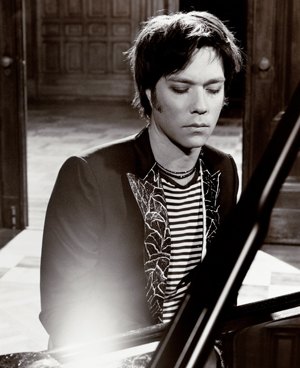

To be born into the extraordinary Wainwright dynasty is to be born onstage, and Rufus has seized his birthright in a giant bear-hug. Mere weeks after the death of his mother, Kate McGarrigle, from cancer in January, the lanky, somewhat Heathcliff-like Rufus was back on the campaign trail with throttles wide open. In the pipeline for early April are his new album, All Days Are Nights: Songs for Lulu, and a new production of his opera Prima Donna at Sadler's Wells.

Rufus has grown up in public, and that's where he feels most comfortable. More retiring personalities might have locked themselves away to ponder the meaning of fate and mortality, but if you want to talk, he’s happy to oblige.

"Yeah," he agrees, hooking up down the phone from New York, "for one thing, I'm not the only one grieving my mother's loss. She had a lot of fans. Her and [her sister] Anna's relationship was an integral part of an era. Later on, our relationship - my mother's with me and also with my sister Martha - meant a lot to a lot of people on many levels. I feel the need to celebrate her and share her legacy with adoring fans."

Inevitably, he has still been feeling Kate's presence strongly in everything he does. The aftermath of her death keeps surging over him in powerful waves.

"I'm still processing it on many levels. I see her everywhere, whenever I'm doing anything creative or watching something that touches on death, which a lot of things do. For instance I was singing Berlioz's Les nuits d’été recently, a classical song cycle about death. I try to function and not necessarily not feel it, but I know it's gonna come, you know? I'm building up my strength a lot of the time, knowing full well that it will be devastating instantaneously."

His album All Days Are Nights inevitably fell under the shadow of his mother's illness, but a variety of other concerns fed into its creation. The pieces on it, he explains, fall into four categories.

His album All Days Are Nights inevitably fell under the shadow of his mother's illness, but a variety of other concerns fed into its creation. The pieces on it, he explains, fall into four categories.

"Probably the earliest is the French aria from my opera Prima Donna, 'Les Feux d'artifice t'appellent', that's always been looming," he explains (at his mother's wake, “Les Feux” was sung by Scottish soprano Janis Kelly). "Then there are three settings of Shakespeare sonnets which I wrote for Robert Wilson's Sonette production in Berlin last year, which were kind of like musical messages between stages of my life. Then there are ‘What Would I Ever Do with a Rose?’ and ‘True Loves’, which come from an imaginary musical I've been thinking about for a couple of years. And then the other songs are just from my life y'know, ‘Martha’ and ‘Who Are You New York?’ My plain old life."

In the case of this exuberantly self-styled "gay messiah", that life would be about as plain as a pink Cadillac with gold lamé antlers, leopardskin upholstery and mink-lined fenders. But the album is at least relatively unadorned in one respect, which is that it's performed solo on piano by Wainwright, with no bands, orchestras or electronic enhancements within earshot.

"Again this pertains to my mother," he continues, "because she was one of the great improvising musicians, she could just get up there and play with anybody. It's something I've never been able to do and that's something I've always lamented. My style is very, very constructed. I spend months and months on certain passages. I figured that since I'll never be able to jam like my mom, I might as well keep running the other way and really solidify my classical style."

Plonk Rufus in front of a piano and fireworks are inevitable. This was never going to be an exercise in faux-naif two-fingered noodling, and Wainwright is off at the gallop with the turbulent, unrelenting motion of “Who Are You New York?” Also dense with energetic keyboard flourishes and whirling-dervish fingering are “The Dream” and the florid “True Loves”, while “Give Me What I Want And Give It To Me Now” sounds like the entire history of ragtime parading up Broadway under a blizzard of ticker-tape.

The "Songs for Lulu" aspect of the disc is connected to his ideas about an imaginary musical. Wainwright harbours an infatuation with Louise Brooks' performance as Lulu in G W Pabst's 1929 movie Pandora's Box, though as an opera buff he's aware of Alban Berg's Lulu, and of Frank Wedekind's original Lulu plays too. The Lulu character is an amoral, archetypal femme fatale who hacks a trail of devastation through the lives of the people closest to her, a saga which strikes a loud chord with Wainwright. He went through a wild party-going period that ended in crystal meth addiction and rehab, and doesn't delude himself that his destructive urges are gone for good.

'Tiger Woods is a great example of what happens when you don't acknowledge the dark side'

"I've discovered in my 30s that a lot of those reckless and nihilistic feelings I once had in my 20s didn't necessarily go away when I became more of an adult," he reflects. "I think Tiger Woods is a great example of what happens when you don't acknowledge the dark side. You become this kind of iconic symbol of wholesomeness, and so in watching all this I think it's important to send these sacrifices over to the bar down the street. It doesn't mean you have to go there and partake, but I think you definitely have to acknowledge the other thing that's going on in your life."

But the disc isn't all high drama and pyrotechnics, and it lands some of its most forceful emotional punches when Rufus manages to throttle back a couple of notches. His settings of the Shakespeare sonnets are framed within probing, Debussian chord patterns, while the closing track, “Zebulon”, exists in a zone of ghostly weightlessness.

The latter refers to "a guy I went to school with and I had a kind of pre-pubescent crush on before I knew quite what the jig was. I spent a lot of time with this kid Zebulon. But that's one of the songs I'm very very fortunate to have been gifted by God knows who. I didn't spend a lot of time writing it, I obviously didn't spend much time on the piano arranging it, but somehow it just arrived fully formed and I had my marching orders."

Perhaps the most touching of all is “Martha”, a song to his sister written while he was in Berlin working on the Robert Wilson project.

"We were desperately trying to get Kate over for the premiere, but she'd had this sort of botched medical procedure and was in hospital with an infection. She later got to see the piece and I'm very happy about that, but she didn't make it to the premiere and I was torn between having to work mindlessly getting the show up and once again processing all this tragic material going on in my own life.

"It was one of those moments when I needed my sister desperately, and she was the only person on earth who could relate to what I was going through. She was on the other side of the ocean and I was sort of calling out to her, and she did call me back eventually - it always takes a couple of days with her! I think the song was setting the stage for our new relationship, which was about facilitating our mother's passing, and that we would have to come together on a new level and really take care of each other."

Wainwright is taking the new songs on tour in April, playing them solo within a stage production devised by Douglas Gordon. "It will be completely classical," he promises, "meaning that there won't be any applause between songs. It'll be done as a song cycle with a dirge-like, sad, dark, tragic feel. I'm going for that jugular."

These classically inclined live shows will dovetail with a new production of Prima Donna, which opens at Sadler's Wells on 12 April. Wainwright's emotional fearlessness is one of his most exhilarating traits, but even he was chewing his nails and tearing his hair before Prima Donna made its world premiere at Manchester's Palace Theatre last July. Pop singer writes opera? It was like inviting critics to arrive wearing butcher's aprons and carrying chainsaws.

"Certain people adored it, certain people hated it, but in the end it survived, which is much more than can be said for a lot of far more famous pop stars than I who wrote theatrical pieces," he reflects. "So I'm pretty thrilled with the response. In fact if all the critics had come out and said, 'Oh we adore it, we think it's amazing!' I think that would have been worse. It would have been like, 'Where do I go from here?'"

"Certain people adored it, certain people hated it, but in the end it survived, which is much more than can be said for a lot of far more famous pop stars than I who wrote theatrical pieces," he reflects. "So I'm pretty thrilled with the response. In fact if all the critics had come out and said, 'Oh we adore it, we think it's amazing!' I think that would have been worse. It would have been like, 'Where do I go from here?'"

Indeed, he insists that he welcomes the rigour of classical music reviewing. That's his story, and for the moment he's sticking to it.

"I think there's something in the sharp nature of classical criticism that propels the music forward to really make its mark," he declares. "There's no room for dilettantism, and I'm happy to be in that arena because I have as much respect for the form as those critics do and I want it to be as good. I'm not saying they're right by any means, but I do like a sharp knife to look out for. But the greatest triumph was that above all the criticisms, the paper that loved it the most was Le Monde. Their classical critic is one of the toughest in Europe and he got immediately what I was trying to do."

What's beyond doubt is Wainwright's passion for opera. Its heightened emotions and lavish theatricality might have been designed for him, and he's enthralled by the medium's rich history of brilliant composers and tragic divas. "Opera has been my religion and my saviour," he once commented. He's still haunted by the memory of seeing Parsifal at Bayreuth with his mother after her cancer had been diagnosed, which he found "an incredibly healing and enlightening experience in terms of the releasing power of death. She still had a wound herself from that botched procedure, and that's what the opera is all about, this wound that won't heal. There have been a lot of eerie parallels in opera with my mother."

He has no pretensions towards reinventing the harmonic and dramatic language of opera - "I'm not trying to modernise the form, and I have no qualms about borrowing from all the greats" - but he's working steadily to improve. For Sadler's Wells, Tim Albery replaces original director Daniel Kramer ("Daniel was a little bit, y'know, whatever, Cecil B. DeMille-ish about the whole thing, so now we're making it more about my piece"), though the score has undergone only minor tweaking. Not that he's claiming it's perfect. Behind his flamboyant self-mythologising, Rufus is a shrewd judge of where he's at and how far he has to travel.

"I would be an idiot if I ever said that Prima Donna was my masterpiece. I think it has an incredible soul and has moments in it that are really unique. I think it's a very special piece that will always have something that my other operas won't. But nonetheless it is my first. When you look at Wagner or Verdi or Janáček, there's always a wide plain you have to cross to get to the gold."

As the old proverb says, a journey of 1,000 miles must begin with the first step.

- Wainwright tours the UK from April 11 - Rufus Wainwright tickets on Seetickets

- New album All Days are Nights: Songs for Lulu on Amazon

- Prima Donna is at Sadler's Wells on 12, 14, 16 and 17 April

- Check outwhat's on at Sadler's Wells this season

YouTube Video - Rufus Wainwright talks about his new album

Add comment