If you tell a tall, whisper-slim young woman of 31 that she has been described as "the soul of Russia", it is understandable that she looks startled. Two huge, smoke-grey eyes cast a doubtful glance at me, and she murmurs in Russian. Her translator announces: "That is a very serious declaration."

So it is. And yet Uliana Lopatkina, despite her tender age, is now lionised almost universally as the greatest ballerina today in Russia, a country where they know about such things. Effortlessly, it seems, in the 10 years since a 5ft 9in beanpole with a square jaw and an apparently boneless body emerged from the juniors of the Kirov Ballet, a living legend has grown up around her. Even with its bursting crop of world-class ballerinas, more beautiful, more glamorous, more modern, than Lopatkina, Russia's ballet world falls back quite naturally to look up to her as prima. When the Kirov visits London this summer, Lopatkina will open and close the season, in the landmarks of classical ballet Swan Lake and La Bayadère.

Porcelain-pale with her open gaze and chestnut bob, wearing something classic and brown with a scarlet scarf, she cuts a gentle, even studenty figure. She has too unassuming a presence to be a ballet icon - not to mention man-sized feet. Russian ballet had been known for its small, delicate women, but the then Kirov director Oleg Vinogradov was mad about Sylvie Guillem and eagerly started unearthing tall new girls in her image - his "basketball team", as they were known.

In public gatherings of Kirov dancers, young Lopatkina appeared sober, gawky, even plain, compared with the brazen Anastasia Volochkova, or the doll-beautiful Diana Vishneva, let alone the company's gorgeous superstar, Altynai Asylmuratova, who could look a real disco kitten when she wanted to.

In public gatherings of Kirov dancers, young Lopatkina appeared sober, gawky, even plain, compared with the brazen Anastasia Volochkova, or the doll-beautiful Diana Vishneva, let alone the company's gorgeous superstar, Altynai Asylmuratova, who could look a real disco kitten when she wanted to.

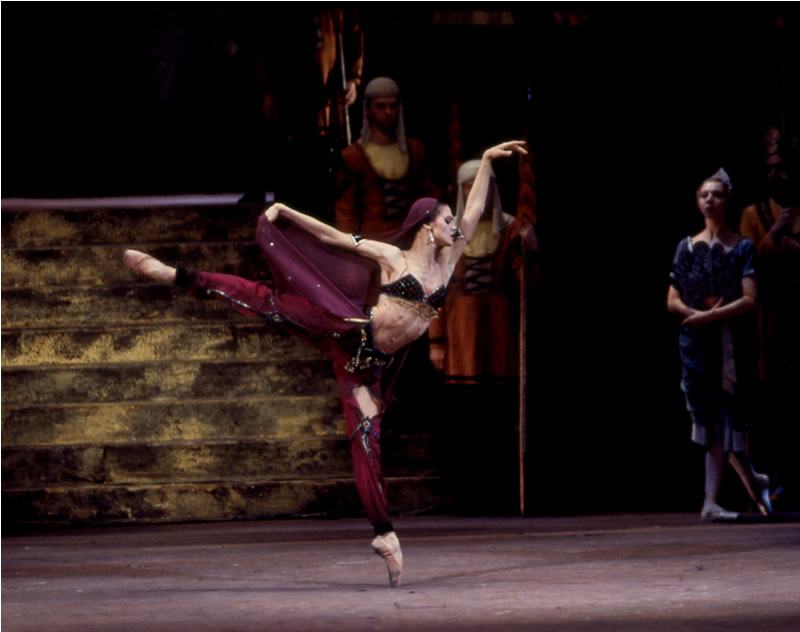

But in 1995 young Lopatkina was the Kirov's cover-girl on their London visit, writhing in pantaloons, playing serpentine sex-bombs suffering in harem ballets, yet banishing all vulgarity with the dark nobility in her eyes (pictured left as Nikiya, courtesy Mariinka). And then, when she unfolded her endless limbs in Swan Lake, one felt a frisson of fear at her unfathomably upsetting exposition of the threat of good and evil to man's soul.

Even though the translation of her explanation sounds too simple for her voluble Russian answer, it hints at Lopatkina's depths. Fairy-stories such as Swan Lake or Sheherazade, she says, are written for children "to learn about life from them. They learn what is good, what is bad, they learn about love's ways, and about loyalty. These ballets bring forward these issues in an adult way.

"I usually don't try to judge the females I portray, just to explain them, as in life, too, we sometimes have to try to explain situations and people from our experience rather than judge them. This way the public can decide whether to judge the person I play negatively or not."

Being a ballerina, she says, is integral to her life. It defines her. But she could do without the high-priestess image. She sighs. "Some people do like having legends. It's all out of my control, this legend image - and it does put a lot more pressure on me, because I really can't make any mistakes now! The positive side is that because of people's expectations of this spiritual fulfilment and elegance in my dancing, I really do my best, it drives me even if I can't always live up to their expectations."

It is easy to warm to Lopatkina, especially when she jumps up to demonstrate to me the difference between oriental "plastique" and the upright poise of classical ballet. As she suddenly turns into a hip-rippling houri, she claims to have given the erotic effect not a thought: "For me what was important was the plastique, the broad movements of the limbs." Then, drawing herself up into the taut poise of the grand ballerina, she says: "The French [classic] style of ballet can be no less sexual, but in a different way," and she bats her eyelids and simpers amusingly.

One of the most curious things about Lopatkina is her apparent absence of curiosity. Her repertory has hardly changed at all in 10 years. Almost every ballerina alive would give her eye teeth for new leading roles, the work of today's leading choreographers, and for Kenneth MacMillan's gloriously wicked Manon, now a Kirov favourite.

But Lopatkina is a law to herself. "I was given the choice by the management to take Manon or not, and I looked at the character and the book and decided that it was alien to me." I protest that no one can plead better than she on behalf of fallible females. "Well, I agree that the story has a lot of food for thought, but I just didn't feel any light in my soul. It's just my personal reaction. I don't think I'll change my mind."

To William Forsythe's razor-edged modern ballet, she also says no - "there is no heart" and it is "too radical on the body". She danced it in Russia, made her decision, and the Kirov's Forsythe programme in London will go on without her.

She also censors her classical roles because of her firm ideas of what a ballerina role should look like. She believes she can suit a "big" princess, like Raymonda, but not a "petite" one, as she has always imagined Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty - she prefers the secondary role of the Lilac Fairy. And although she performs some of George Balanchine's more romantic roles (La Valse in London), she believes, to my great chagrin, that she is too heavy for men to partner in his neo-classical masterpieces, Apollo and Agon.

She appears to have an astonishing power of choice in the Kirov, and yet she exercises that choice astonishingly narrowly. "I know it's often suggested that artists must be diverse and show all facets of their talent, but to me better than diversity is to think what is closest to your heart, what you really can do. I am lucky that I have this choice."

Very rarely ballet throws up an artist who embodies more than supreme skill and theatrical personality, and comes to epitomise a sort of national dream

When did she get that choice? She doesn't know. It happened. But inside the Russian ballet establishment, there seems to be some consensus that she is too special to be buffeted about by normal orders.

She is revered by the Maryinsky Theatre's supremo Valery Gergiev, and theatre staff speak highly of her. Very, very rarely ballet throws up an artist who embodies more than supreme skill and compelling theatrical personality, and comes to epitomise a sort of national dream. Galina Ulanova and Margot Fonteyn suffered that fate, and it looks as if Lopatkina is being pushed the same way.

It does all feed a worry - at 31 she is much too young to ossify in a tiny repertory, walled up in a myth. She might just get grand and mannered. Or she might even stop altogether.

During a long foot injury, Lopatkina got married and had a daughter, Maria, now three (pictured right, mother and child, courtesy Mariinsky). Since her return, she has danced quite rarely. "I have become more choosy now, what I dance, how I dance.

During a long foot injury, Lopatkina got married and had a daughter, Maria, now three (pictured right, mother and child, courtesy Mariinsky). Since her return, she has danced quite rarely. "I have become more choosy now, what I dance, how I dance.

I am terrified what resonance it will have for the future of my child. I imagine myself at my death, thinking, did my child see me do the best thing for her, did I live my life right? Those sort of thoughts are always with me now."

It's tempting to put this down as a temporary bout of new-mother over-sensitivity, but with Lopatkina one can't be sure that what seems a normal bit of scarring will occur. What makes her dancing so unforgettable is that it shows the soul's wounds so clearly.

Is she thinking she must choose between being ballerina or mother? She pauses an alarmingly long time, and murmurs again. "Even if I have the opportunity to have another child, I will not be able to detach myself from my life in art. This is how I feel today." We can breathe again, at least for today.

Add comment