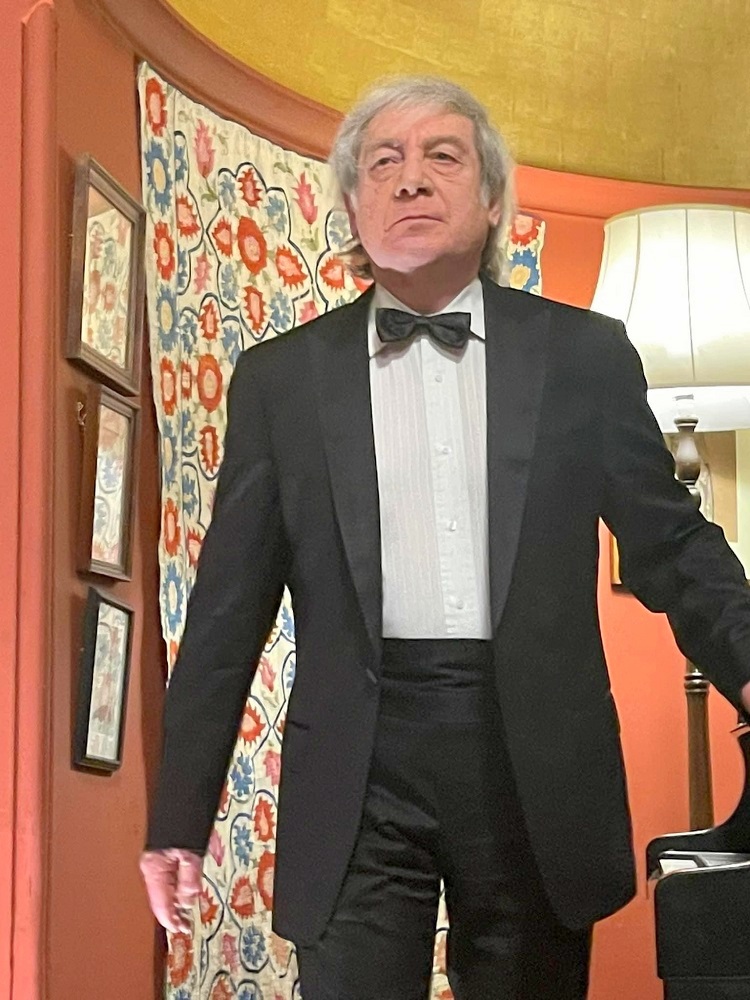

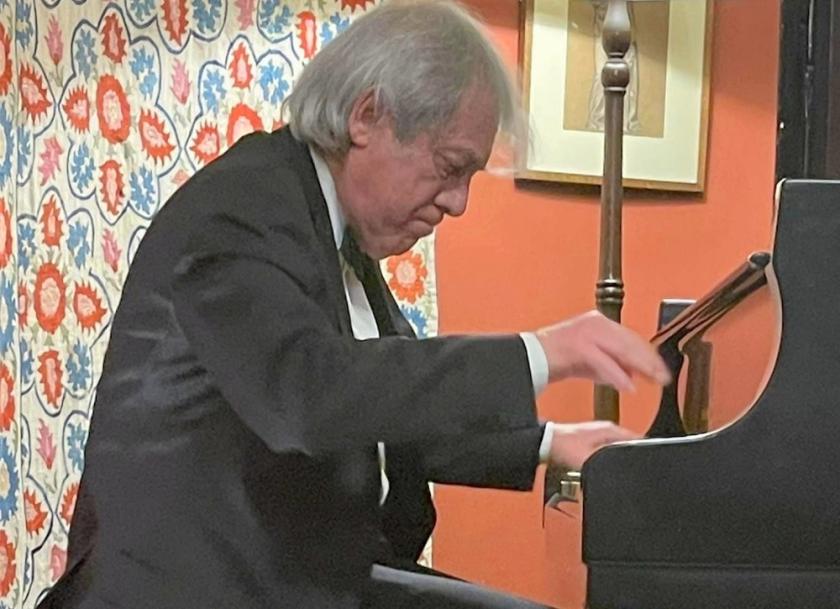

You can brush aside any problems septuagenarian pianists may have in the toughest repertoire, especially if they give you more than glimpses of why they’re legends in the first place. Those were frequent from the masterly Dmitri Alexeev, long inclined to prefer passing on wisdom to a new generation of pianists as Professor at the Royal College of Music and in his other home in Rieti over the treadmill of recital giving.

This was Alexeev's only London recital this season. Enriched by the extraordinary surroundings of the newly-restored Leighton House, and the fine acoustics of the big studio where he played under a golden dome like the apse of a church, it will never be forgotten.

Alexeev’s Schumann was revelatory. His default mode is unpedalled clarity, a weight and focus never overdone, but the range of colours in Waldszenen conjured so many images, even if not necessarily those Schumann had in his mind’s eye when he wrote this magical sequence. A phrase begun in clarity could melt into chiaroscuro; the robust quickly gave way to the ethereal, with a sense of the overall picture ensuring special connections between each piece. The Novelette Op. 21 No. 1 was for me the highlight of the whole concert, tailor made in its returning theme for Alexeev’s essential leonine quality, punctuated by more clarity for the secret raptures in between.

In the opening work of the recital, Mozart’s C minor Sonata K457, Alexeev highlighted the modernity, especially in the slow movement, and the seamlessness, with one impressive dovetailing between the second half of the first movement and its repeat. If overall the impression was more romantic than the objectivity which impresses in the interpretation of Alexeev’s near-contemporary, Elisabeth Leonskaja, that’s perfectly valid given such clear intentions.

In the opening work of the recital, Mozart’s C minor Sonata K457, Alexeev highlighted the modernity, especially in the slow movement, and the seamlessness, with one impressive dovetailing between the second half of the first movement and its repeat. If overall the impression was more romantic than the objectivity which impresses in the interpretation of Alexeev’s near-contemporary, Elisabeth Leonskaja, that’s perfectly valid given such clear intentions.

I’m indebted to the pianist for choosing a programme which highlighted a startling correspondence between Schumann’s uncanny “The Bird as Prophet” in Waldszenen and the time-stands-still theme which rounds off the first-movement exposition of Prokofiev’s colossal Eighth Sonata; both have mysterious arpeggiations on the upbeat. Bearing in mind that Prokofiev rings the changes on Schumann’s “Wehmut” (with its protestation that ‘I sing as though I were happy, yet no-one feels the pain, the deep sorrow in the song") in the middle movement of the Seventh Sonata, there may well be a poignant homage here too. Alexeev made its return in the finale absolutely mesmerizing, but got into a bit of trouble around its first appearance; he steered out of it impressively but then had to take the juggernaut of destruction in the development a bit too carefully. The real hair-raising excitement came in the finale, where the final charge to slamming home an ambiguous victory saw him released of the need to rein in. Too much has been said about outlawing Russian repertoire in the face of Ukraine's suffering, but the message here is one of a devastation, fear and nostalgia which can be felt by everyone in a profound Prokofiev masterpieces.  For contrast, the first encore gave us the dreamy opening of the Visions fugitives, yoked to the vintage Prokofievian spikiness of No. 10. If you count those separately, we got six encores: more Schumann (“Schlummerlied” from Albumblatter. Op 124 and the Intermezzo from Faschingsschwank aus Wien, a more straightforward Mendelssohn Song without Words (Op. 67 No. 2) and finally Granados’s Spanish Dance No 5, best of all in its utterly natural sway, seemingly effortless mastery again. Clearly the inspirational surroundings inclined Alexeev to carry on giving, and the audience (pictured above), including many of his students past and present, would have been happy with another half-dozen. But we’d certainly had our vision.

For contrast, the first encore gave us the dreamy opening of the Visions fugitives, yoked to the vintage Prokofievian spikiness of No. 10. If you count those separately, we got six encores: more Schumann (“Schlummerlied” from Albumblatter. Op 124 and the Intermezzo from Faschingsschwank aus Wien, a more straightforward Mendelssohn Song without Words (Op. 67 No. 2) and finally Granados’s Spanish Dance No 5, best of all in its utterly natural sway, seemingly effortless mastery again. Clearly the inspirational surroundings inclined Alexeev to carry on giving, and the audience (pictured above), including many of his students past and present, would have been happy with another half-dozen. But we’d certainly had our vision.

Add comment