Patriots Day is a patriots’ film. It dramatises the grievous day on which American values were threatened on American soil like no other time since 9/11. Two bombs were detonated at the Boston marathon in April 2013: two bystanders were killed, 16 lost limbs while two policemen would go on to lose their lives. The two terrorists of Chechen origin who planted the bombs were hunted down by Boston police and the FBI until the streets were once more safe.

How to put a human face on a story with so many disparate elements? The opening sequences carefully introduce us to the various individuals whose lives, you sense with grim foreboding, will be irrevocably altered or even terminated by the day’s events: a lonely Chinese student, a sweet shy cop, a young married couple on whose lithe, soon-to-be-amputated limbs the camera lingers as they make love. (Pictured below: Rachel Brosnahan and Christopher O'Shea as Jessica Kensky and Patrick Downes.)

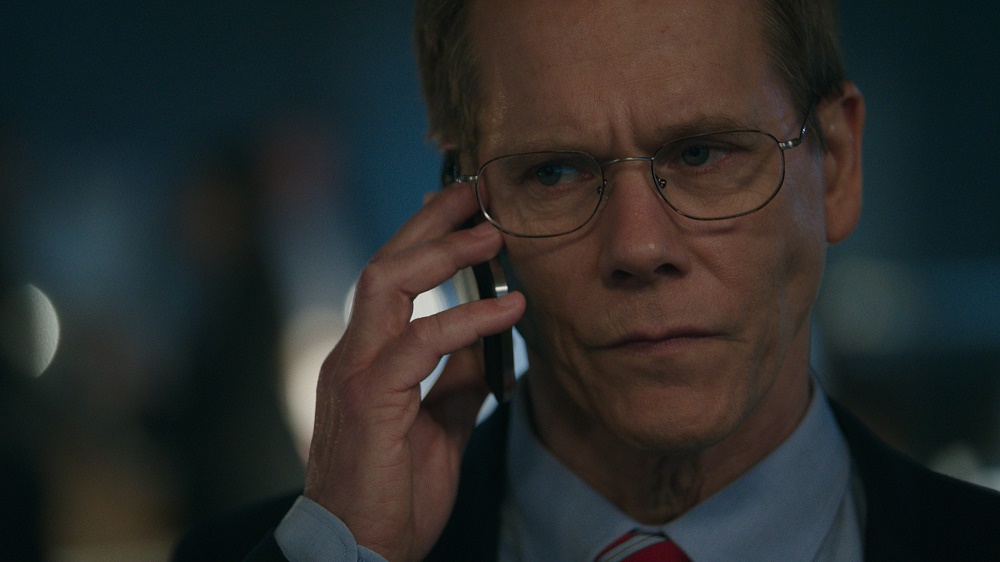

The script also chooses to zoom in on the domestic lives of the Tsarnaev brothers, the perpetrators of the atrocity. The older brother Tamerlan has a wife and a small child, and is clearly of a more ideological bent. “[Martin Luther] King was a fornicator,” he sneers. “But I’m a fornicator,” reasons his doubting kid brother Dzhokhar, who has a penchant for videogames and fast cars. But the main focus, the glue holding the centre together, is fictional police sergeant Tommy Saunders (Mark Wahlberg), a fast-talking maverick who is just back in uniform after a period of suspension. He wears a knee brace and suffers the ribbing of colleagues but is essentially the huggable spirit of dauntless, decent Boston made flesh. He’s stationed closest to the bombing and, as the injured writhe and groan on the sidewalk, is at the heart of the police effort to clear the route of runners and allow ambulances in. Later, when the bigwigs of the Bureau (headed by Kevin Bacon) want to know how to locate the perpetrators on many hours of CCTV footage, they rely heavily on his matchless local knowledge.

The script also chooses to zoom in on the domestic lives of the Tsarnaev brothers, the perpetrators of the atrocity. The older brother Tamerlan has a wife and a small child, and is clearly of a more ideological bent. “[Martin Luther] King was a fornicator,” he sneers. “But I’m a fornicator,” reasons his doubting kid brother Dzhokhar, who has a penchant for videogames and fast cars. But the main focus, the glue holding the centre together, is fictional police sergeant Tommy Saunders (Mark Wahlberg), a fast-talking maverick who is just back in uniform after a period of suspension. He wears a knee brace and suffers the ribbing of colleagues but is essentially the huggable spirit of dauntless, decent Boston made flesh. He’s stationed closest to the bombing and, as the injured writhe and groan on the sidewalk, is at the heart of the police effort to clear the route of runners and allow ambulances in. Later, when the bigwigs of the Bureau (headed by Kevin Bacon) want to know how to locate the perpetrators on many hours of CCTV footage, they rely heavily on his matchless local knowledge.

Despite a real-life coda, this is no documentary reconstruction but a macho hybrid fashioning entertainment from tragedy. The tropes are familiar from disaster movies. “What do you need?” Kevin Bacon is asked. “A command centre,” he says. “A really big one.” (Watch clip overleaf) Cut to a vast warehouse soon cluttered with operatives at monitors. Rugged wit has been parachuted in to help lighten the script. JK Simmons's no-nonsense police officer has a humorous hint of Clint about him. There are laughs in the younger Tsarnaev’s desire for a Bluetooth connection in a carjacked SUV. Even the climactic shoot-out has its frothier moments.

Director Peter Berg licks the story along at an efficient pace, imparts a powerful sense of a city under siege in the overhead camerawork, and wrings tears in a final reveal involving the actual participants. Dramatically, though, for all the immense effort of the manhunt, not quite enough is at stake in Patriots Day. There is some alpha dog dick-waving between the FBI and John Goodman's police commissioner (“this is my fucking city,” he hollers). And that's about it.

Director Peter Berg licks the story along at an efficient pace, imparts a powerful sense of a city under siege in the overhead camerawork, and wrings tears in a final reveal involving the actual participants. Dramatically, though, for all the immense effort of the manhunt, not quite enough is at stake in Patriots Day. There is some alpha dog dick-waving between the FBI and John Goodman's police commissioner (“this is my fucking city,” he hollers). And that's about it.

Deep down this is civic hagiography in which America is on the side of the angels. The script is disinclined to interrogate the motivations, however fanatical, of its home-grown jihadists. In just one brief powerful face-off, Tamerlan’s wife is interviewed by an inscrutable woman posing as a devout Muslim. The film’s most dismal biorhythmic low finds Wahlberg muttering a climactic homily about love conquering hate and good evil. It’s a pity that this worthy memorial, which arrives at a loaded moment in America’s relationship with Islam, is more interested in redemption than nuance. Why doesn't Berg do something really useful and make a film about the mass murders caused by the US's slack laws on gun ownership?

Overleaf: 'It's terrorism.' Watch a clip from Patriots Day

While Katherine makes herself increasingly crucial to an initially hostile set of colleagues

While Katherine makes herself increasingly crucial to an initially hostile set of colleagues

It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe).

It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe). The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.

The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.

There are intriguing, contrasting perspectives on love here – and on the consequences when it breaks down. But Har’el seems reluctant to trust her subjects’ stories much, or even to tell them in a particularly clear or straightforward way. Instead, she seems to want to get inside her protagonists’ heads, to see the world from their individual perspectives – which might not give us many insights into love, even if it makes for some unforgettable visuals.

There are intriguing, contrasting perspectives on love here – and on the consequences when it breaks down. But Har’el seems reluctant to trust her subjects’ stories much, or even to tell them in a particularly clear or straightforward way. Instead, she seems to want to get inside her protagonists’ heads, to see the world from their individual perspectives – which might not give us many insights into love, even if it makes for some unforgettable visuals. Har’el’s blurring of fact and fiction, though not a new trick, is one of the film’s most fascinating conceits – and also one of its most troublesome. It’s fine when we know what we’re watching isn’t real – as in Willie’s elaborately choreographed underwater skirmish with (supposedly) his love rival (pictured above), which his story builds to. But at other times, truth and fictions are considerably less easy to tell apart – as in New Yorker John’s strange appearance on a cable TV channel, expounding his theories on love.

Har’el’s blurring of fact and fiction, though not a new trick, is one of the film’s most fascinating conceits – and also one of its most troublesome. It’s fine when we know what we’re watching isn’t real – as in Willie’s elaborately choreographed underwater skirmish with (supposedly) his love rival (pictured above), which his story builds to. But at other times, truth and fictions are considerably less easy to tell apart – as in New Yorker John’s strange appearance on a cable TV channel, expounding his theories on love. But for all the visual cleverness, the garish colours and the dreamlike connections, the stories Har’el is telling just don’t end up seeming that interesting – or at least she doesn’t probe them strongly enough to discover much empathy. By the end of LoveTrue, we don’t get to know (and therefore care) much about any of her trio of protagonists – are they there simply because they’re a bit kooky? In any case, Har’el doesn’t seem compelled enough by them to tell their stories simply and sincerely, other than as a framework for her own unbridled imagination. LoveTrue is a thoroughly entertaining and stylish 80 minutes of cinema, but whether it shines any new light on one of life’s great mysteries – well, that’s another matter entirely.

But for all the visual cleverness, the garish colours and the dreamlike connections, the stories Har’el is telling just don’t end up seeming that interesting – or at least she doesn’t probe them strongly enough to discover much empathy. By the end of LoveTrue, we don’t get to know (and therefore care) much about any of her trio of protagonists – are they there simply because they’re a bit kooky? In any case, Har’el doesn’t seem compelled enough by them to tell their stories simply and sincerely, other than as a framework for her own unbridled imagination. LoveTrue is a thoroughly entertaining and stylish 80 minutes of cinema, but whether it shines any new light on one of life’s great mysteries – well, that’s another matter entirely.

Living in Hell’s Kitchen in the late Eighties, I collected my own set of memories: a waif-like teen prostitute flagging down trucks outside my apartment house on 46th Street each lunchtime for weeks on end; spent condoms in the gutters; being stalked by the six-foot hustler I rebuffed on 42nd the only time I walked down the street at 1am. Hundreds of mentally ill and homeless people lived locally. It wasn’t simply a red-light district; it was a well of illness and pain.

Living in Hell’s Kitchen in the late Eighties, I collected my own set of memories: a waif-like teen prostitute flagging down trucks outside my apartment house on 46th Street each lunchtime for weeks on end; spent condoms in the gutters; being stalked by the six-foot hustler I rebuffed on 42nd the only time I walked down the street at 1am. Hundreds of mentally ill and homeless people lived locally. It wasn’t simply a red-light district; it was a well of illness and pain. Taxi Driver’s undiminished power owes partially to Scorsese’s harnessing of Michael Johnson’s restless camerawork, with its ominous pans and tracking shots, and

Taxi Driver’s undiminished power owes partially to Scorsese’s harnessing of Michael Johnson’s restless camerawork, with its ominous pans and tracking shots, and  In 1981, Travis inspired John Hinckley Jr, who wanted to impress Foster, to try to assassinate President Reagan. Taxi Driver thus acquired an undeserved notoriety. Blaming the film as the root cause of Hinckley’s act is akin to blaming it for Arthur Bremer’s 1972 shooting of George Wallace (Schrader read Bremer’s diaries before writing the script) or for Samuel Byck’s assassination attempt on President Nixon in 1974 (Schrader says he based “Bickle” on a radio show called The Bickersons, not “Byck”), which generated the 2004 Sean Penn film The Assassination of Richard Nixon.

In 1981, Travis inspired John Hinckley Jr, who wanted to impress Foster, to try to assassinate President Reagan. Taxi Driver thus acquired an undeserved notoriety. Blaming the film as the root cause of Hinckley’s act is akin to blaming it for Arthur Bremer’s 1972 shooting of George Wallace (Schrader read Bremer’s diaries before writing the script) or for Samuel Byck’s assassination attempt on President Nixon in 1974 (Schrader says he based “Bickle” on a radio show called The Bickersons, not “Byck”), which generated the 2004 Sean Penn film The Assassination of Richard Nixon.