Volker Schlöndorff’s brilliant adaptation of Günter Grass’s 1959 novel The Tin Drum hasn’t aged one bit: just as the book and film’s main character Oskar Matzerath decides that it’s better not to grow old, the film’s phenomenal zest feels as fresh today as when it was won the Palme d’Or in Cannes and Best Foreign Film Oscar in 1979.

Set in Danzig (now Gdansk), Günter Grass’s home town, a crossroads between East and West, both German and Polish, the story takes place in the years leading up to the city’s take-over by the Nazis in 1933, World War 2 and its immediate aftermath. Oskar is a remarkable fictional creation, a reflection of Grass’s own childhood experience as well as a fairy-tale narrator and observer. He decides that his body should remain that of a child, but his mind follows a normal yet singular journey towards maturity. The toy drum is a talisman and powerful tool for Oskar’s self-expression.

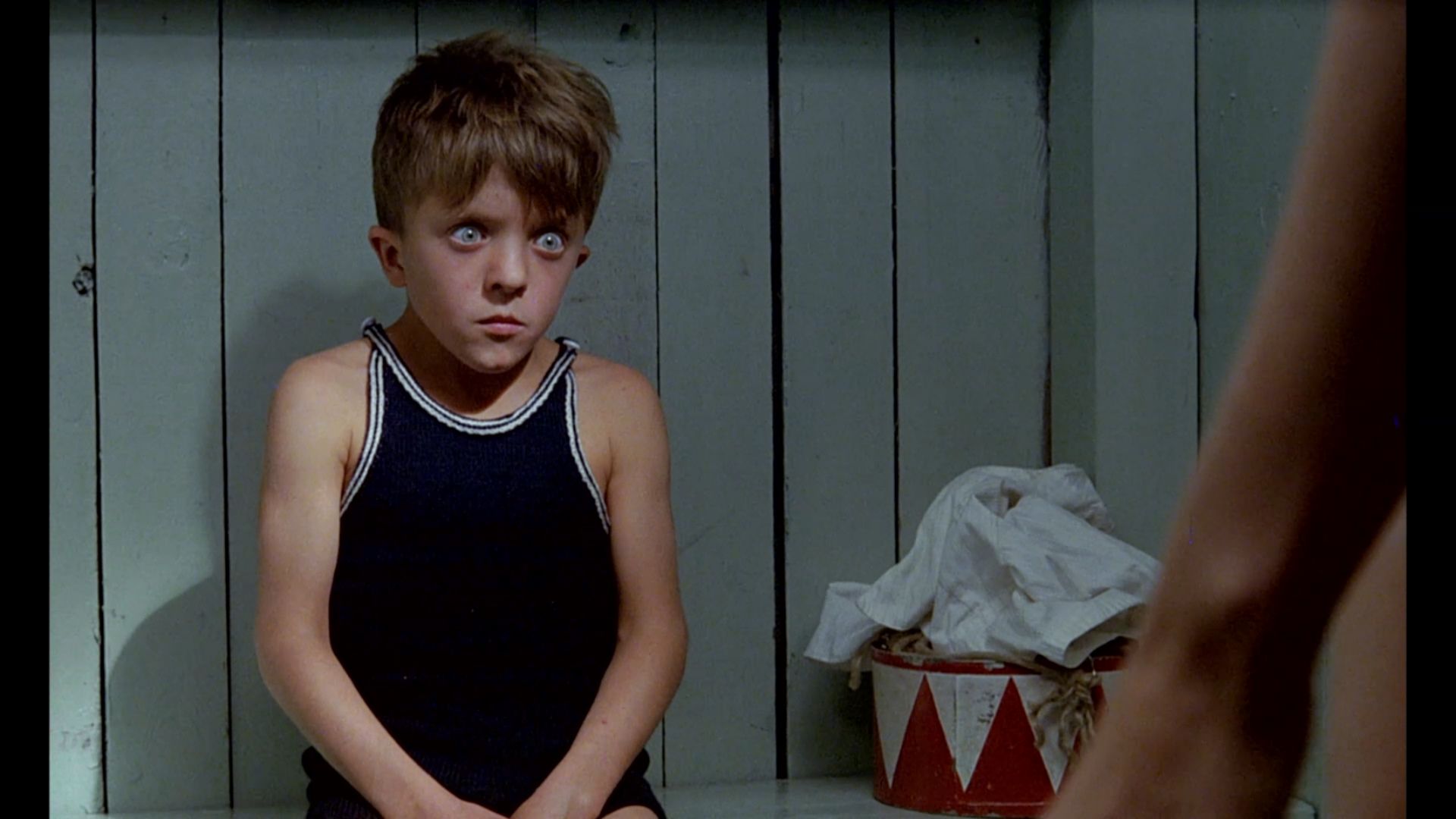

Oskar gazes with forensic amazement at his family and city, in wonder at the perversities of human behaviour, not least the almost animal lust that drives all those around him. He is tortured by other children, but frees himself from the hold of those who would control him by discovering that he can shatter glass by emitting high-pitched screams. There are so many poetic resonances with the essence of German Nazism, his screams and drumming echoes of the Führer’s rants and paramilitary marching bands. As Schlöndorff points out in an illuminating one-hour interview that forms part of this Criterion release, Oskar isn’t anti-Nazi or a victim either, but lusts for power and control over others. David Bennent (pictured below), who incarnates him on-screen, captures the complex mix of wide-eyed innocence and demonic scheming that make the diminutive hero both beguiling and disturbing.

Günter Grass lost a great deal of credibility (and for many his reputation) when it was discovered that he’d joined the Waffen-SS as a 17 year-old, and had never admitted this publicly. He wrote The Tin Drum, and created little Oskar, with that memory in mind. The book addressed the way in which ordinary people bought into the Nazi promise of earthly paradise. The warped lure of the uniform and the almost relgious thrill of the rallies are well evoked in the book and the film. With hindsight, could The Tin Drum’s fairy tale feel have something to do with a desire to consign historical fact into a mythic dimension? If so, the work is, paradoxically, all the more fascinating.

Oskar, with an innocence that calls to mind Grass’s joining the Waffen-SS as a teenager, becomes a collaborator when he joins a group of dwarves who entertain the troops at the front, wearing a miniature Wehrmacht uniform. The reality of Nazism is revealed in its full horror when, on his return to the front, Oskar is selected for euthanasia – even though the war is lost and the Russians at the gates of Danzig. His father refuses to hand him over to the Gestapo. He knows now – too late – that the euphemisms about re-location are a cover for murder in the name of racial purity. The father agrees with the principle of mercy killing the less than perfect, but his paternal love wins the day. This is one of many sequences in which the humanity of the characters shines through. It’s perhaps in the knowledge of his own compromised past and universal human frailty, that Grass was able to write such a stirring and richly layered novel. Schlondörff follows through with a film that expresses compassion as much as it describes the horrors of Germany’s past.

The film is enhanced by Maurice Jarre’s haunting soundtrack, never coaxing us too hard into a clichéed emotional response, but underlining shifts in mood with recurrent stabs of a low-pitched Jew’s harp and swathes of well-calibrated strings. One stunningly devised set-piece follows another seamlessly, from the terror of Kristallnacht and the burning of the central synagogue to the siege of the Polish post office on 1 September 1939, one of the first victories celebrated by Nazi propaganda, the moment when Oskar discovers an affinity with performing dwarves a the circus to the scene on the Baltic beach, where he watches a fisherman catch slithering eels with a dead horse’s head. The film weaves together, as the book did, an almost surreal mix of eroticism and horror, violence and kindness. None of this, deftly done as it is, suffers from being dated: the film mirrors humanity in all its splendour and frailty, exploring themes that reach far beyond the place and time of its drama.

When Jean-Claude Carrière (already famous for the scripts he wrote with Buñuel) and Schlondörff presented their first draft to Grass, he told them it was “much too Cartesian”, and needed to be crazier. They went for it, and the resulting film – with contributions to the dialogue by Grass - is funny, gripping, surprising, shocking, erotic, horrifying and bursting with poetry. It is immensely enjoyable to watch, as well as very moving. David Bennent’s central performance, with his wide-eyed stare is only one of many very well-cast performances. The cinematography (the Slovak DoP Igor Luther), editing and pacing never call attention to themselves but serve every aspect of the story perfectly well: this is a mark of the mastery of a director who remains surprisingly underrated. His bonus interview is nothing less than a masterclass in intelligent, sensitive and creative film making.

Add comment