theartsdesk Q&A: musician Susanne Sundfør - ‘Blómi is a message of hope for whoever might need it’ | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: musician Susanne Sundfør - ‘Blómi is a message of hope for whoever might need it’

theartsdesk Q&A: musician Susanne Sundfør - ‘Blómi is a message of hope for whoever might need it’

Interviewed about her new album, the Norwegian singer-songwriter reveals its inspirations - family, flowers and much more

With the release this week of Blómi, her sixth studio album, Norway’s Susanne Sundfør discloses more about herself than she previously has through her music – but nothing is made obvious. As she says during this interview, the driving concept became complex.

Fortunately, she’s open to discussing the album in depth. Rather than revisiting old territory, catching up with her at home via Google Meet brought the opportunity to dig into Blómi, the creative processes behind it and learn how she sees it and its personal context – as well as veering off into associated tangents. She’s analytical, animated and clearly delighted with how the album has turned out.

Blómi follows-up 2017’s Music For People In Trouble, an album largely drawing on her travels around the world. In contrast, a prime motivation for Blómi is getting to grips with what’s closer to home: family and its impact. After Music For People In Trouble there was a measured flow of releases: 2019’s Music For People In Trouble Live From The Barbican album; 2020’s digital-only Self Portrait Original Soundtrack which featured contemplative solo music she composed for a documentary about anorexic photographer Lene Marie Fossen. Following this, she and musician André Roligheten married – he had played on Music For People In Trouble – and their daughter was born. After this brief interregnum, a return to music came in 2022 when she collaborated with Röyksopp on their two Profound Mysteries albums – they had worked together before. Now, she returns with her own album. "Blómi" translates from Old Nordic as “bloom” or “flower” – many of the abum’s song titles are in Old Nordic.

Blómi follows-up 2017’s Music For People In Trouble, an album largely drawing on her travels around the world. In contrast, a prime motivation for Blómi is getting to grips with what’s closer to home: family and its impact. After Music For People In Trouble there was a measured flow of releases: 2019’s Music For People In Trouble Live From The Barbican album; 2020’s digital-only Self Portrait Original Soundtrack which featured contemplative solo music she composed for a documentary about anorexic photographer Lene Marie Fossen. Following this, she and musician André Roligheten married – he had played on Music For People In Trouble – and their daughter was born. After this brief interregnum, a return to music came in 2022 when she collaborated with Röyksopp on their two Profound Mysteries albums – they had worked together before. Now, she returns with her own album. "Blómi" translates from Old Nordic as “bloom” or “flower” – many of the abum’s song titles are in Old Nordic.

On Blómi, Sundfør plays acoustic guitar, piano and synthesiser. Nikolai Hængsle Eilertsen plays bass and Ståle Storløkken is on keyboards and synthesisers – both are in Elephant9 as well as playing and recording in other configurations. Gard Nilssen is on drums and André Roligheten is on wind instruments – they play together in Gard Nilssen’s Acoustic Unity as well as, unsurprisingly, in other configurations. Hardanger fiddle player Erlend Viken is heard on “Alyosha”, bringing the traditionally Norwegian to the album. There are also two vocal appearances by musician and therapist Eline Vistven. Sundfør 's producer and regular studio collaborator Jorgen Træen is also heard on synthesiser. All are musical boundary pushers – whether with jazz, folk or idiosyncratic rock – and most have a track record with Sundfør. Unlike Music For People In Trouble, everyone heard is Norwegian. Blómi’s contributors are not from the musical mainstream, yet the album is thoroughly accessible.

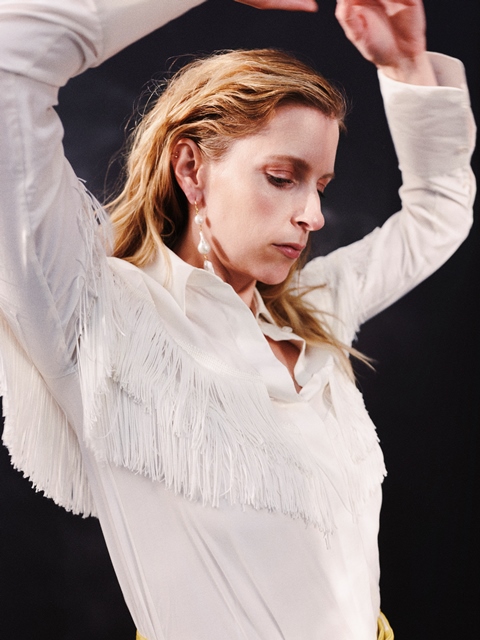

Nonetheless, there is a lot to discover. There’s the role in its creation of her grandfather, academic and theologian Kjell Aartun. She is seen with him on the cover in a photo taken by her mother, Inge Sundfør (pictured above right). There’s what she wants to say to her daughter. There’s her desire for the album to seen as a necessary message of hope. And, then, there’s how she’s always been a weirdo.

KIERON TYLER: Tell me about the background to Blómi and its gestation.

SUSANNE SUNDFØR: It was fragments until last year. At the beginning of 2022 I suddenly had this idea it would be really cool to make an album about flowers. I was thinking each song would be a flower, it would be very soft and feminine and all these things flowers are supposed to be – vulnerable and pretty. The concept got a bit more complex than my original idea. The flower-power element is still there, but there is a lot more information, more happening than just flowers.

'Blómi' is partially a message to my daughter but also meant as gift to all my family

Why flowers?

I read in this book The Woman in the Shaman's Body [by anthropologist and shaman Dr. Barbara Tedlock, published in 2000] that flowers are a symbol in some indigenous cultures of woman’s fertility blooming and also a symbol of menstruation in some cultures, and I thought that these were interesting images and symbols for all the themes on the album – blossoming in nature but also in our bodies and minds.

It's also a mother-daughter album?

It is, but it’s also dedicated to my family. So it's partially a message to my daughter but also meant as gift to all my family.

A gift looking for positivity when the world isn’t too filled with the positive?

Yes, it’s for the next generation of my family and for the previous generations as my family history is quite interesting. My grandfather Kjell Aartun worked as a linguist, in theology. He studied ancient languages and he found a lot of fertility images which could be quite erotic in character at times, and that is also part of the symbology I used – I used his words in the songs, like the waning moon in”Ashera's Song” is from one of his books. I mixed his fascinations, his writings on ancient texts with Tao and [imagery from] animist religions to create this symbolic world, an optimistic view of the world which celebrates life and fertility. It encapsulates all of this.

Which languages was he studying?

Minoan, Cretan, Etruscan… He specialised in Semitic languages and was also fluent in Arabic, Hebrew, the Ugaritic languages. He specialised in dead languages and saw connections between the Minoan language and Semitic languages. A lot of different theories. He had a theory that people were mobile, travelled more than was supposed and may have settled in Norway alongside the tribes here – he thought there were more mixed cultures here. He points to the ornamentation in [Norwegian] stave churches for example, animal motifs. He said he saw the same things in cities in southern Europe. He wrote a popular book where he talks about these theories [1994’s Runer i kulturhistorisk sammenheng: En fruktharhetskultisk tradisjon]. My mother knows much more.

Were you aware of all this when you were a kid?

Were you aware of all this when you were a kid?

I learned things that maybe other kids didn’t learn [laughs]. We maybe had a different history lesson to in other homes [laughs more]. I learnt about fertility cults, where European civilisation is from – he called the Minoan civilisation the first European civilisation. We are a family of quite curious people, loving to explore, so it was a feast for me. It was really fun, and I’m really happy about that.

Did this knowledge from home make you an irritating kid for teachers at school? Were you a bit of a weirdo?

I’ve always been a weirdo, it didn’t happen recently. I’ve always known I’ve been different and eccentric, which is why I wanted to dedicate this album to my family. I don’t know about England, but it’s difficult to be different in Norway – it’s frowned on. I loved reading books as kid I guess I was like [the Harry Potter book’s] Hermione. I loved knowing answers, I was eager to learn. Definitely nerdy. It was a difficult time for me, difficult to be different. That part of my family has always been outside society. My grandfather was an academic who didn’t fit well with his contemporaries but still insisted on doing his job. When you’re an academic and ridiculed in the media – it didn’t just happen to my grandfather, it happened to his family as well. So growing up in a country where being seen as eccentric is frowned upon – that’s heavy.

How was he ridiculed in the media?

People who wrote about him said he was pseudo-scientific. The things that he found were often erotic, so the reaction was ridicule. But he was just being an honest academic: he found truth in what the languages were saying and presented that to the world.

The album opens and closes with the voice of Eline Vistven, not yours.

It was a [recording] session I had with her. She is a friend, also a musician. I don’t how to define what she does. She has an ability I don’t understand. I came to her during the pandemic because I had heart problems. I had heart arrhythmia, it felt like my heart was living its own life. Suddenly one day you wake up and its forcibly beating, skips a beat, then suddenly beats really fast. In a way it's saying there is something wrong with me – I had never had that before.

If you live in a world where everything can be explained that’s a poor world, one without imagination

Could that be pandemic stress?

I don’t know. I’m totally open to that being a factor, my baby was six months old and there was sleep deprivation too. So stress is an explanation that makes sense. But at the same time I wondered if it had anything to do with the virus. I had covid before I had the vaccine. So I don’t know – could be physical, could be mental, could be both. I went to Eline, she looked at me and said “it’s really tight in there”, and I have not had any palpitations since then. A doctor would say it's a placebo, I have no idea what she did. The mystery of not knowing, when we're so obsessed with finding truth and I want to know that, but I really like being challenged by the notion of not knowing. It’s the same when I explain an album I made – as if you can decipher art. Art is all these elements, all the reasons that made it plus what you get out of it. That’s the truth. That’s also the challenge I make with this album where there are connections and energies which cannot be defined. That’s beautiful. To me, if you live in a world where everything can be explained that’s a poor world, one without imagination.

How did you choose who you play with on the album – there are musicians you’ve worked with before and there is also the Hardanger fiddle, a traditionally Norwegian instrument which is new with you.

I wasn’t thinking about the bands [anyone is in]. These guys play with ten different bands. Ståle and Nikolai have so many different set ups. Gard and I have played the since I was 23, we work so well together, he's a fantastic drummer. André I’ve worked with since Music For People In Trouble, I love his musicality – he’s also my husband. I’ve never played with Ståle before but I loved his The Haze Of Sleeplessness album from 2019. Erlend, who plays fiddle, I found out about through musician friends.

What’s your relationship with traditional music?

I’m not schooled but, then again, my impression schooled is a term folk musicians don’t necessarily like. I used to do some kveding [vocal folk music form] in my twenties, and I wish I had done more. One album which keeps coming up when I’m asked to pick my favourite albums is Odd Nordstoga’s Nivelkinn from 2002 [made with Øyonn Groven Myhren: a folk-music setting of poetry by Aslaug Vaa]. Growing up, I’ve been inspired by the focus on melody in folk music and it’s the same with church music.

There’s a gospel feel to the album’s "Fare Thee Well” and "Leikara Ljóð”.

There’s a gospel feel to the album’s "Fare Thee Well” and "Leikara Ljóð”.

I wanted to join a gospel choir when I was in my teens – they asked if I was a Christian and I said no. I was brought up to be honest, so I wasn’t allowed to join which was understandable. Also, I’ve always been a huge fan of Bill Withers. I love his arrangements, the vocals – his "Do it Good” was a direct inspiration on "Blómi”, the title song.

You don’t limit what you say to the music.

I’m quite active on Instagram, I say some political things, on climate change. I really feel for younger people, there’s so much anxiety. Media outlets saying there’s no hope. The worst case scenario is shown all the time. That’s not helpful. I want this album to be an antidote to all this scaremongering. I saw in The Guardian someone saying "we're all going to burn up and die”. What kind of message is that? I want it [the album] to be a message of hope for whoever might need it.

Is it necessary to constantly have a message of hope?

No, we are all human and feel despair. It’s more about the mode of it, the public conversation. Yes, there are a lot of fucked-up things going on in the world but I feel young people need to learn about solutions and see different perspectives. Climate activists do not need to be so extreme in their rhetoric. Take one example, you flying to somewhere doesn’t mean you’re a horrible person, eating a steak doesn’t mean you’re a horrible person. It’s almost [as if] one of the most controversial things you can do today is gather around our family and friends and enjoy a wholesome meal. It’s such a toxic climate. There’s this book Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Kimmerer, she wrote that humanity, human beings, have an essential function in nature – do you want to embrace that kind of world instead of condemning yourself for being born? Why not turn it around and say "I have a purpose here, see how I can fit into nature and this world and see how I can do something good”. Enjoy creating life. And that’s what the album is about.

A message you would like to get over to your daughter?

Yes.

- Blómi is released on 28 April 2023

- Read more music interviews on theartsdesk

- Kieron Tyler’s website

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

theartsdesk on Vinyl 93: Led Zeppelin, Blawan, Sylvester, Zaho de Sagazan, Sabres of Paradise, Hot Chip and more

The most extensive, wide-ranging record reviews in the galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 93: Led Zeppelin, Blawan, Sylvester, Zaho de Sagazan, Sabres of Paradise, Hot Chip and more

The most extensive, wide-ranging record reviews in the galaxy

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Add comment