I Can't Stop Stealing, BBC Three | reviews, news & interviews

I Can't Stop Stealing, BBC Three

I Can't Stop Stealing, BBC Three

Crass journalism interested only in pictures, not questions

As a journalist with a sense of pride about what we reptiles can achieve, sometimes I shudder at the awfulness of what passes for journalism. The licence fee in theory confers on the BBC some moral purpose higher than that of the base commercial stations, doesn’t it? (Given that it implies Commercial = Bad, Public Service = Good.) So a BBC Three documentary on shoplifting should probably be an example of higher journalism? Maybe something that rams home deeper truths either about the distinction between good and bad, or about disturbed individuals?

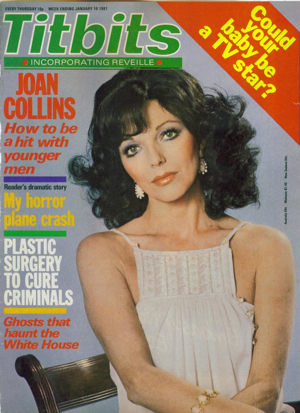

Look, I know what BBC Three fare is. Just before I Can’t Stop Stealing aired, we had a trailer for the channel's "Adult Season", all about the “extraordinary stories” of kids (mostly) who are bad/ non-conformist/ criminal/ weird/ freaky. Early in my life I briefly worked for saucy little Titbits magazine (pictured below, 1981), helping quite ordinary stories along with penny-dreadful headlines, for which it enjoyed a risqué reputation. But Titbits didn’t pretend to be high-grade and ask for a subsidy. BBC Three is one of the arguments that Mark Thompson deploys to justify the licence fee and the BBC’s global reputation for, er, high-grade documentary journalism as well as edgy comedy. Well, I’m edgy nowadays too, and it’s about watching terrible TV on serious subjects.

Shoplifting needs high-grade journalism. It is a grave problem in Britain. We were told - tellingly not by a journalist but by a voiceover artist (Amanda St John who did Boddingtons ale) - that Britain has the worst shoplifting problem in Europe.

Shoplifting needs high-grade journalism. It is a grave problem in Britain. We were told - tellingly not by a journalist but by a voiceover artist (Amanda St John who did Boddingtons ale) - that Britain has the worst shoplifting problem in Europe.

Come again? Figures? Comparisons? One crime a minute somewhere in Britain, said the lady’s voice. We were given not a single further fact or inquiry to prove or inform the context. But isn't such a gigantic problem a moral problem for society? As well as a political one? Does television actually want to address immorality or does it want to pursue, without genuine interest, token “extraordinary stories”?

You don’t get the second by being judgmental - and you don’t get the first by fielding such TV-savvy personalities as its featured characters last night. While it may not be easy to find shoplifters ready to appear on telly, it’s a fair bet those who make it through the edit will be people who want to be on telly (so may have done what was necessary to get there).

Seventeen-year-old Emily, 46-year-old Jenny, and twentysomething Nathan all came clean for the camera about their past misdemeanours and their determination to reform. I reckoned that despite all their best plans none of them would, probably: Emily, because she has so little else in her life, Jenny, because she had been addicted to shoplifting for 40 years (she started at six - who started her?), and Nathan, because he was bereft and traumatised after his imposing father's death. Three separate sets of problems, at least two of them deep-seated psychological ones - against which we had glimpses of the security guards who watch CCTV and catch them at it, and the police officers who decide whether to issue them fixed-penalty £80 notices or to send them to court.

Which was where the final problems existed. A middle-aged methadone addict caught caching £187-worth of clothes around her ample person was duly denied an £80 fine by the police officer and sent up to court. She was sentenced to a caution - whether before or after telling the camera that actually she had several prison sentences already and “nothing will ever put me off” wasn’t clear. You deduce that not even the legal establishment is sure whether stealing from shops is as bad as stealing from people.

The effect of this 45 minutes was to iron out all moral difference, all human difference. Evidently Emily knew perfectly well she was doing wrong and like many teenagers enjoyed running rings around her mother. Evidently Jenny’s daughters’ lives were blighted by the shame of their mother’s habit and she couldn’t make their misery matter to her more than the approval of a so-called friend who was delighted to wear her stolen goods. Evidently Nathan’s hopeful mate Bill thought there ought to be by rights a business opportunity for offenders to financially exploit their crimes by “advising” stores where they were going wrong. Surely good and bad should have been disentangled here?

Further unanswered matters: what about the labyrinthine psychology of shoplifting and shop display, none of it explained here? Shops use mind games to display their wares to lure shoppers, but shoplifters use better mind games. People start stealing to get the buzz (youngsters usually), or to get approval from a parental figure, but they go on past the buzz phase because of deeper addictions, either purposely to sell stolen stuff on eBay to buy drugs, or for reasons they can’t explain but which keep them as reluctantly dependent on shoplifting as on a heroin fix. Jenny’s house, packed to the gunwales with clothes she would never wear and chocolates she would never eat, was the visible evidence of a psyche as messed-up as they come. BBC Three only wanted the sight of her stuffed shelves and overflowing cupboards. They weren’t that interested in questions, not as much as the camera access.

This is the kind of low-grade cop-out that makes me ashamed of my fellow journalists, as well as furious as a BBC licence-payer. Mark the credits (in the same way that the store detectives mark likely re-offenders): executive producer Samantha Anstiss, whose past highlights include Amy: My Body for Bucks, an exposed example of not letting the facts get in the way of a story, and filmed, written and directed by Bruce Fletcher (famed primarily for his voyeur doc Saving Britney Spears).

more TV

Blue Lights Series 2, BBC One review - still our best cop show despite a slacker structure

The engaging Belfast cops are less tightly focused this time around

Blue Lights Series 2, BBC One review - still our best cop show despite a slacker structure

The engaging Belfast cops are less tightly focused this time around

Baby Reindeer, Netflix review - a misery memoir disturbingly presented

Richard Gadd's double traumas are a difficult watch but ultimately inspiring

Baby Reindeer, Netflix review - a misery memoir disturbingly presented

Richard Gadd's double traumas are a difficult watch but ultimately inspiring

Anthracite, Netflix review - murderous mysteries in the French Alps

Who can unravel the ghastly secrets of the town of Lévionna?

Anthracite, Netflix review - murderous mysteries in the French Alps

Who can unravel the ghastly secrets of the town of Lévionna?

Ripley, Netflix review - Highsmith's horribly fascinating sociopath adrift in a sea of noir

Its black and white cinematography is striking, but eventually wearying

Ripley, Netflix review - Highsmith's horribly fascinating sociopath adrift in a sea of noir

Its black and white cinematography is striking, but eventually wearying

Scoop, Netflix review - revisiting a Right Royal nightmare

Gripping dramatisation of Newsnight's fateful Prince Andrew interview

Scoop, Netflix review - revisiting a Right Royal nightmare

Gripping dramatisation of Newsnight's fateful Prince Andrew interview

RuPaul’s Drag Race UK vs the World Season 2, BBC Three review - fun, friendship and big talents

Worthy and lovable winners (no spoilers) as the best stay the course

RuPaul’s Drag Race UK vs the World Season 2, BBC Three review - fun, friendship and big talents

Worthy and lovable winners (no spoilers) as the best stay the course

This Town, BBC One review - lurid melodrama in Eighties Brummieland

Steven Knight revisits his Midlands roots, with implausible consequences

This Town, BBC One review - lurid melodrama in Eighties Brummieland

Steven Knight revisits his Midlands roots, with implausible consequences

Passenger, ITV review - who are they trying to kid?

Andrew Buchan's screenwriting debut leads us nowhere

Passenger, ITV review - who are they trying to kid?

Andrew Buchan's screenwriting debut leads us nowhere

3 Body Problem, Netflix review - life, the universe and everything (and a bit more)

Mind-blowing adaptation of Liu Cixin's novel from the makers of 'Game of Thrones'

3 Body Problem, Netflix review - life, the universe and everything (and a bit more)

Mind-blowing adaptation of Liu Cixin's novel from the makers of 'Game of Thrones'

Manhunt, Apple TV+ review - all the President's men

Tobias Menzies and Anthony Boyle go head to head in historical crime drama

Manhunt, Apple TV+ review - all the President's men

Tobias Menzies and Anthony Boyle go head to head in historical crime drama

The Gentlemen, Netflix review - Guy Ritchie's further adventures in Geezerworld

Riotous assembly of toffs, gangsters, travellers, rogues and misfits

The Gentlemen, Netflix review - Guy Ritchie's further adventures in Geezerworld

Riotous assembly of toffs, gangsters, travellers, rogues and misfits

Oscars 2024: politics aplenty but few surprises as 'Oppenheimer' dominates

Christopher Nolan biopic wins big in a ceremony defined by a pink-clad Ryan Gosling and Donald Trump seeing red

Oscars 2024: politics aplenty but few surprises as 'Oppenheimer' dominates

Christopher Nolan biopic wins big in a ceremony defined by a pink-clad Ryan Gosling and Donald Trump seeing red

Add comment