In 2007, Pina Bausch was preparing her company’s latest “city piece”, this one based on a visit to Kolkotta. But she was also brewing up something special, a work for six of her long-serving women dancers, created separately from the city piece but out of the same set of questions.

Even if Bausch hadn’t somehow sensed the need to do something for her female troupers while she could (she died suddenly in 2009), the piece is inherently like a memorial, a call for the dancers to be remembered. Indeed, they insist on it. These are regular self-exposers, anyway – a line of beauty queen contestants in 1980, the first Bausch piece staged at Sadler’s Wells by the Wuppertalers, in 1983; bodies for sale in Kontakthof, displaying their teeth and hands – and always living components of every piece, sometimes half-naked, whose personal experiences are woven into its fabric.

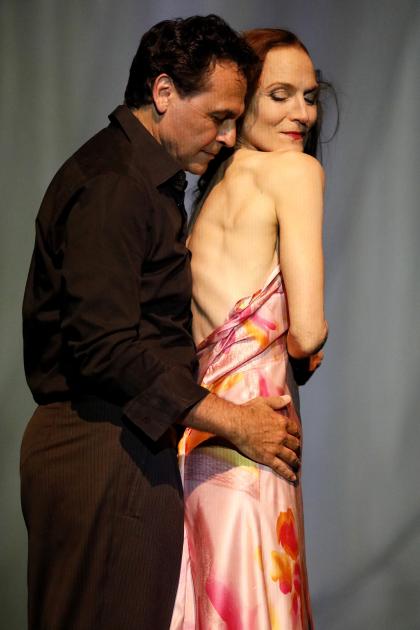

In Sweet Mambo they directly call out for recognition, spelling out their names, demanding not to be forgotten. Daphnis Kokkinos (pictured right, with Stanzak) is obsessed with getting his height correctly noted: “180cm!! Don’t forget”. Julie Ann Stanzak works her way around her body, identifying which family members donated the genes for them. Naomi Brito dares the audience to get the pronunciation of her name wrong.

Brito, a mischievous, high-kicking performer, is one of three dancers in the lineup who didn’t originate the role two decades ago. The rest, unbelievably, are the same people who went through the rehearsal process back in 2007-8, devising answers to Bausch’s questions in her signature way. Some began their Wuppertal careers 40 years ago. All are in their fifties and sixties; one, the indomitable Nazareth Panadero, is 70. So there is a built-in elegiac quality to their appearing in the piece.

It is not solemn at all, though. Backed by smoochy Latin rhythms and trip-hoppy interludes, it’s strong on yearning and dreaming, reflected in Peter Pabst’s most lyrical set (shared with the Kolkotta piece, Bamboo Blues). Floor-to-flies white voile curtains drift and billow, with extra ones that rise and descend and a side curtain that’s pumped up by an invisible fan into a giant beluga whale shape. As the piece moves on, scenes from the 1938 comedy The Blue Fox are projected onto the backdrop.

The women are, as ever, in the late Marion Cito’s clever silky frocks, the skirts bias-cut for guaranteed beautiful swirling. They change into short cocktail dresses and slips in places, but their look is the usual one, all long swooshing hair and elegant fabrics, with spaghetti-strap bodices that they are always threatening to fall out of. And the men – three of them, whom Bausch realised she would have to include as necessary muscle for some of the sequences the women had devised – are in standard black shirts and trousers, with one glorious costume change for Kokkinos, who appears in a black see-through shift, and dress shoes that are four sizes too big, he complains.

It’s familiar Bausch territory thematically, too, a world of small triumphs and big disappointments, often involving the opposite sex. Aida Vainieri does a funny imitation of the man in LA who kept pestering her to talk to him, to her annoyance, then uses the pest’s lines on a young man (Alexander López Guerra) she really wants to talk to, who doesn’t want to talk to her. Eventually she realises she might be okay just talking to herself, the cue for a poignant slow solo to Hope Sandoval’s “I don’t think I’ll come around any more”.

There’s sadness, too, in Helena Pikon’s appearances in a full-skirted brown dress (pictured left), as if in mourning and singing (in a beautiful clear voice) a song about a little bird that only stops flying when it dies. But she also projects an unbridled skittishness, bouncing up and down on López Guerra’s lap in a sparkly mini-dress while calling out to people she is watching through red plastic opera glasses, and offering to scream for a man in the audience with a problem. She’s as enigmatic and arresting as ever.

Panadero, intermittently in mad blonde wig and glasses, sums up the mood when she first appears, flexing latex gloves, and intoning, “It’s nasty, isn’t it?”. Life, she goes on to declare, is like riding a bike: you either ride or fall off (maniacal laugh). She inspires great amusement, but also awe, especially in a duet with López Guerra, the youngest member of the cast, her fine arched feet still strikingly nimble.

The three men are less aggressively deployed than usual. They partner and primp the women, move furniture, actually become furniture in one lovely scene where they create “seats” behind the curtains for the women to sit on, as if floating. Andrey Berezin rolls on the floor like a stranded beetle, idolising Stanzak, but he will also nudge and annoy her, and pull her hair. All get a solo, along with the women, Berezin’s slow and thoughtful, López Guerra’s full of wild, expansive movements to Portishead, and Kokkinos’s showing he still has full technical mastery, with graceful port de bras, along with an ability to worm along the ground like a soldier on an assault course.

Stanzak, due to retire this year, is like a gracious host for the proceedings, instructing us in how to tackle a nerve-wracking party: just keep saying “brush”, she urges, which will make your mouth smile just the right amount. The other Julie (Shanahan, pictured above right, and bottom), is predictably the one who most directly channels her nightmares, notably in a sequence where she tries to cross the stage to a voice calling her name, only to be held back by two of the men; as her attempts grow more determined, her hysteria rises until she is screaming into the void.

Shanahan ends the first half, prostrate and soaking wet after pleasuring herself with buckets of water. She ends the piece, too, with a lengthy solo full of yearning arms and sweeping gestures, regularly caressing herself. She is perhaps the quintessential Bausch woman, strong, graceful and resilient but not without high anxiety about her world. She and the other women here, making no concessions to their physical ages, are a one-finger salute to all the misogynists and ageists in today’s world. It’s an unmissable event, and not just for Pina Bausch fans.

- Sweet Mambo at Sadler’s Wells until February 21

- More dance reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment