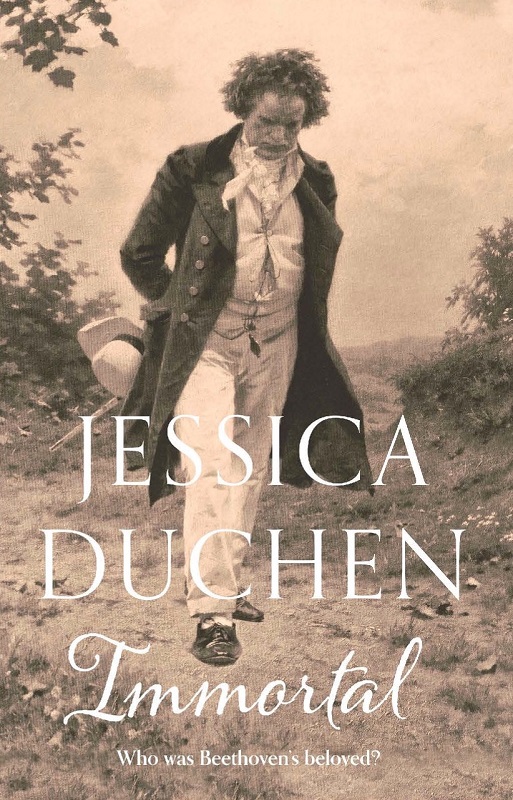

The identity of Beethoven’s “Immortal Beloved” is one of the biggest cans of worms in musical history. I hadn’t the slightest intention of writing a novel about it. At first I thought I’d create a narrated concert for the anniversary year... but that was then. Here we are and Immortal is now out.

It all began when I was asked to speak about “Beethoven and Women” in a string quartet festival a number of years ago. I started reading and couldn’t stop. The love story I found hidden amid the many thousands of pages was bigger, more complex and more devastating than I’d anticipated, beginning as early as 1799 and continuing for the better part of 20 years. It starts a step away from Jane Austen, yet by the end is pushing towards Tristan and Isolde. Moreover, Viennese academics and the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn are now 90 per cent sure that it’s true.

All the more reason to present a version that has all the prerequisites of duck resemblance in a readable and convincing way. Historical fiction is woven from many more unlikely topics; if the building of a cathedral, the scandals of the Tudor monarchy or the convolutions of the Dreyfus Case can make good novels, why not this?

All the more reason to present a version that has all the prerequisites of duck resemblance in a readable and convincing way. Historical fiction is woven from many more unlikely topics; if the building of a cathedral, the scandals of the Tudor monarchy or the convolutions of the Dreyfus Case can make good novels, why not this?

The woman in question: Countess Josephine Brunsvik von Korompa – later, Countess Josephine Deym; later still, Baroness von Stackelberg (yes, it’s complicated). The reason it matters: decades ago, a musical motif was identified as possibly associated with her in many of Beethoven’s works. It is in the Andante favori: “Jo-se-phin-e, Jo-se-phin-e...”. Soon it was glaring out at me from piece after piece. It all began with a song and piano duet variations, Ich denke dein, that he wrote for Josephine and her sister, Therese, in 1799 when they became his piano pupils.

By this point it would have taken a tougher writer than me to resist plunging in to this tale, but it did mean approaching Beethoven with fresh eyes and ears, not as the demigod we tend to create out of him, but as a human being. I spent a week tramping around Vienna, finding those of his footsteps that remain. The weather was chilly and gloomy and I had the mother of all colds. Nevertheless, the trip was invaluable. Beethoven was a foreigner here and even today it is not his music that blares out of every tourist shop and café, but Mozart, Haydn or Johann Strauss. Perhaps local perceptions of him – distorted into wildness, madness and ugliness for centuries after his death – were coloured by the fact that he was simply an outsider. He spent 30 years or so in Vienna, loathing it. Thinking of his native Bonn, with its broad riverscapes and straight-talking inhabitants, I’m no longer surprised.

As for relevance to today, this story has more than I originally anticipated when I started stumbling over references to the earlier plague outbreaks in Vienna and a typhus epidemic in 1817. Pandemics aside, though, Immortal is ultimately about how a society that oppresses one part of its population also harms its whole. When women are oppressed, it ruins men’s lives too. Yes, there are many novels already about Beethoven – but possibly not feminist ones.

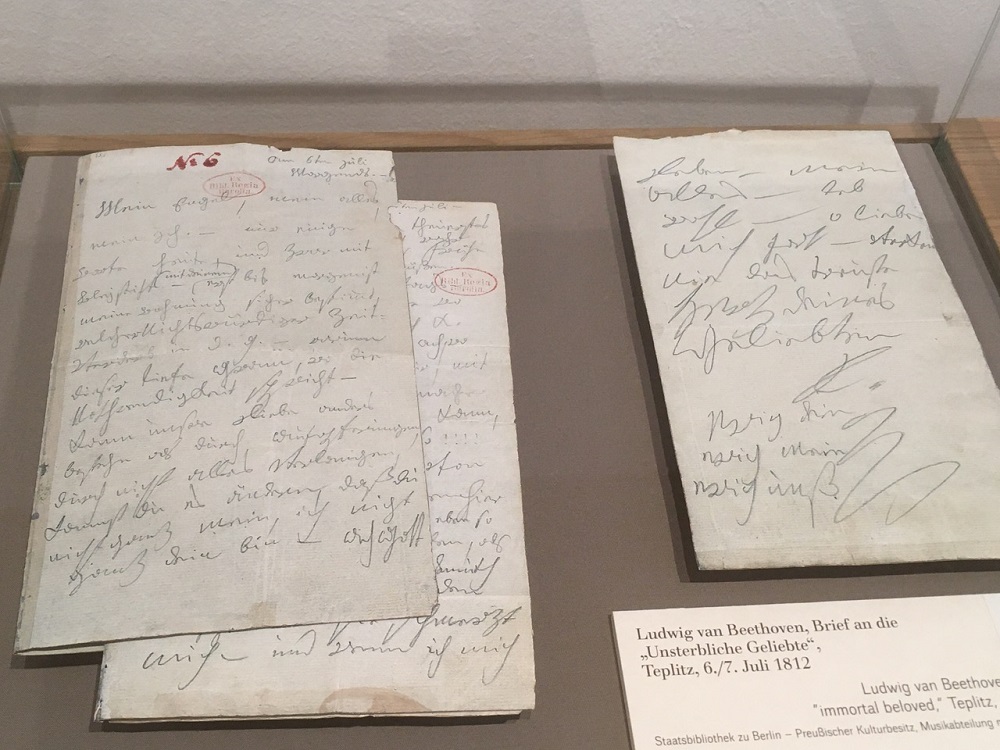

Josephine, nicknamed Pepi, was subjected to, among other things, the ferocious control of her aristocratic families, the lack of rights for widows, the terror of losing her children and the attentions of snake-in-grass men – compared to whom Beethoven emerges as a shining example of idealism, integrity and devotion. Pepi was no victim by nature. Effectively a modern woman in tune with her needs and desires, she was intelligent, cultured and a talented pianist, and enjoyed luxury and lively society; she made gigantic sacrifices for the sake of her children; and she fought back at every turn, as you would expect from Beethoven’s soulmate. Yet in the end her inevitable destruction contributed, if you trace the way through complex cause and effect, to the demise of the composer himself. Just think: if they had been free to marry, we might have had nine more symphonies. (Pictured below: Beethoven's letter to his "immortal beloved")  What about the 10 per cent of doubt? The only way to solve it – potentially – would be to dig up the composer and the person who may have been his illegitimate child for a DNA test, and I doubt anybody has the appetite for that. Up to a point, then, it will always be fiction. I’ve given the novel’s first-person narration to Josephine’s sister, Therese, a remarkable woman in her own right: a pioneer of feminism and founder of kindergarten education in Hungary, Bavaria and beyond, a close friend of Beethoven, and the dedicatee of the Piano Sonata in F sharp, Op. 78.

What about the 10 per cent of doubt? The only way to solve it – potentially – would be to dig up the composer and the person who may have been his illegitimate child for a DNA test, and I doubt anybody has the appetite for that. Up to a point, then, it will always be fiction. I’ve given the novel’s first-person narration to Josephine’s sister, Therese, a remarkable woman in her own right: a pioneer of feminism and founder of kindergarten education in Hungary, Bavaria and beyond, a close friend of Beethoven, and the dedicatee of the Piano Sonata in F sharp, Op. 78.

Had the new lockdown not intervened at the last moment, I’d have joined forces with the wonderful pianist Piers Lane for some narrated concerts this month – the one for the Barnes Music Society is now rescheduled for 16 January. The book is featured in the Up Close and Music Festival at the Fidelio Orchestra Café, Clerkenwell, now no longer in November 2020 but May 2021. Fidelio, after all, could scarcely be more appropriate.

- Immortal is published by Unbound, £10.99 (p/b), £5.99 (e-book), £19.24 (audiobook by Lamplight Audiobooks)

- More from Jessica Duchen on Immortal in this film from the Wigmore Hall

- Read more classical reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment