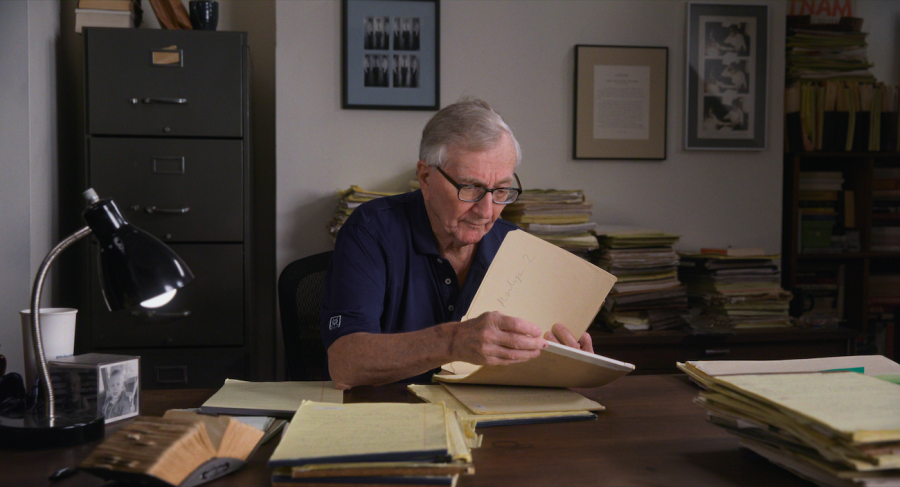

Fierce, unpredictable, complex, cussed, commie. Seymour Hersh would probably admit to all those descriptions of him except the last. Now at last the man who has dominated investigative journalism for 60 years has agreed to be investigated himself for a documentary made by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, 20 years after they first asked him.

One could list the peaks of his career too – My Lai, Watergate, Abu Ghraib – recognising that these names also represent dark lows of modern American history. “Sy”, as he is known, claims that what a reporter personally believes isn’t the point, only what he can find out. His reporting has led him to find out a lot, in all its hideousness, and to be hated for it by many of his fellow countrymen.

One of his rubrics as a journalist is not to get in the way of the story, and this too is the working method of Poitras (director of All the Beauty, about Nan Goldin's fight against the Sackler family), who can be heard lobbing a question at him off-screen from time to time but mainly just lets him talk, without editorialising. His voice is like his reporting: tough, plain-speaking and often terse, not given to embellishment or padding. You come to realise that it is driven by a white-hot anger at what he finds out about his country’s use, and abuse, of power.

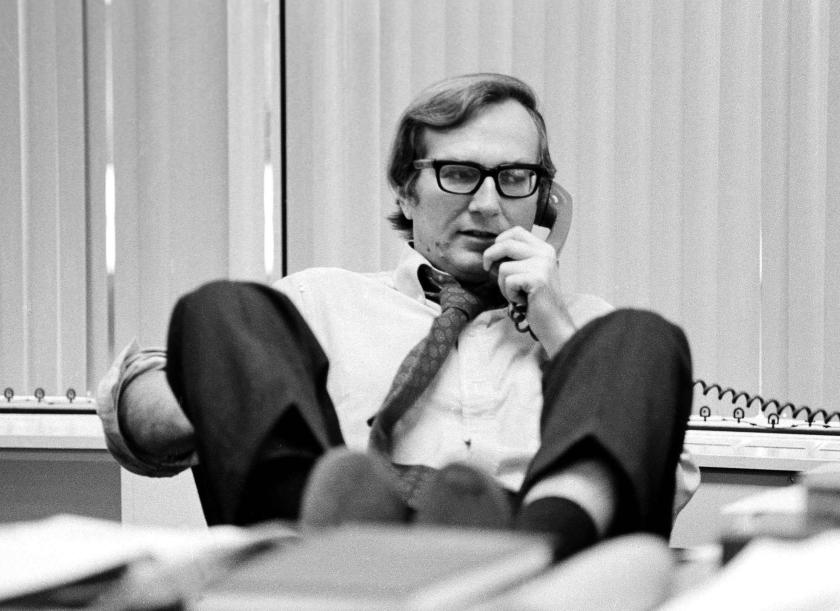

Long before computers and modern telephony, Hersh operated by tireless tracking and casual coaxing of interviewees. (Later In his career he would be accused of yelling at them and coercing them by threatening to spread their secrets on national front-pages.) After finding a job as a police reporter, in Chicago – a kind of gang warfare, cops vs Mob – that he loved, he received a tip that led him to the story of a US Army solder who had gone crazy and killed villagers in Vietnam.

He had uncovered the 1968 My Lai massacre, which claimed hundreds of lives and for which 14 officers were charged, and it seems almost to have undone him. He had a two-year-old son at the time, and the atrocities described to him by the young soldiers involved, especially their accounts of murdering babies and toddlers, sickened him to the point of wanting to quit. Decades later he admits on-camera, his voice choking up for once, that every day he worked on the story was like having 30 years weighing down on his shoulders. He credits his psychiatrist wife Elizabeth for keeping him sane.

William Calley, the initial suspect in the killings, was jailed for life, until a nationwide protest movement, fuelled by the evidence that he was obeying orders to kill the villagers and that the My Lai massacre was not a lone event but a systematic programme for raising the headcount of the dead, was released after a few months. The other officers were charged, Hersh says with a snort, with dereliction of duty and failure to report the incidents; meanwhile, the programme’s instigator, General Westmoreland, was promoted. It was an eye-opening experience for Hersh, his introduction to the art of the cover-up. Soon he was writing about the story behind the story, the way in which officialdom united in denying the truth and proposing “fake news” instead.

Cover-ups have become his stock in trade, from the use, at home, of nerve gas in experiments that killed 6,000 sheep in Utah, the Watergate break-ins and the exploitative practices of Gulf & Western, and then the torturing of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib. His byline was a signal that official skulduggery was being scrutinised. Henry Kissinger hated him, especially when he probed the CIA’s programme of assassinations of left-wing foreign leaders such as Chile’s Allende; Nixon, in his phone calls with Kissinger, called him an SOB (though admitted what he was saying was probably right). Hersh also exposed the CIA’s illicit investigating of US citizens, especially student activists. Heads rolled.

The documentary tracks the way his coverage of these front-page issues eventually made him unclubbable in his own profession. The New York Times held his stories, for as much as two years in one case, presumably hoping they would never run at all. He attracted plaudits from the Washington Post’s Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein for joining them, from the NYT, in investigating Watergate and CREEP. Eventually, though, he and his writing partner, Jeff Gerth, began investigating the corporate ties of the NYT itself. Hersh, who did not like what he found, moved over to freelancing, notably for the New Yorker, and to writing books. Currently, he posts Substack blogs, where he appears to be building a case against individual Israeli army officers for their killing of the citizens of Gaza.

The anomalies of Hersh’s career are mapped out here alongside the victories. It’s intriguing to note, for example, that his biggest scoops, My Lai and Abu Ghraib, needed corroborative photos (preferably colour ones) to be available before magazines would run them. He also admits he regularly breaks a key rule of journalism in relying on single sources. These lone voices, he points out, are usually telling the truth, and ignoring them would mean the stories never surfaced at all. In other respects he is a scrupulous professional, getting angry with the film-makers when he thinks they are going to reveal the identities of his confidential sources.

If the film has a flaw it's that there is too much here for one, two-hour documentary to cover. What it brings is the living presence of the reporter, now in his late eighties, and some of the sources who assisted him. They are sobering commentators. We hear the mother in Indiana whose GI son talked about his role at My Lai: ”I gave them [the army] a good boy, and they made him a murderer.” The film also uses interviews with witnesses such as the army officer who exposed his superiors’ complicity in the Abu Ghraib abuses, and the woman who found shared images of them on her soldier daughter’s laptop.

Hersh is given the last word: “We are a culture of enormous violence, just so brutal. You can’t have a country that does that and looks the other way.” Anybody interested in the history of modern America needs to check out this documentary, though a strong stomach may be needed.

Cover-Up is available in selected cinemas and on Netflix from December 26

Add comment