Moon Is the Oldest TV review - a fitting tribute to a visionary modern artist | reviews, news & interviews

Moon Is the Oldest TV review - a fitting tribute to a visionary modern artist

Moon Is the Oldest TV review - a fitting tribute to a visionary modern artist

Authoritative documentary that defines the genius of Nam June Paik

Who created the term “electronic superhighway”? First described a system of linked communication that would become the internet? Envisioned a multichannel TV system where viewers chose for themselves what to tune into? Watch Amanda Kim’s excellent documentary Moon Is the Oldest TV and you find that the correct answer to all those questions is Nam June Paik.

A diminutive impish South Korean, Paik was born into an eminent wealthy Seoul family, on a par with the Samsungs, and by 17 knew he had to get out. He had become a Marxist, then a communist. His intellectual interests would take him to Europe, the US and a whole new world, far from the chauvinist militarism of South Korea.

Paik’s biography delivers surprises at every turn, much as he did. He didn’t begin as an artist. He was a skilled musician who received a PhD in renaissance music, then topped that off with a second PhD, in philosophy, majoring in Hegel. He ended up speaking 20 languages, all of them badly, he would admit with a broad grin.

This is the keynote of Kim’s film: the great and the good of modern art contribute – curators, artists, critics, students – and all are smiling as they remember Paik.

But what did he do? Solo exhibitions of his work weren’t staged that often in the UK until Tate Modern did him proud with a huge show just before the pandemic closed its doors. He is hailed by many in the film as the world’s foremost practitioner of video art, which he took up decades before others realised the potential of this new piece of kit. And even that’s too reductive to describe his achievements properly.

Paik came to art via music studies in Munich, drawn there in 1956 by his passion for the pioneering composer Arnold Schoenberg. He came to hate the domination of “Western” music, which he represented by smashing pianos and taking a violin for walks on a lead. When he came across John Cage in 1958, who scraped the strings of his prepared pianos and left audiences wincing, Paik knew he had found his lodestar. After that he would refer to time as BC (Before Cage).

He found new allies in Wiesbaden’s Fluxus group, who included Yoko Ono, and in the artist Joseph Beuys and film-maker Jonas Mekas, who encouraged the performance artist in him. And he found a new language to learn, television: he bought one, opened up the back and rebuilt it for his own purposes. By the simple act of standing in the hole where the screen had been, eating an apple, he suggested people should think hard about this new technology: did they want to be passive consumers of it or the ones moving the dials? His 1963 Wuppertal show was the first to feature a TV set. "I use technology in order to hate it properly," he said.

Sets of every size, programmed by Paik to screen his video work, would become the defining staple of his art, as felt and wax were to Beuys. When he Inevitably moved to the-then great centre of modern comms, New York City, he shared a flat with 16 sets and two robots. He would go on to create glasses made from little TVs, a TV bra for his regular collaborator the cellist Charlotte Moorman (who appeared once with propellers on her nipples), a TV Clock, a TV Mother and Father, a giant TV skyscraper, a 1974 map of the United States, with a live TV in each state, called Electronic Superhighway. And, as per the film’s title, a TV with a “moon” on its screen that waxes and wanes, programmed by Paik himself.

He also made two scrappy robots in 1964 that express all his scorn for modern technology’s ambitions for supremacy: they had genitals and anuses, they walked with a stagger and spouted JFK’s “Ask not what you can do for your country" speech on a loop. And around that time the great leap forward of video tape recorders arrived, whereby, Paik realised, anybody could become an information provider (a phase we are still going through).

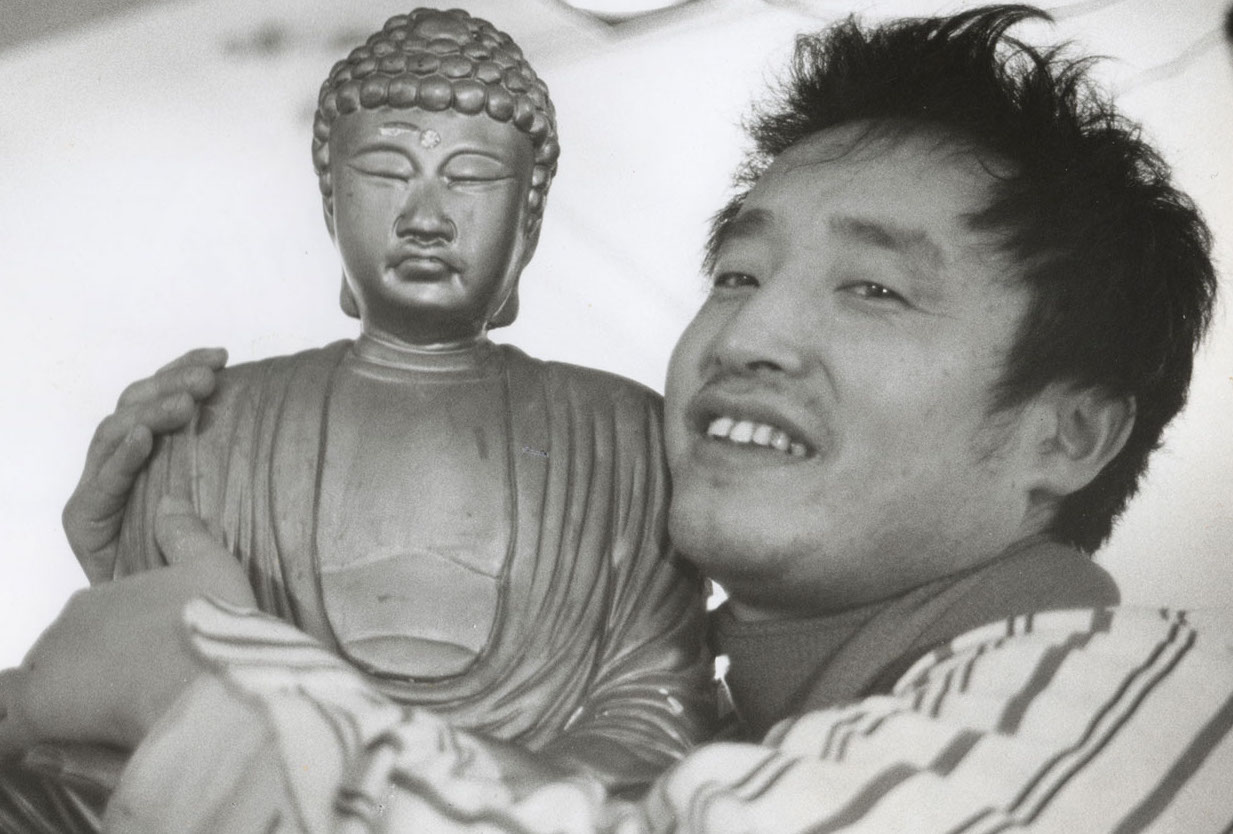

But in the 1960s, video art was ranked the lowest of the art forms, lower even than photography. Even though Paik was arguing for the primacy of human beings over technology, the critics were bewildered and unsympathetic. He realised he would always be an outsider everywhere, not just in Seoul. And his art was expensive to create.  He had only just begun, however. With a Rockefeller Foundation grant, he went on to create work at a TV station, designing a synthesiser for reproducing television images cheaply – the Japanese manufacturers to which he sent his spec design were amazed as the programming skills he required hadn’t been developed yet. His Global Groove shows were live-streamed by WNET in Boston. And finally he found a money-maker, an image of Buddha watching himself on television. He even masterminded a TV spectacular, which went out by satellite around the world on January 1 1984, called Good Morning, Mr Orwell. It featured names such as Bowie, Laurie Anderson, Merce Cunningham, a stoned Allen Ginsberg and John Cage, a drunken George Plimpton. It was a car-crash, but a classic Paik moment: “I just let it happen.”

He had only just begun, however. With a Rockefeller Foundation grant, he went on to create work at a TV station, designing a synthesiser for reproducing television images cheaply – the Japanese manufacturers to which he sent his spec design were amazed as the programming skills he required hadn’t been developed yet. His Global Groove shows were live-streamed by WNET in Boston. And finally he found a money-maker, an image of Buddha watching himself on television. He even masterminded a TV spectacular, which went out by satellite around the world on January 1 1984, called Good Morning, Mr Orwell. It featured names such as Bowie, Laurie Anderson, Merce Cunningham, a stoned Allen Ginsberg and John Cage, a drunken George Plimpton. It was a car-crash, but a classic Paik moment: “I just let it happen.”

HIs life was by no means all puckish glee. Living hand to mouth for most of his adult life took its toll on his health, though even after a stroke in 1996 he continued with his art until his death in 2006. “Brain is working.” As one commentator notes, he paid the price for being so ahead of his time. It’s a shame he isn’t still here to make work that addresses AI directly.

Kim pays tribute to his art with her own, presenting imagery as if it was created by some Paik programming, swirling and mutating, speedily cross-cut and enhanced with beautiful electronic music (much of it by Ryuchi Sakamoto). This stunning film makes Paik both understandable and an art-world luminary who really deserved the title “genius”.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment