Oscars 2012: Meryl and Woody - Gongs and Noms | reviews, news & interviews

Oscars 2012: Meryl and Woody - Gongs and Noms

Oscars 2012: Meryl and Woody - Gongs and Noms

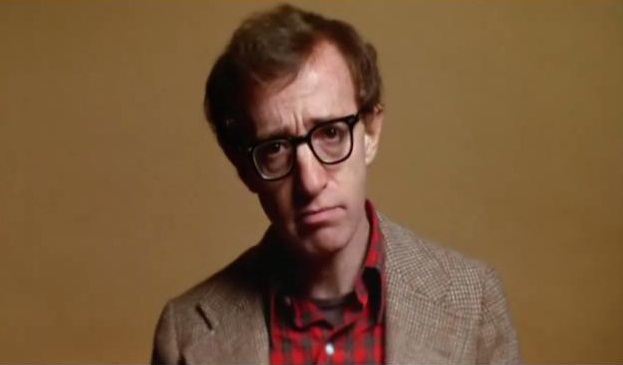

They're Oscar royalty with 40 nominations and seven Academy Awards between them. We assess two remarkable movie careers

They have been racking up the Oscar nominations since 1978, and this year they were back.

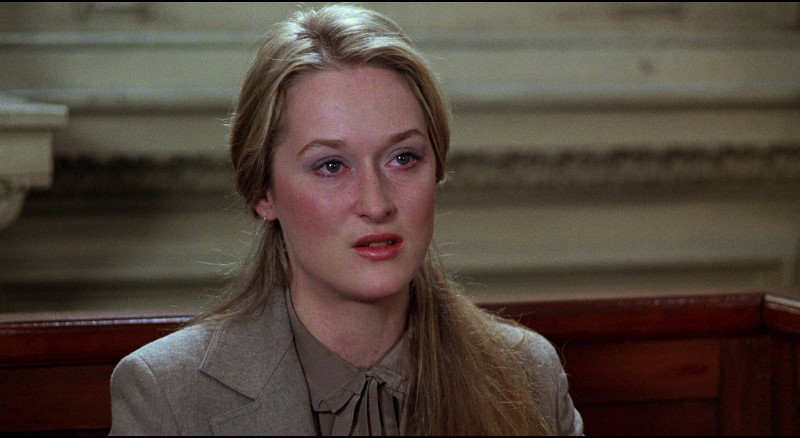

The Academy’s most nominated (if we discount composers and technicians) have been on screen together in only one film, as an estranged husband and wife in Manhattan (she had run off with a woman). They shared a different kind of disappointment in 1988, both losing in their categories to Moonstruck. Those intersections aside, they could not be more different. Where Streep is never remotely the same from film to film, disappearing behind costumes, wigs and above all accents, Allen the actor and director and, even to an extent, scriptwriter has stuck rigidly to the same familiar comic-romantic furrow. (He also doesn't turn up to collect his gongs.) But what is striking about both of their careers is the sheer consistency of a notoriously conservative Academy’s love for them.

For clarity, our listings refer to the year the ceremony was held rather than the year of film under adjudication. Thus Midnight in Paris and The Iron Lady are nominated at the 84th Academy Awards for achievements in film in 2011. theartsdesk's film writers have divided up into two teams to take an Oscarological overview of the films which attracted the attention of the Academy. Batting for Streep are Veronica Lee, Demetrios Matheou, Jasper Rees and Matt Wolf. Allen's backers are Emma Dibdin, Graham Fuller, Emma Simmonds and Adam Sweeting. We also tell you who they lost to, and some of those results are even more shocking now than they will have seemed at the time.

1978

WOODY'S GONGS: Annie Hall, best director, best screenplay with Marshall Brickman

Woody’s noms: Annie Hall, best actor (lost to Richard Dreyfuss, The Goodbye Girl)

Woody’s noms: Annie Hall, best actor (lost to Richard Dreyfuss, The Goodbye Girl)

Ingeniously directed, sublimely scripted and beautifully performed (Diane Keaton deservedly claimed Best Actress and Allen too is terrific), Annie Hall is a romance as only Woody can make ‘em. 1978’s Best Picture is a perfect balance of Allen’s comedic intellectualism, light directorial touch and idiosyncratic insight: “A relationship is like a shark: it has to constantly move forward or it dies. I think what we’ve got on our hands is a dead shark”. ES

1979

Meryl’s nom: The Deer Hunter, best supporting actress (lost to Maggie Smith, California Suite)

Meryl’s nom: The Deer Hunter, best supporting actress (lost to Maggie Smith, California Suite)

Michael Cimino's best film tapped epically into American anxiety about Vietnam. This was mostly an actors' picture for Pittsburgh factory workers played by Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken and John Savage. Streep sweetly plays Linda, Walken's girlfriend who has a bereft kind of intimacy with De Niro when he returns home alone. JR

Woody's noms: Interiors, best director (lost to Robert Benton, Kramer vs Kramer), best screenplay (lost to Coming Home)

Sandwiched between a comic masterpiece and a serio-comic one, Allen’s somber Bergmanesque drama about a clinically depressed woman (Geraldine Page), newly abandoned by her husband, and their three self-indulgent grown-up daughters divided the critics and dismayed his following. Yet it’s a remarkably beautiful, psychologically accurate film, the precise, chilly mise-en-scène perfectly capturing the emotional sterility at the family’s heart. The shot of Diane Keaton, Mary Beth Hurt, and Kristin Griffith at the window is indelible. GF

Sandwiched between a comic masterpiece and a serio-comic one, Allen’s somber Bergmanesque drama about a clinically depressed woman (Geraldine Page), newly abandoned by her husband, and their three self-indulgent grown-up daughters divided the critics and dismayed his following. Yet it’s a remarkably beautiful, psychologically accurate film, the precise, chilly mise-en-scène perfectly capturing the emotional sterility at the family’s heart. The shot of Diane Keaton, Mary Beth Hurt, and Kristin Griffith at the window is indelible. GF

1980

MERYL'S GONG: Kramer vs Kramer, best supporting actress

MERYL'S GONG: Kramer vs Kramer, best supporting actress

It was a courageous decision to take on the part of Joanna Kramer, who walks out on her husband and five-year-old son, then returns 18 months later demanding custody. But if the sympathy in this superior weepie was weighted in favour of trainee dad Dustin Hoffman, Streep’s nuanced performance kept us from dismissing her character as a cold-hearted villainess. Despite scant screen time, she deserved the win. DM

Woody’s noms: Manhattan, best screenplay (with Marshall Brickman) (lost to Breaking Away)

Woody’s noms: Manhattan, best screenplay (with Marshall Brickman) (lost to Breaking Away)

It’s rather sad that one of Allen’s bittersweet best walked away from the 1980 ceremony empty-handed (Mariel Hemingway also lost out in the Best Supporting Actress category, to none other than Meryl). Allen captures NYC’s majesty and minutiae in gorgeous monochrome, while his superb screenplay (co-written with Marshall Brickman) gives us odd couplings, romantic disillusionment and pithy wisdom: “I think people should mate for life – like pigeons, or Catholics.” It was robbed. ES

1981

Meryl’s nom: The French Lieutenant’s Woman, best actress (lost to Katharine Hepburn, On Golden Pond)

Streep went British (as she would later do several times over, of course) in Karel Reisz’s elegant film version of John Fowles’s novel, from which point the quay at Lyme Regis has never looked quite the same again. Appearing both as a cloaked governess called Sarah Woodruff and as Anna, the modern-day actress playing her, Streep was at once enigmatic, beautiful, and alluring – as befits a script by Harold Pinter. Now if only she had found room/time to play Emma in his play Betrayal on stage or screen! MW

Streep went British (as she would later do several times over, of course) in Karel Reisz’s elegant film version of John Fowles’s novel, from which point the quay at Lyme Regis has never looked quite the same again. Appearing both as a cloaked governess called Sarah Woodruff and as Anna, the modern-day actress playing her, Streep was at once enigmatic, beautiful, and alluring – as befits a script by Harold Pinter. Now if only she had found room/time to play Emma in his play Betrayal on stage or screen! MW

1983

MERYL'S GONG: Sophie’s Choice, best actress

MERYL'S GONG: Sophie’s Choice, best actress

Such was Streep’s facility as the Eighties developed that it became de rigueur to suggest that she was all shallows, a jumble of tics and accents. Sophie’s Choice, her first win as Best Actress, was a divisive performance but as a Jewish refugee in America who survived the Holocaust, Streep’s vulnerability was translucent. The choice referred to in the title of William Styron’s novel - which child to send to the gas chamber. JR

1984

Meryl’s nom: Silkwood, best actress (lost to Shirley MacLaine, Terms of Endearment)

Meryl’s nom: Silkwood, best actress (lost to Shirley MacLaine, Terms of Endearment)

Sandwiched between two of her most rarefied characters, in Sophie’s Choice and Out of Africa, Streep’s performance as the real-life Karen Silkwood reminded us of the less showy side of her immersive powers. The star disappeared entirely into the role of the blue collar woman who died, mysteriously, while exposing heath and safety issues at her nuclear power plant. DM

1985

Woody’s nom: Broadway Danny Rose, best director (lost to Miloš Forman, Amadeus), best screenplay (lost to Places in the Heart)

Woody’s nom: Broadway Danny Rose, best director (lost to Miloš Forman, Amadeus), best screenplay (lost to Places in the Heart)

Couched as an anecdote shared by comedians over lunch at Manhattan’s Carnegie Deli, Broadway Danny Rose acquires a mythical quality as it tells, in flashback, the story of a hopeless showbiz agent (Allen) with unmarketable clients who finds himself on the run when he’s thrown together with a gangster’s ex-moll (Mia Farrow). It’s not only Allen’s most tender romance, but a unique tribute to kindness. GF

1986

Meryl’s nom: Out of Africa, best actress (lost to Geraldine Page, The Trip to Bountiful)

Meryl’s nom: Out of Africa, best actress (lost to Geraldine Page, The Trip to Bountiful)

Streep once had a faaarm in Africa. In this adaption of Karen Blixen’s memoir about a Danish woman intrepidly running a plantation in Kenya, the actress’s most notorious accent – all elongated vowels - found itself competing with beautifully shot landscapes (Sydney Pollack directed). Robert Redford drifted in and out much as Blixen’s real-life Etonian lover once did, only with more blond hair. Admired at the time, in retrospect it looks as if Streep took her taste for romantic masochism too far with this one. JR

Woody’s nom: The Purple Rose of Cairo, best screenplay (lost to Witness)

Woody’s most unashamedly romantic film sees him toning down the cynicism (it’s no coincidence that there’s no Woody, or Woody substitute, onscreen) in favour of charming fantasy. Cute and compact, it works far better than the similarly fantastical Midnight in Paris. It’s not, however, dramatically or comedically his most striking screenplay, with a few notable exceptions: “You can’t learn to be real - it’s like learning to be a midget”. ES

Woody’s most unashamedly romantic film sees him toning down the cynicism (it’s no coincidence that there’s no Woody, or Woody substitute, onscreen) in favour of charming fantasy. Cute and compact, it works far better than the similarly fantastical Midnight in Paris. It’s not, however, dramatically or comedically his most striking screenplay, with a few notable exceptions: “You can’t learn to be real - it’s like learning to be a midget”. ES

1987

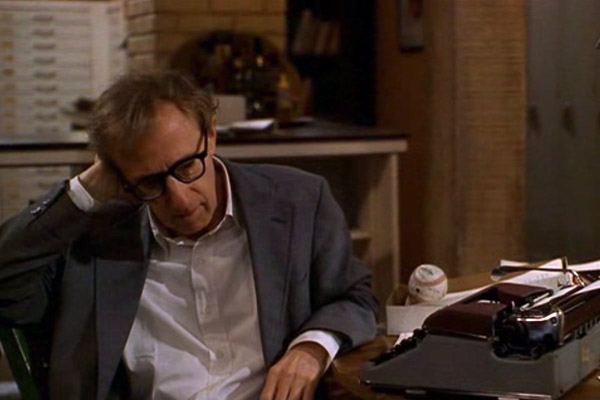

WOODY'S GONG: Hannah and Her Sisters, best screenplay

Woody’s nom: Hannah and Her Sisters, best director (lost to Oliver Stone, Platoon)

Woody’s nom: Hannah and Her Sisters, best director (lost to Oliver Stone, Platoon)

A shrewd web of interconnected stories centred on a middle-class Manhattan family, this is Allen in his neurotically comedic, quietly heartbreaking element. Michael Caine and Dianne Wiest scooped thoroughly justified supporting gongs, while Allen’s deadpan script spins gold for every character from major to minor. Two cases in point are Lee’s misanthropic husband Frederick, and Mickey’s father: “How the hell do I know why there were Nazis? I don’t even know how the can opener works.” ED

1988

Meryl’s nom: Ironweed, best actress (lost to Cher, Moonstruck)

Meryl’s nom: Ironweed, best actress (lost to Cher, Moonstruck)

Meryl Streep roughed it, playing a Depression-era derelict in Hector Babenco’s determinedly grim adaptation of the Pulitzer prize-winning novel by William Kennedy. One pretty much solely for Streep completists, the film saw Streep lose the 1987 Oscar for Best Actress to Moonstruck star Cher, who of course had first made her mark on screen opposite Streep in Silkwood four years before. That scenario could well be repeated this year if Streep’s Oscar-nominated colleague from Doubt, Viola Davis, ends up pipping her to the post this time round for Best Actress. MW

Woody's nom: Radio Days, best original screenplay (lost to Moonstruck)

John Patrick Shanley won 1988's screenplay Oscar for Moonstruck, which was like giving it to the sorcerer's apprentice. Twenty-four years later, Woody's hilarious, acerbic and poignant effort for Radio Days glitters ever brighter, with its rumbustious cast of characters from 1940s Rockaway, NJ and its evocation of a childhood infatuation with the magical world of the wireless, where words spoke louder than pictures. Mia Farrow's elocution lessons and the burglars who win a phone-in competition were among its many delights. AS

John Patrick Shanley won 1988's screenplay Oscar for Moonstruck, which was like giving it to the sorcerer's apprentice. Twenty-four years later, Woody's hilarious, acerbic and poignant effort for Radio Days glitters ever brighter, with its rumbustious cast of characters from 1940s Rockaway, NJ and its evocation of a childhood infatuation with the magical world of the wireless, where words spoke louder than pictures. Mia Farrow's elocution lessons and the burglars who win a phone-in competition were among its many delights. AS

1989

Meryl’s nom: A Cry in the Dark, best actress (lost to Jodie Foster, The Accused)

Streep took on an Australian accent (and rather severe black wig) to illuminate the real-life story of Lindy Chamberlain, who was accused of the murder of her nine-week-old daughter despite the parents’ insistence that the baby was carried off by a dingo one fateful August night in 1980; Sam Neill played her husband. Herself the mother of three daughters (and a son), Streep gave off a mesmeric, slightly forbidding intensity in a part that reunited the star with her director on Plenty, Fred Schepisi. The New York Times in their review of the film called Streep “incomparable” – the adjective that more than any other has been applied to this actress over time. MW

Streep took on an Australian accent (and rather severe black wig) to illuminate the real-life story of Lindy Chamberlain, who was accused of the murder of her nine-week-old daughter despite the parents’ insistence that the baby was carried off by a dingo one fateful August night in 1980; Sam Neill played her husband. Herself the mother of three daughters (and a son), Streep gave off a mesmeric, slightly forbidding intensity in a part that reunited the star with her director on Plenty, Fred Schepisi. The New York Times in their review of the film called Streep “incomparable” – the adjective that more than any other has been applied to this actress over time. MW

1990

Woody’s noms: Crimes and Misdemeanors, best director (lost to Oliver Stone, Born on the Fourth of July), best screenplay (lost to Dead Poets Society)

Another gongless night for Woody, but Crimes and Misdemeanors rates as one of his funniest yet darkest hours. A masterful synthesis of satire, murder story and profound moral meditation, it's like an index of Allen's inner universe as he explores the hypocritical world of ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), denizen of Manhattan's Jewish upper middle class. Allen's own performance as Cliff, gloomy maker of unpopular documentaries, is scalpel-sharp, and Alan Alda is a treat. AS

Another gongless night for Woody, but Crimes and Misdemeanors rates as one of his funniest yet darkest hours. A masterful synthesis of satire, murder story and profound moral meditation, it's like an index of Allen's inner universe as he explores the hypocritical world of ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), denizen of Manhattan's Jewish upper middle class. Allen's own performance as Cliff, gloomy maker of unpopular documentaries, is scalpel-sharp, and Alan Alda is a treat. AS

1991

Meryl’s nom: Postcards from the Edge, best actress (lost to Kathy Bates, Misery)

Meryl’s nom: Postcards from the Edge, best actress (lost to Kathy Bates, Misery)

In Carrie Fisher's barely disguised and very funny autobiography (directed with panache by Mike Nichols), Streep is washed-up Hollywood star and substance abuser Suzanne Vale, who moves back home – Shirley MacLaine, doing an equally memorable comic turn as her gin-soaked mom. Cue mother-daughter rivalry on a heroic scale. Streep was unlucky to lose for a stellar performance. VL

Woody’s nom: Alice, best screenplay (lost to Ghost)

Woody’s nom: Alice, best screenplay (lost to Ghost)

Although it’s impossible to know exactly why this Mia Farrow vehicle never rose above the ranks of minor Woody, it’s easy to hazard a guess. Farrow’s character, an affluent housewife blighted by ennui, is a difficult character to empathise with, lacking either a defined personality or an engaging emotional plight. Allen’s never had difficulty making flawed protagonists sympathetic – his mistake here was to assume the audience would be as inherently entranced by Farrow as he was. ED

1993

Woody’s nom: Husbands and Wives, best screenplay (lost to The Crying Game)

Woody’s nom: Husbands and Wives, best screenplay (lost to The Crying Game)

It’s impossible to look at this – a multi-stranded drama that sees Allen’s character set his sights on a teenage student as his marriage to Mia Farrow crumbles – without the black cloud of real life scandal threatening to overshadow the work. But it’s worth resisting the impulse to project, because this is some of Allen’s most subtly observed scripting: acerbic, incisive and unusually bleak. All of the above considered, it’s a miracle he was nominated at all. ED

1995

Woody’s nom: Bullets over Broadway, best director (lost to Robert Zemeckis, Forrest Gump), best screenplay with Douglas McGrath (lost to Pulp Fiction)

Woody’s nom: Bullets over Broadway, best director (lost to Robert Zemeckis, Forrest Gump), best screenplay with Douglas McGrath (lost to Pulp Fiction)

Allen’s most recent Best Director nod until this year’s for Midnight in Paris also marked the first time he deemed himself “too old” for the lead, enlisting John Cusack to play the struggling artist proxy in much the same vein as Owen Wilson later would. It’s Bullets’ deft, pitch-black script you remember most, but Allen’s masterful handling of his ensemble cast in their seven-hander scenes shouldn’t be underestimated, least of all in favour of Forest Gump. ED

1996

Meryl’s nom: The Bridges of Madison County, best actress (lost to Susan Sarandon, Dead Man Walking)

Meryl’s nom: The Bridges of Madison County, best actress (lost to Susan Sarandon, Dead Man Walking)

The plot of Robert James Waller’s novel has a pulpy feel, but that is ruthlessly stripped out in the hands of Streep and Clint Eastwood, who also directed. As a farmer's wife given a sudden shot at romantic fulfilment when an itinerant photographer drifts through town just as her family are away, Streep is haunting in an underrated autumnal tragedy about the life not lived. In what can be seen as the relative drought of the 1990s, this was her finest hour as she entered her middle years. JR

Woody’s nom: Mighty Aphrodite, best screenplay (lost to The Usual Suspects)

Woody’s nom: Mighty Aphrodite, best screenplay (lost to The Usual Suspects)

Mighty Aphrodite is rescued from (relative) mediocrity by Mira Sorvino’s Judy Holliday-esque turn as a hooker who turns out to be the birth mother of Allen’s adopted son. Although the screenplay contains a smattering of zingers (“You’ve got no confidence, I like that in a man”), it’s hardly vintage Allen and was never going to trouble eventual Original Screenplay winner The Usual Suspects. Sorvino on the other hand bested the pack to take the Best Supporting Actress gong. ES

1998

Woody’s nom: Deconstructing Harry, best screenplay (lost to Good Will Hunting)

Woody’s nom: Deconstructing Harry, best screenplay (lost to Good Will Hunting)

Whether you believe this story about a novelist who “can’t function in life, but he can in art” is about Allen himself or not, there’s surprisingly little to recommend its brand of mean-spirited character study. It’s a clear progression from the raw, bleak streak that ran through Husbands and Wives, but an altogether more cynical and less memorable venture, bordering at times on needlessly vicious. Good Will Hunting, an impressive achievement from first-time scripters, was the deserving victor. ED

1999

Meryl’s nom: One True Thing, best actress (lost to Gwyneth Paltrow, Shakespeare in Love)

Meryl’s nom: One True Thing, best actress (lost to Gwyneth Paltrow, Shakespeare in Love)

Streep's often forgotten movie (the basis of a great pub quiz question then), this was a melodrama directed by Carl Franklin about a mother in a bookish family who are, however, barely literate emotionally. As she lies dying from cancer, she gives some important life lessons to daughter Renée Zellweger. In a middling year, the gong went to her weepiness Gywneth. VL

2000

Meryl’s nom: Music of the Heart, best actress (lost to Hilary Swank, Boys Don’t Cry)

Meryl’s nom: Music of the Heart, best actress (lost to Hilary Swank, Boys Don’t Cry)

An astonishing sidesweep from the schlock-horror merchant Wes Craven to make what's known as an inspirational drama. In an otherwise predictable tug-at-the-heartstrings movie, Streep stands out as a high-school teacher in Harlem who, against the odds and with zero budget, inspires her charges to a love of classical music – a sort of El Sistema for New Yorkers. VL

2003

Meryl’s nom: Adaptation, best supporting actress (lost to Catherine Zeta-Jones, Chicago)

Meryl’s nom: Adaptation, best supporting actress (lost to Catherine Zeta-Jones, Chicago)

Streep was at her most warm and attractive – and unusually sexy – in this typically baroque confection by writer Charlie Kaufman and director Spike Jonze. While Nicolas Cage (playing both Kaufmann and his imaginary brother) and Chris Cooper as a toothless orchid thief took all the high notes, Streep’s journalist offered the emotional ballast. Solid, dependable, a tad over-rewarded with a nomination. DM

2006

Woody’s nom: Match Point, best screenplay (lost to Crash)

Woody’s nom: Match Point, best screenplay (lost to Crash)

Just when it seemed Allen had peaked, he returned with a brilliant, Dostoievskian London noir about a chancer who marries into money, sleeps with his brother-in-law’s girlfriend, then slaughters her when she becomes inconvenient. Where Crimes and Misdemeanors’ mistress-killer escapes conscience intact, this one is left with wealth, wife, and baby, but facing a lifetime of guilt. So the drum-tight Match Point was a moral advance. GF

2007

Meryl’s nom: The Devil Wears Prada, best actress (lost to Helen Mirren, The Queen)

Meryl’s nom: The Devil Wears Prada, best actress (lost to Helen Mirren, The Queen)

Streep showed a fantastically mean streak in David Frankel's teasing snapshot of the absurdity of fashion publishing. Her chilly fashionista is based, so it's assumed, on Anna "Nuclear" Wintour, indestructible editrix of Vogue. She stole the film from under the nose of Anne Hathaway's secretarial ingénue, but no amount of pantomime villainy was going to snitch the gong from Mirren's QEII. JR

2009

Meryl’s nom: Doubt, best actress (lost to Kate Winslet, The Reader)

Meryl’s nom: Doubt, best actress (lost to Kate Winslet, The Reader)

It was hard to ignore Streep’s rum turn as a nun on the warpath, in this so-so adaptation of the Pulitzer-winning play. Her Sister Aloysius patrols a Brooklyn Catholic school like a crow in a cassock, pecking at her charges while setting her sights on the priest she suspects of showing them too much affection. Streep made her character – who condemns Frosty the Snowman for espousing pagan beliefs – at once funny and ludicrous, vulnerable and highly dangerous. But no-one would argue against Winslet’s turn for a gong. DM

2010

Meryl’s nom: Julie & Julia, best actress (lost to Sandra Bullock, The Blind Side)

Meryl’s nom: Julie & Julia, best actress (lost to Sandra Bullock, The Blind Side)

Another tour-de-force impersonation, not of an accent this time but of 1960s celebrity chef Julia Child, which caught to an uncanny degree her distinctive, fluting voice and delivery. Streep's performance in Nora Ephron's film delivered every comic moment her eccentric character offered, but also the underlying pain she felt about being childless. Unlucky loss in a strong year. VL

2012

WOODY'S GONG: Midnight in Paris, best director

WOODY'S GONG: Midnight in Paris, best director

Woody's nom: Midnight in Paris, best director (lost to Michel Haznavicius, The Artist)

Allen's swooning homage to the city by the Seine recalls his cinematic infatuation with Manhattan from three decades earlier, and this sense of his emotional rekindling has made Midnight... the best-received of Allen's recent works, prompting four Oscar nominations. Owen Wilson makes a better-than-expected Woody-proxy as Gil, the screenwriter intoxicated with belle époque Paree, yet feeling the drag of the prosaic present. But even the Carla Bruni cameo could not wrest the Europhile vote from The Artist AS

MERYL'S GONG: The Iron Lady, best actress

MERYL'S GONG: The Iron Lady, best actress

Meryl plays Maggie: The casting promised an event from the minute it was announced, and the results didn’t disappoint, whatever one’s feelings about the director Phyllida Lloyd’s film as a whole (and I liked it more than most). Various others have played Herself on stage and screen, but few with Streep’s mixture of cunning and wit and the gentlest soupçon of sensuality. One question comes to mind: who will possibly play La Meryl when that biopic comes to be made? MW

Share this article

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Our Mothers review - revisiting the horrors of Guatemala's civil war

Hard-hitting first feature from director Cesar Diaz

Our Mothers review - revisiting the horrors of Guatemala's civil war

Hard-hitting first feature from director Cesar Diaz

DVD/Blu-ray: The Holdovers

Bittersweet, beautifully observed seasonal comedy - not just for Christmas

DVD/Blu-ray: The Holdovers

Bittersweet, beautifully observed seasonal comedy - not just for Christmas

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes review - a post-human paradise

A richly suggestive new era for the franchise reconnects with its 1968 start

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes review - a post-human paradise

A richly suggestive new era for the franchise reconnects with its 1968 start

La Chimera review - magical realism with a touch of Fellini

Josh O’Connor excels as an archaeologist turned graverobber in the Italian countryside

La Chimera review - magical realism with a touch of Fellini

Josh O’Connor excels as an archaeologist turned graverobber in the Italian countryside

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger review - the Archers up close

Adoring tribute by Martin Scorsese to British filmmaking legends

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger review - the Archers up close

Adoring tribute by Martin Scorsese to British filmmaking legends

Love Lies Bleeding review - a pumped-up neo-noir

There's darkness on the edge of town in Rose Glass's sweaty, violent New Queer gem

Love Lies Bleeding review - a pumped-up neo-noir

There's darkness on the edge of town in Rose Glass's sweaty, violent New Queer gem

Nezouh review - seeking magic in a war

A movie that looks on the dreamier side of Syrian strife

Nezouh review - seeking magic in a war

A movie that looks on the dreamier side of Syrian strife

Blu-ray: The Dreamers

Bertolucci revisits May '68 via intoxicated, transgressive sex, lit up by the debuting Eva Green

Blu-ray: The Dreamers

Bertolucci revisits May '68 via intoxicated, transgressive sex, lit up by the debuting Eva Green

theartsdesk Q&A: Marco Bellocchio - the last maestro

Italian cinema's vigorous grand old man discusses Kidnapped, conversion, anarchy and faith in cinema

theartsdesk Q&A: Marco Bellocchio - the last maestro

Italian cinema's vigorous grand old man discusses Kidnapped, conversion, anarchy and faith in cinema

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

I.S.S. review - sci-fi with a sting in the tail

The imperilled space station isn't the worst place to be

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

That They May Face The Rising Sun review - lyrical adaptation of John McGahern's novel

Pat Collins extracts the magic of country life in the west of Ireland in his third feature film

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Add comment