Stylistically, Waxworks (1924) was the apogee of German Expressionist cinema in that it was the last pure distillation of the form, in which visual distortion, chiaroscuro, exaggerated staccato acting, and nightmarish atmosphere collectively evoked the angst-ridden German collective consciousness in the early years of the Weimar Republic.

Waxworks proved influential, too, especially as an anthology film with horror elements. Yet it has never been as celebrated as such Expressionist classics as The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919), The Golem (1920), Nosferatu (1922), Dr Mabuse the Gambler (1922) or Metropolis (1926). That may be because the first of Waxworks' three sections, at 40 minutes the longest, doesn’t partake of the anticipated Gothic dread but is a piece of comic exoticism in the vein of Ernst Lubitsch’s Sumurun (1920), of which it was presumably a parody. Indeed, in his audio commentary, the Australian critic Adrian Martin asserts that Waxworks is a self-conscious satire in its entirety, one in constant dialogue with The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, as suggested by its German title, Das Wachsfigurenkabinett.

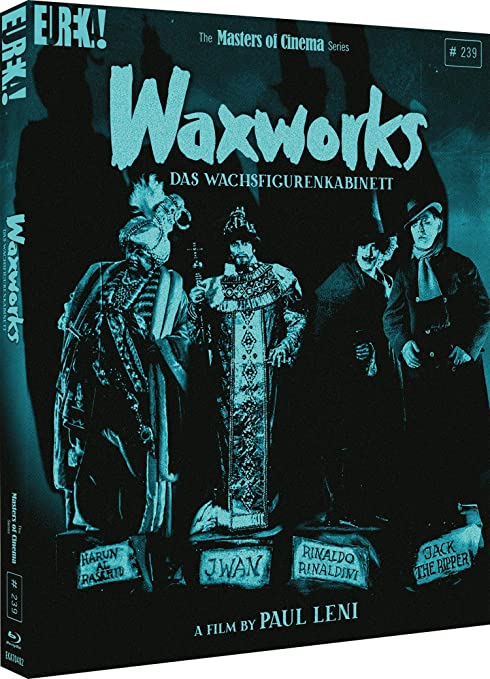

At a fairground, a nameless young man (Wilhelm Dieterle, who would change his name later, while working in Hollywood, to William) is hired by a waxworks proprietor (John Gottowt) to write stories promoting his figures. They include Haroun al-Raschid (played by Emil Jannings), the real life 8th century Caliph of Baghdad, who was fictionalised in The Thousand and One Nights; Ivan the Terrible (Conrad Veidt); and Jack the Ripper and his doppelgänger Spring-heeled Jack (Werner Krauss, unrecognisable from his portrayal of Dr Caligari, played both).

At a fairground, a nameless young man (Wilhelm Dieterle, who would change his name later, while working in Hollywood, to William) is hired by a waxworks proprietor (John Gottowt) to write stories promoting his figures. They include Haroun al-Raschid (played by Emil Jannings), the real life 8th century Caliph of Baghdad, who was fictionalised in The Thousand and One Nights; Ivan the Terrible (Conrad Veidt); and Jack the Ripper and his doppelgänger Spring-heeled Jack (Werner Krauss, unrecognisable from his portrayal of Dr Caligari, played both).

A fourth waxwork, the fictional noble banditti captain Rinaldo Rinaldini, also appears. But the segment concerning him, to have starred Dieterle, was dropped by Leni, possibly for budgetary reasons. As it is, Dieterle’s storyteller casts himself alongside his boss’s daughter Eva (Olga Belajeff), who’s smitten with him, in each of his three tales.

The best and scariest is the middle one: Veidt is astonishing as the paranoid first Tsar (crowned in 1547) who goes mad when he gets a taste of the extreme psychological torture he inflicted on others. The first story, about a poor Baghdad baker who tries to steal the Caliph’s wishing ring to appease his unhappy wife, is only mildly amusing but certainly artier – if less robustly spectacular – than Raoul Walsh’s Douglas Fairbanks vehicle The Thief of Bagdad, also made in 1924.

The third story, in which the two Jacks menace the storyteller and Eva in a dream, is a meta-vignette that, in its murkiness, augurs Alfred Hitchcock’s Jack the Ripper suspect thriller The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927); there’s also something of Krauss’s elegant Ripper in the Mackie Messer of GW Pabst’s The Threepenny Opera (1931).

Waxworks was Leni's last German film. Signed by Universal in America, he directed The Cat and the Canary (1927), The Man Who Laughs (1928) – the latter starring Veidt – and two other films before dying from sepsis at the age of 44. A visionary production designer who was shaping up to be a master director, he was sophisticated in his recognition that stylised sets and costumes were conduits to the psyche: “It is not extreme reality that the camera perceives, but the reality of the inner event, which is more profound, effective, and moving than what we see through everyday ideas.” As rivals and collaborators at Universal, Leni and James Whale might have made horror Hollywood's most transcendent genre.

Martin’s insightful commentary draws attention to Leni’s use of doubles and vertical space, as well as his prediction, evinced through dissolves and other techniques, that in films of the future the medium would be the message. While praising the scholarship of Weimar cinema and German Expressionist film’s foremost historians Siegfried Kracauer, Lotte Eisner and Thomas Elsaesser, Martin queries some of their assertions, notably Kracauer’s insistence that Waxworks and other “imaginary tyrant films,” including Nosferatu and Dr Mabuse, were harbingers of Hitler and Nazism. This is a point forever moot.

The other supplements on this Masters of Cinema release are an invaluable interview with Deutsche Kinemathek's Julia Wallmüller, who explains why the digitally restored Waxworks (based on a BFI print) is 25 minutes shorter than Leni’s original; a lively talk by British critic Kim Newman on wax museum horror films; and Leni’s 1925 short Rebus Film Nr 1, which playfully harnessed archival footage and animation to set up a crossword puzzle’s clues and answers and was shown in two parts before and after feature presentations.

Add comment