America in Pictures: The Story of Life Magazine, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

America in Pictures: The Story of Life Magazine, BBC Four

America in Pictures: The Story of Life Magazine, BBC Four

How the camera captured America's golden age

Before the internet and the Kindle were invented, generations of Americans saw their lives refracted through the pages of Life magazine. In particular, through its photography, since writers at Life were largely relegated to supplying glorified picture captions. They were also allowed to carry the photographers' equipment.

Obviously the idea of being an object of reverence appeals to photographers. Portrait and fashion snapper Rankin has long admired the work of the great Life lenspersons, and in this film he reviewed their accomplishments and tracked down some of the magazine's fabled survivors. Not that Rankin is the world's greatest TV presenter, frankly. His voice is the sort of nondescript Home Counties drone that American satirists love to parody. As an inquisitor, he looked a bit blank when he found himself face to face with the likes of Burk Uzzle, now retired to small-town North Carolina after a vivid career in which one of many highlights was being assigned to document Hugh Hefner and his voluptuous Playmates at Hef's mansion.

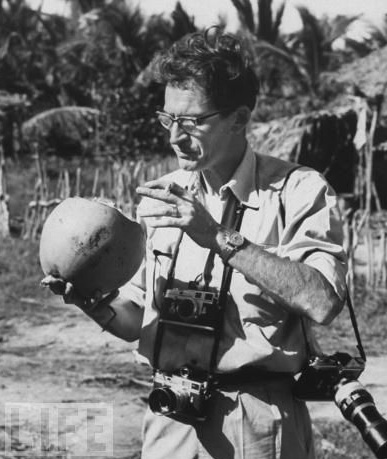

Luckily, though, most of his subjects were rather awesome characters who had no difficulty in filling the screen unaided (Life photographer Bill Eppridge, pictured right). Indeed, this seemed to be rather the point - a photographer isn't, or shouldn't be, just some geek who knows how to work a camera and programme an array of electronic flashguns. He or she needs to bring empathy, insight, patience and frequently courage to an assignment if they're going to bring back anything that will resonate with readers.

Luckily, though, most of his subjects were rather awesome characters who had no difficulty in filling the screen unaided (Life photographer Bill Eppridge, pictured right). Indeed, this seemed to be rather the point - a photographer isn't, or shouldn't be, just some geek who knows how to work a camera and programme an array of electronic flashguns. He or she needs to bring empathy, insight, patience and frequently courage to an assignment if they're going to bring back anything that will resonate with readers.

Amid a mostly male roll call, Margaret Bourke-White inevitably stood out, not only because she was a fabulous photographer, but also for the way she candidly used her sexuality to gain maximum professional advantage. A highly successful tactic was bedding American generals in order to get priceless wartime scoops. A rival lensman was chastised by Life HQ because she was beating him to the best stories. He cabled back: "Bourke-White has a piece of equipment that I don't have."

But there were many other stars in the dazzling Life firmament. Alfred Eisenstaedt (pictured left with Marilyn Monroe) was the magazine's grand eminence, and a pioneer of the "candid" style in which he used a Rolleiflex camera held unobtrusively at waist level. W Eugene Smith did pioneering work in the photo-essay genre, gaining extraordinarily intimate access to his subjects in stories like "Career Girl" or "Country Doctor". Rankin noted that "Smith was a tortured genius, Life's Van Gogh." John Loengard shot Marilyn Monroe, The Beatles and the Vietnam War.

But there were many other stars in the dazzling Life firmament. Alfred Eisenstaedt (pictured left with Marilyn Monroe) was the magazine's grand eminence, and a pioneer of the "candid" style in which he used a Rolleiflex camera held unobtrusively at waist level. W Eugene Smith did pioneering work in the photo-essay genre, gaining extraordinarily intimate access to his subjects in stories like "Career Girl" or "Country Doctor". Rankin noted that "Smith was a tortured genius, Life's Van Gogh." John Loengard shot Marilyn Monroe, The Beatles and the Vietnam War.

Life became so singular and influential during the mid-20th century, when 100 million readers would see it every week, that the question inevitably arose of to what extent the magazine was making the news rather than merely recording it. John Shearer's assignments covering the Civil Rights protests in the 1960s became a part of the fabric of social change, as did his astonishing work during the 1971 Attica prison riot. Shearer spent four days inside the jail as a ferocious miniature war raged, leaving 41 men dead.

Life took a dim view of the Vietnam conflict and ignored demands to tone down its frequently shattering battlefield photographs. British photographer Larry Burrows (seen in clips from a 1969 Omnibus film) talked about his concerns that he was exploiting wartime deaths and suffering, but felt his pictures were justified if they "contribute to the understanding of what others were going through". He was killed in Laos in 1971 (Larry Burrows, pictured right).

Life took a dim view of the Vietnam conflict and ignored demands to tone down its frequently shattering battlefield photographs. British photographer Larry Burrows (seen in clips from a 1969 Omnibus film) talked about his concerns that he was exploiting wartime deaths and suffering, but felt his pictures were justified if they "contribute to the understanding of what others were going through". He was killed in Laos in 1971 (Larry Burrows, pictured right).

Rankin reckoned that it was the arrival of celebrity culture in the 1970s which pulled the carpet out from underneath Life, which published its last issue in December 1972. Celebs were going to rule, and the intimate, deeply researched work that Life had specialised in would become outmoded. Glaswegian snapper Harry Benson, a transplanted Daily Express veteran, was in at the death of Life, and famously became the man who gained access to mad chess genius Bobby Fischer as he played his epic tournament against Boris Spassky in Iceland. The recent documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World gave the impression that Benson had become friendly with Fischer, but the photographer didn't see it that way.

"Everyone knew he was a piece of shit, he was terrible!" he declared. "But it was worth fighting for, to get as close as you can and then get out." He never, ever wanted to become friends with any of his subjects, he added. Photography was apparently no mere popularity contest.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Comments

What could have been an

Im not a massive fan of

......i also thought this was