“Look at the pictures”, yells apoplectic Senator Jesse Helms as he brandishes a clutch of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, “a known homosexual who died of AIDS”. It's 1989 and Senator Helms is doing his level best to close down an exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s photographs at the Contemporary Arts Centre, Cincinnati and have its director, Dennis Barrie, indicted for obscenity.

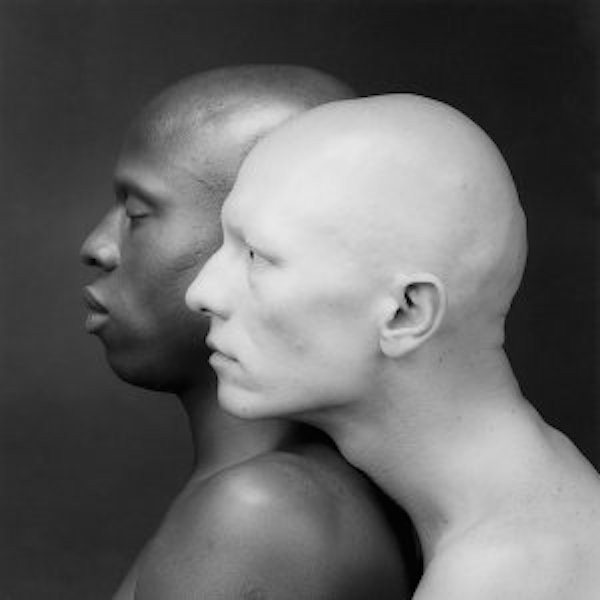

This outpouring in the House of Representatives provides the title and sets the scene for Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, directed by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbarto. We have to wait until the closing shots, though, to discover the outcome of those homophobic ravings; the jury dismissed the indictment and exonerated Mapplethorpe’s work (Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, photographed by Mapplethorpe, below).

Timed to coincide with a retrospective currently on show at the J Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Contemporary Art (LACMA), the film charts Mapplethorpe’s rise from controversial outsider to the darling of the establishment, a transition possibly expedited by the many valuable works gifted to the museums in 2011 by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.The story of the photographer’s life from his childhood to the farewell cocktail party he gave shortly before his untimely death in 1989 is told through talking heads. This tried and tested format would be heavy going if it weren’t for the raunchy nature of the reminiscences, the measured tones of Mapplethorpe’s voice explaining his work and the confrontational beauty of the photographs interspersed with the interviews.

Timed to coincide with a retrospective currently on show at the J Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Contemporary Art (LACMA), the film charts Mapplethorpe’s rise from controversial outsider to the darling of the establishment, a transition possibly expedited by the many valuable works gifted to the museums in 2011 by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.The story of the photographer’s life from his childhood to the farewell cocktail party he gave shortly before his untimely death in 1989 is told through talking heads. This tried and tested format would be heavy going if it weren’t for the raunchy nature of the reminiscences, the measured tones of Mapplethorpe’s voice explaining his work and the confrontational beauty of the photographs interspersed with the interviews.

His sister Nancy recalls their uneventful life in Floral Park, Queens, a suburb of New York City described by Mapplethorpe as “a good place to come from, and a good place to leave”. Their father was a keen amateur photographer, but the young Mapplethorpe showed no interest in it. Later as a student at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn he flunked the photography component of the fine art course, considering it a lesser art form, and passed off his father’s pictures as his own.

Meanwhile, he was living with Patti Smith, who declined to appear in the film, so is present only through the haunting pictures taken of her by Mapplethorpe. They remained friends even after he realised he was gay and began making collages using gay porn before taking his own polaroids.

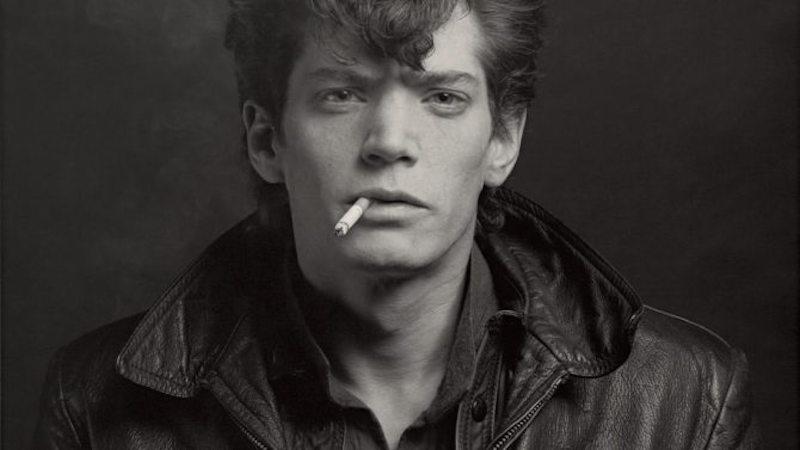

His first male lover, model David Croland, introduced him to the wealthy collector Sam Wagstaff, who bought him a Hasselblad camera, bought him a loft and generously helped him clamber up the slippery pole of success. “He was unbelievably ambitious”, says film-maker Sandy Daley. “He wanted to be a legend.” “Everyone had a crush on him”, recalls writer Fran Lebowitz. “He looked like a ruined cupid, and people hustled him – usually into bed.” He photographed his influential friends and lovers and a pattern soon emerged in which photography became a form of autobiography... ”what I’m involved with at any moment.”

Sex was a major preoccupation. “Sex is the most important thing for me in life”, Mapplethorpe explains. “It offers a bit of magic; but more important are the pictures taken. Art is about opening something up.” He began frequenting The Mine Shaft, an S&M club, and photographing the self-inflicted torture and fetish gear.

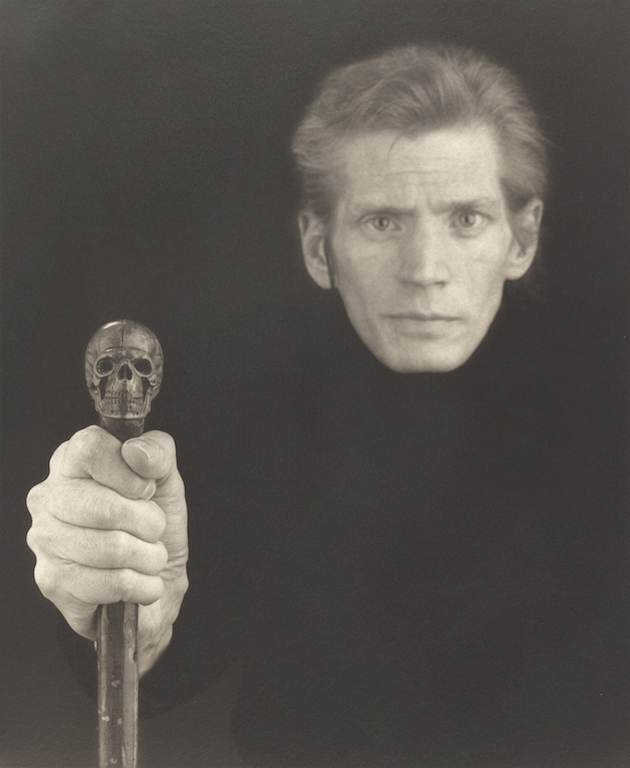

He was brought up a Catholic and one of the most unexpected insights comes from the family priest who likens the whips, crucifixes and blood-letting recorded by Mapplethorpe to a black mass whose imagery derives from its Catholic counterparts. The most moving testament is given by Edward Mapplethorpe, who studied photography and became his brother’s assistant only to be told that, if he wanted to exhibit, he would have to change his name so as not to benefit from his brother’s fame (Self Portrait (With skull cane), below).

The funniest moments are provided by the Getty and LACMA curators whose stated goal is “to humanise Mapplethorpe after the demonisation of the 1990s.” They discuss the aesthetics of startling S&M images such as Self Portrait with Whip. Admiring the way the bull whip snakes towards the edge of the picture and establishes a link between viewer and photographer, they coyly avoid mentioning the fact that the handle is shoved up Mapplethorpe’s arse.

The funniest moments are provided by the Getty and LACMA curators whose stated goal is “to humanise Mapplethorpe after the demonisation of the 1990s.” They discuss the aesthetics of startling S&M images such as Self Portrait with Whip. Admiring the way the bull whip snakes towards the edge of the picture and establishes a link between viewer and photographer, they coyly avoid mentioning the fact that the handle is shoved up Mapplethorpe’s arse.

I interviewed Mapplethorpe in 1983 and remember him as shy, gentle and self-effacing. He made up for his lack of technical expertise by a superb eye for form, a desire for perfection and the ability to elicit great things from his models. “What makes a good photographer is personality”, he told me. “I get something out of people that others don’t. They feel comfortable enough to be whatever they want. A lot of the best ideas come from the models.”

But the film portrays him as a ruthless manipulator obsessed with sex, money and fame. And there’s something relentless about the pace; I came away feeling bludgeoned. By the time of his Whitney retrospective in 1988, Mapplethorpe was reduced by his illness to a living skeleton, and because of the breathtaking scale of his achievements, you assume that he was as ancient as he looked. It's a real shock to be reminded that, when he died the following year, he was only 42.

- Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures is in cinemas from 22 April

Add comment