In May 1981, a new-minted music graduate newly embarked on a career in journalism, I was pleased as punch to secure a commission from Capital Radio. Forever Young: Dylan at 40 was broadcast on 24 May. I’ve a tape of it somewhere, this 30-minute programme voiced by a guy more suited to Carlsberg ads. The script – written using a golf-ball typewriter, music cues in its wide margins, hints of Tippex here and there – turned up a couple of weeks ago as I tidied my study. I was 23, younger than Bob Dylan when he wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind”, and 40 then seemed rather old.

Dylan's career was at one of its low points – the musical triumph of the 1978 world tour had given way to lacklustre gospel, as rock’s angry young man embraced born-again Christianity – and it seemed unlikely that 40 years on he would still be making albums and making waves. I’d recently published Conclusions On the Wall: New Essays on Bob Dylan to which, rather remarkably, the TLS had devoted a lengthy review, doubtless on account of contributions from Wilfrid Mellers and Christopher Ricks, two professors quick to laud Dylan’s talent. To coin a phrase, I thought I’d “got it made”!

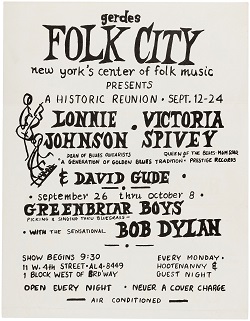

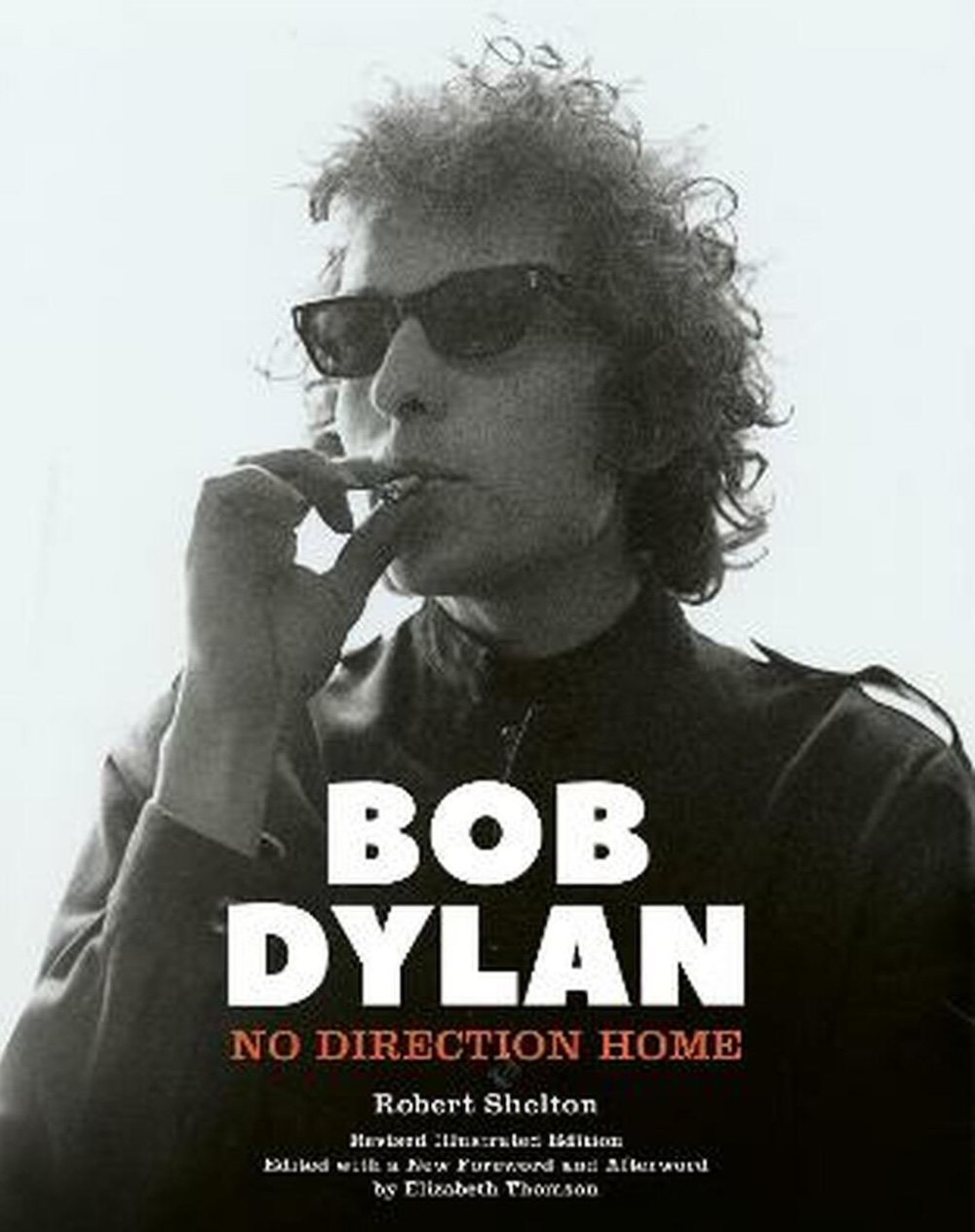

I’m 63 now, and Dylan turns 80 today (24 May) and it seems we’re both still at it! He’s not the first rock star to reach that milestone, but none has been granted such lavish attention: a conference at his very own museum; a week-long Radio 4 series and a drama; countless articles, most rehashing the same old story; and of course, more books, including Bob Dylan: No Direction Home by Robert Shelton, my friend and mentor and the New York Times critic whose celebrated review launched Dylan’s career (pictured below, handbill for Gerdes Folk City, advertising Bob Dylan's two-week residency) .

On 29 September 1961, under the four-column headline “Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk-Song Stylist”, Shelton wrote that “A bright new face in folk music is appearing at Gerde’s Folk City. Although only 20 years old, Bob Dylan is one of the most distinctive stylists to play a Manhattan cabaret in months”. Resembling “a cross between a choirboy and a beatnik”, his work bore “the mark of originality and inspiration, all the more noteworthy for his youth”. The review concluded: “Mr Dylan is vague about his birthplace and his antecedents but it matters less where he has been than where he is going, and that would seem to be straight up”.

On 29 September 1961, under the four-column headline “Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk-Song Stylist”, Shelton wrote that “A bright new face in folk music is appearing at Gerde’s Folk City. Although only 20 years old, Bob Dylan is one of the most distinctive stylists to play a Manhattan cabaret in months”. Resembling “a cross between a choirboy and a beatnik”, his work bore “the mark of originality and inspiration, all the more noteworthy for his youth”. The review concluded: “Mr Dylan is vague about his birthplace and his antecedents but it matters less where he has been than where he is going, and that would seem to be straight up”.

Suze Rotolo, the girlfriend pictured on the sleeve of his 1963 album Freewheelin’ walking arm-in-arm with the baby-faced Dylan through the Jones Street slush, recalled it as “over-the-top exciting. We got the early edition of the paper late at night at the newspaper kiosk on Sheridan Square, and went across the street to an all-night deli to read it. Then we went back and bought more copies… Robert Shelton had been around the clubs and bars for ages, seeing every new and old performer, but he’d never written a review quite like the one he wrote for Bobby…” Within a couple of weeks, Dylan had signed a record contract.

Robert Shelton died in December 1995, having spent the last 15 years of his life in Britain, latterly as arts editor of the Brighton Evening Argus, his health and his finances broken by a twenty-year struggle to write a serious biography of the man who, as early as 1963, he’d hailed as “the singing poet laureate of young America”. The book that was eventually published in 1986 was the result of a titanic battle over taste and aesthetics. The American editor who’d acquired it in 1966 saw no virtue in a serious study and called instead for more blood and gossip, which Shelton declined to provide. A London editor eventually took over the project but, while respectful of Robert’s aims, he had somehow to make sense of a book that was not only very long, but also long overdue while dealing with an author by then convinced that publishers cared only for the bottom line.

Robert and I had become friends following a chance meeting at a Dylan event in Manchester in 1979. A few months later, he asked me to read his “much-mauled manuscript” and comment on it, a daunting task at the time. It felt like the Rosetta Stone! As it finally began its editorial journey toward publication, I was given the official task of photo research – and the unofficial task of conciliating between author and editor. Published to mark the 25th anniversary of that Times review, No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan was, Robert felt, “abridged over troubled waters” and he always hoped to return to it. In the event, my 2011 restoration, all 225,000 words and done with the blessing of his family, was essentially the book he’d wanted to publish, way back when.

This new 80th birthday edition, carved from it, is a shorter narrative biography with all the immediacy of Robert’s magical eye-witness account, which takes the reader back “down the foggy ruins of time” to Dylan’s formative years in Greenwich Village, when the two Bobs hung out together. Robert was the only journalist to interview Dylan’s parents and he was present at all the key moments in Dylan’s turbulent career. The long and candid freewheeling interview aboard Dylan’s private jet early in the 1966 tour, a flight from Lincoln, Nebraska to Denver, Colorado at the break of midnight, remains at the heart of the book.

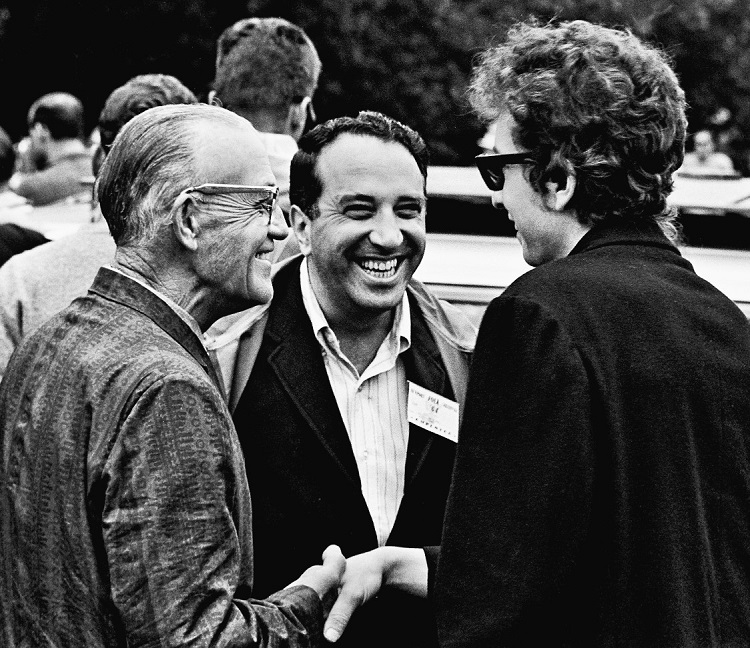

Shelton – whom the Grammy-garlanded Janis Ian regards as “the father of rock journalism” – was perspicacious and not everyone understood his seeming rush to judgment. But Robert’s belief was born out with the 1963 release of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, his second album, and his debut as a fully-fledged songwriter. It opened with “Blowin’ in the Wind’”, which long ago became part of our cultural DNA, our lingua franca, and it included two other of his most celebrated protest songs: “Masters of War” and “A Hard Rains-a-Gonna Fall”, as well as one of his most enduring love songs, “Girl from the North Country”, and anti-love songs, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” (pictured below by Joe Alper: At the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, Robert Shelton (centre) introduces Dylan to fiddler Clayton McMichen).

At the age of just 22, the man born Robert Allen Zimmerman had taken poetry off the bookshelves and placed it on the jukebox. And what poetry! “A Hard Rain”, written as the 1962 Cuban missile crisis unfolded, compresses innumerable song ideas, written in 10-cent notebooks in Village coffehouses. “I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put them in to this one,” Dylan explained, of a song in whose lyrics can be discerned echoes of Eliot, Lorca, Rimbaud, Ginsberg and many besides. It’s Dylan’s own nightmare war vision: Picasso’s Guernica set to music. “A Hard Rain” inspired a young Canadian poet named Leonard Cohen to try his hand at song-writing.

At the age of just 22, the man born Robert Allen Zimmerman had taken poetry off the bookshelves and placed it on the jukebox. And what poetry! “A Hard Rain”, written as the 1962 Cuban missile crisis unfolded, compresses innumerable song ideas, written in 10-cent notebooks in Village coffehouses. “I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put them in to this one,” Dylan explained, of a song in whose lyrics can be discerned echoes of Eliot, Lorca, Rimbaud, Ginsberg and many besides. It’s Dylan’s own nightmare war vision: Picasso’s Guernica set to music. “A Hard Rain” inspired a young Canadian poet named Leonard Cohen to try his hand at song-writing.

Those still perplexed by the very idea of Bob Dylan, Nobel Laureate, should go back to those great 1960s albums – in particular, the trilogy of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde – and to Blood On the Tracks (1975), his last truly great album, one suffused with the pain of love gone bad, to understand why he deserves it. The imagery, the symbolism; the metaphor and allusion; the rhyme and half-rhyme; the assonance and dissonance; the collision of the ordinary and the extraordinary… There’s no doubt that Dylan is a poet and one whose work will be listened to, and read, hundreds of years from now. Shelton would have been thrilled by the Nobel but perhaps not surprised. And he would certainly have been vindicated!

Robert’s belief in Dylan was steadfast. He saw him as one of the 20th century’s great shape-shifting figures, a genius to be spoken of in the same breath as Shaw, Picasso, Welles or Brando. That he didn’t live to see the resurgence of interest in the 1960s or the return to form of the singer-songwriter who defined them is a tragedy. He’d have loved Rough and Rowdy Ways, loved the fact that it was snuck out with the world in lockdown, Dylan’s first original album in almost a decade. On it, he sings “I Contain Multitudes”, a line from Walt Whitman, who hung out Greenwich Village a hundred years before Dylan hit town. Robert used to quote the words of an old Woodstock friend, Bernard Paturel: “There’s so many sides to Dylan he’s round”. Now here’s Dylan’s acknowledgment of that.

While his greatest gift may be his poetic facility, Dylan’s legacy is most apparent in the work of the legions of “composers” who endeavour to create intelligent, meaningfully emotive rock songs to be sung with a drummer nearby, emphasizing the downbeat. As Robert Shelton wrote in “Trust Yourself,” an essay published five years after his original book and included in The Dylan Companion: “Dylan could have died in 1966, or after, and still have changed the face of popular music, and its metabolism.”

A self-described “musical expeditionary,” Bob Dylan will surely play on until his final breath, like the old bluesmen he so reveres. Like Dylan Thomas, who took his last drink at the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village, a decade before Bob Dylan, the Clancy Brothers and Robert Shelton propped up the bar, he himself will “rage against the dying of the light.”

A self-described “musical expeditionary,” Bob Dylan will surely play on until his final breath, like the old bluesmen he so reveres. Like Dylan Thomas, who took his last drink at the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village, a decade before Bob Dylan, the Clancy Brothers and Robert Shelton propped up the bar, he himself will “rage against the dying of the light.”

The fierce glow of his songs will never be extinguished and anyone wanting to understand the 20th century needs to pay attention to them.

Happy birthday, Bob. May your song always be sung – and may you stay forever young.

- Bob Dylan: No Direction Home by Robert Shelton, illustrated edition with a new foreword and afterword by Elizabeth Thomson, is published by Palazzo Editions in the UK and Sterling Publishing in the US

Add comment