There is little denying that the Antarctic continent is no longer possessed of the allure that it once was. By all accounts, particularly those unspoken, Antarctica has been betrayed, usurped, eclipsed.

Beyond the sober walls of research laboratories, or the heady enthusiasm of university corridors, people today have scant interest in the icy land mass, twice the size of Australia, on average the coldest, driest, windiest of continents, home to penguins, seals and tardigrades, that 2016 Animal of the Year, though it may be.

What has taken its place? “No single space project... will be more exciting, or more impressive to mankind, or more important.” So claimed US president John F Kennedy, on 25 May 1961, in his Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs. Here, “space” is wanton, surplus; as a mirror to his intent, Kennedy would be better off without it. Because, in the run-up to 1966, a generation weaned on the milk of polar exploration (it was with the Arctic conquered that its opposite truly took hold) gave way to another. For this latter generation, the sum of human ambition would come to be encapsulated in a single sentence, or 11 words, their meaning grumbled about, chewed over ever since: “That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." Did Armstrong Do Bad? Instead of “man”, was it perhaps “a man”? Or the cruel intervention of intergalactic static? The moon in the bag, our scientists, and our scriptwriters, turned ruthlessly to fresher turf; it was two years later that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released Mission Mars (1968).

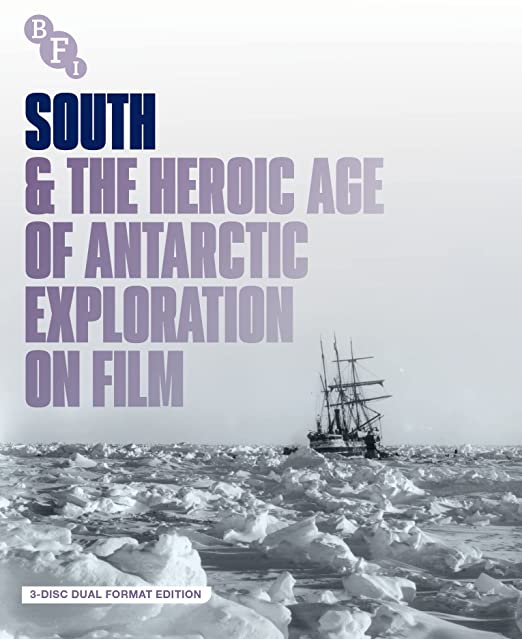

I am not of either generation. Astronauts, as we know them, are passing the way of explorers. Where Ernest Shackleton and Ralph Scott sailed, today Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson soar – common in their privilege, of good education, and wealth, whether inherited or acquired, that has conspired to bestow them with the title celebrity. But the latter are private undertakings, for private rewards. The success or failure of Blue Origin does not weigh upon the collective consciousness, inspiring little-to-nothing of national, nor human pride. It is to imagine a world, quite unlike our own, in which such strength of feeling is possible that we must turn to South, Frank Hurley’s documentary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914-17, painstakingly restored, tinted and toned by BFI technician Brenda Hudson in the 1990s, now remastered digitally.

I am not of either generation. Astronauts, as we know them, are passing the way of explorers. Where Ernest Shackleton and Ralph Scott sailed, today Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson soar – common in their privilege, of good education, and wealth, whether inherited or acquired, that has conspired to bestow them with the title celebrity. But the latter are private undertakings, for private rewards. The success or failure of Blue Origin does not weigh upon the collective consciousness, inspiring little-to-nothing of national, nor human pride. It is to imagine a world, quite unlike our own, in which such strength of feeling is possible that we must turn to South, Frank Hurley’s documentary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914-17, painstakingly restored, tinted and toned by BFI technician Brenda Hudson in the 1990s, now remastered digitally.

South begins with Shackleton’s departure, on 26 October 1914, from amid the thronging port at Buenos Aires, before on-board shots of the crew, their 70-strong company of Canadian sledge dogs, of ice breaking and the shifting floes. Yes, as Briony Dixon writes, this “conformed to the pattern of previous films of the early part of the expedition.” Regardless, the components of narrative are all in attendance. Shackleton is our protagonist, Worsley his sidekick. There is a chorus, or narrator, too: in the intercession of explanatory frames, appropriately penned with a flavour of the upper-class English gentleman, providing such delightful phrases as “Shackleton at the binnacle”, and “Giant Petrels. A most ungainly and quarrelsome species.” We have foreshadowing, in the crab-eater seals, migrating north in advance of the incoming freeze that, unbeknownst to the crew, would be Endurance’s captor and executioner. And there is tragedy in the film. And in what it omits: months of marooning, and the meat of Shackleton’s desperate voyage to South Georgia, tempered only by the relief that Hurley’s spools, submerged in the Weddell Sea, and buried thereafter in the permafrost of Elephant Island, did at long last unveil themselves for broadcast.

Most of us, wishing to view South on the big screen, have missed the chance: the film played at Picturehouses nationwide on 21 February. But this three-disc dual-format edition has a variety of additional archival footage, dug up like cores of Calabrian-stage ice from the depths of the BFI archive. One highlight: footage of Nobu Shirase’s Antarctic Expedition, 1910-1912. In response to the question, “Why film?”, it would be modern of us to suggest that we do so to preserve, immortalise – “quick, before it melts!” Through the patronage of Shunzo Murakami, Shirase’s expedition served a different purpose: fostering a culture of exceptionalism in complement to the rapid industrialisation in the final years of Japan’s Meiji period. And another, a South offcut, for whatever reason deemed unsuitable for the prevailing narrative: on the ice, a game of football (ever-present, it seems, amid events of greater significance). Meanwhile, visible in the background, the Endurance undergoes her slow death, resembling with splintered stern the sad figure of a half-crushed insect.

If theirs was the Heroic Age, how might we define our own? Fearful? Distracted? Apathetic? It is with relief, that we don’t have to; imposing order upon our manifold existence is a prerogative not of the present, but of the future. Hurley knew this. His final frame offers a proclamation: “The doings of these men will be written in history as a glorious epic of the great ice-fields… and will be remembered as long as our Empire exists.” Like the Antarctic, that Empire has dwindled, but the “writing” is yet ongoing. Just as Neil Brand’s musical score successfully amalgamates the fragments of Hurley’s showpiece film into a single chronicle, so the BFI arranges this diverse and miscellaneous footage into a unified and linear collection. In doing so, it gives shape to an idea, vague and sublime, that captivated entire nations, the pursuit of which claimed 19 lives: South.

Add comment