in 1960, then as the “Silver Beetles”.) As part of The Beatles, John had had just that effect. He helped anyone who listened to his and the band’s music simply to feel differently.

At the time of his death, John Lennon and the three others stood for a still immediately recoverable Zeitgeist. The possibility of a Beatles reunion remained one of the world’s most cherished collective fantasies. By the early hours of 9 December 1980 (GMT), Yoko buckling beneath grief, that dream truly was over. The Beatles had penetrated all corners of the globe and, arguably, untapped corners of the human soul. In so doing, they embodied the very essence of an epoch. More perhaps even than Lennon himself, it was the passing of that which was mourned, universally and privately, on that chill morning of 1980.

Matrimony

The decade which puts all this Beatles-nostalgia in its place is of course the 1970s: the so-called hangover decade.

Pop and rock evolved in directions which borrowed something from The Beatles’ late musical ventures - Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd were the mightiest “art” forces in the early 1970s - but absolutely nothing from their PR lightness of touch. Good rock became harder, less generous and more cultist in spirit than it had been in the 1960s. The flip side - bad pop - offered, amongst many offences, the mind-numbing crassness of the Bay City Rollers, the Osmonds and David Cassidy.

It was left to punk, six or seven years after The Beatles disbanded, to bust up (or try to) the inheritance of the 1960s, both the good and the bad, and only in the mid- to late 1980s did it become possible to re-examine what was really good about The Beatles: the profound originality of their music. In the wake of much pop dreariness (did it not in the 1980s become ever more banal?), the time was ripe for reappraisal - and the reappraisal and celebrations haven’t stopped...

John Lennon’s greatest post-Beatles battle was how to survive the new era: one in which he was most emphatically no longer a Beatle - indeed, he was something of a punk, as Plastic Ono Band made manifest, avant la lettre - in which he wanted somehow to be himself and which he shared with a woman who in 1969 had not only become his wife but who probably, more than anyone, when things got bad, pulled him back from complete self-destruction (pictured left: John and Yoko in England at around the time of Imagine).

John Lennon’s greatest post-Beatles battle was how to survive the new era: one in which he was most emphatically no longer a Beatle - indeed, he was something of a punk, as Plastic Ono Band made manifest, avant la lettre - in which he wanted somehow to be himself and which he shared with a woman who in 1969 had not only become his wife but who probably, more than anyone, when things got bad, pulled him back from complete self-destruction (pictured left: John and Yoko in England at around the time of Imagine).

As early as 1964, John was looking for a way of not “being a Beatle”. Some of his songs from that transitional period suggest it. Meeting Yoko two years on, when his first marriage to Cynthia was over in all but name, offered him a real chance to throw his lot in with someone who had no association with The Beatles - as Yoko repeatedly boasted - and who could help him not be what he later called, referring to his almost impossible superstardom, “Elvis Beatle”.

Indeed, had it not been for Yoko, it’s possible that John Lennon, a fearless drug-user and fascinated by the experience of dissolving identity, would have gone the same way as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, even Elvis himself - along with countless others who imitated their lifestyles but had none of their fame. That John survived attests to his peculiar brand of mental toughness, as well as to the care both he and Yoko wanted to give to a highly unorthodox partnership.

Yet given the mess he’d made of his head by 1967, it remains one of the more astonishing facts of his life, and of the 1960s, that from 1968 to 1969 John Lennon still wrote, with his band, outstandingly clever and sometimes deeply moving songs. His love for Yoko and hers for him travel through his and The Beatles’ insinuating, irresistible music from this time, all when Yoko was “arriving”. With the radiant exception of Abbey Road (recorded from February to August 1969), Sgt. Pepper was The Beatles’ last piece of concerted, integrated music-making. The claim is uncontentious. The group had effectively broken up by 1968, a state of affairs gruesomely foreshadowed by the suicide, in August 1967, of their manager Brian Epstein. In spirit, John then left the band and for a time he apparently left the planet, too, with a great deal of help from his new Japanese lover and, increasingly, hard drugs: after LSD, heroin.

This, the “leaving”, was I should stress John’s decision, but one governed largely by his addictions (one of which was Yoko). The Beatles’ late biography cannot be understood unless John’s almost total and frightening narcotism is addressed. Nonetheless, 1968-9 was a period of enormous fertility. The double “White Album” (it was actually called The Beatles: pictured right: John while recording it), Abbey Road and the nemesis out of which Let It Be emerged all belong to it.

This, the “leaving”, was I should stress John’s decision, but one governed largely by his addictions (one of which was Yoko). The Beatles’ late biography cannot be understood unless John’s almost total and frightening narcotism is addressed. Nonetheless, 1968-9 was a period of enormous fertility. The double “White Album” (it was actually called The Beatles: pictured right: John while recording it), Abbey Road and the nemesis out of which Let It Be emerged all belong to it.

It was also one of turmoil in the group’s financial affairs and deepening disaffection between the four. Just how important Yoko had become to John was not really clear until TV viewers witnessed in May 1970 the woeful footage assembled for the film Let It Be, a still depressing insight into The Beatles’ last work, and their last few months, together. Yoko is rarely absent from the screen. Her omnipresence, at the very moment the dream was ending, still invites the question, “Was she to blame?” The question has never stopped being asked and has never been properly answered. But that she advised John how to bring the band to an end, if that’s what John wanted - and it’s my conviction he did - is no longer to be doubted.

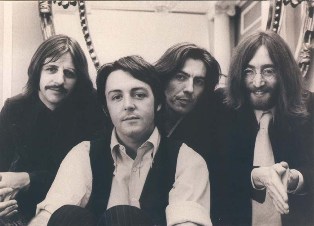

The early 1970s were murkier. With the individual Beatles dispersed (pictured left: The Beatles, at the end), only Paul plausibly pursued a consistent and unembarrassed musical career with Wings. John recorded the two solo albums already mentioned before settling in New York with Yoko, a city she’d first lived in in the late 1950s.

The early 1970s were murkier. With the individual Beatles dispersed (pictured left: The Beatles, at the end), only Paul plausibly pursued a consistent and unembarrassed musical career with Wings. John recorded the two solo albums already mentioned before settling in New York with Yoko, a city she’d first lived in in the late 1950s.

He never set foot in Britain again. And from a wider European perspective, he really was “ours” no longer. Changing his hair-style as frequently as Richard Nixon denied knowledge of Watergate, John’s public status was baffling: so far as could be seen from Britain - Europe - the funniest Beatle was now a bona fide peace person (though patently no longer a hippie), espousing leftish causes, making stacks of contradictory statements, and apparently refusing to have anything to do with the music or the musicians that had made him so famous. Indeed, the musician who seemed to matter to him most now was Yoko Ono, as their UK Christmas hit of 1972, “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” (released in the US in late 1971), and many lesser works of the time made clear. On the single, Yoko’s was a prominent voice, but so - to every Beatles fan’s relief - was Lennon’s, from the first note unmistakably that of our old, friendly John.

Relief was shortlived. Only those close to them knew what a mess the Lennons’ marriage was from 1973-4. Their problems as a couple had really begun when, with The Beatles gone and their achievements eclipsed for a while by some bigger rock sounds in the early 1970s, Mr and Mrs Ono-Lennon had to find a way of moving their marriage forward. After the public pronouncements, peace, Bed-Ins, Bagism and general nuptial euphoria of the late 1960s, to say nothing of drugs and Yoko’s several miscarriages, both were pretty washed up in 1973

John’s darker side took hold, and he binged on drink and drugs in Los Angeles for a year and a half (pictured right: American Lennon). His “lost weekend” marks the lowest point of his life and he really did vanish from the public eye. Moreover, Yoko nearly lost him, indeed nearly chose to lose him, and it says a great deal about each partner’s strength of character - call it mutual need, too - that, against overwhelming odds, they pulled through together to have a son in 1975.

John’s darker side took hold, and he binged on drink and drugs in Los Angeles for a year and a half (pictured right: American Lennon). His “lost weekend” marks the lowest point of his life and he really did vanish from the public eye. Moreover, Yoko nearly lost him, indeed nearly chose to lose him, and it says a great deal about each partner’s strength of character - call it mutual need, too - that, against overwhelming odds, they pulled through together to have a son in 1975.

The Lennons now famously embraced role-reversal. For the second half of the 1970s, it was a brisk and business-like Yoko who took the limelight while John secluded himself inside the Dakota Building, on Manhattan's Upper West Side, and reared Sean - and made no music. When he did return to the studio in 1980, it was with Yoko, in a spirit of jubilation: their marriage had survived. Much of the tragedy of December 1980 is that with their marriage hauled off the rocks, Yoko Ono was witnessing (and taking part in) the first signs of John Lennon’s artistic regeneration since Beatles days. That brief flame of hope, of which the album Double Fantasy is too slight a glimmer, was extinguished in a time-honoured American way: from the barrel of a gun.

Moments before Mark Chapman pulled the trigger, two 1960s fighters seemed to be facing the 1980s with hard-won optimism. Yet no sooner had word got out that John was “back” - and he was - than John was dead. That optimism, a strange and compelling partnership, and, as I see it, an entire epoch were snuffed out overnight.

- Watch The Day John Lennon Died on ITV Player

- Find The Beatles on Amazon.

- Find John Lennon on theartsdesk

- Read Part 2 of John Lennon's Love and Death

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment