Théodore Dubois: Musique Sacrée et Symphonique, Musique de chambre (Ediciones Singulare)

Théodore Dubois: Musique Sacrée et Symphonique, Musique de chambre (Ediciones Singulare)

Théodore Dubois is the sort of figure whose grave you'd expect to stumble upon in Père Lachaise Cemetery. For decades he was a senior figure in French music, teaching at the Paris Conservatoire for 35 years. Until, that is, his abrupt retirement in 1905, precipitated by his refusal to award the Prix de Rome to a young upstart called Maurice Ravel. Start dipping into this three-disc set, and you can understand why. Dubois's conservative style and impeccable manners place him very much in the 19th century. Debussy and Ravel must have terrified him. But there's a lot of fun to be had here. Approach the second disc with caution; Dubois's dreary and saccharine Messe Pontificale is technically sound but totally lacking in spark, though the shorter sacred pieces are more involving. A brief O Salutaris cheekily recycles a Beethoven slow movement.

Dubois's own Symphony No. 2 is a find, however. Its opening bars quote Mussorgsky. The heavier climaxes borrow heavily from Liszt and Wagner, though the prevailing mood remains fluffy and light. It's heard in a ripe performance from Hervé Niquet's Brussels Philharmonic. The earlier Symphonie française is played by the period-instrument Les Siècles under François-Xavier Roth. It opens a bit dourly but soon picks up, the scherzo making brilliant use of an obbligato celesta. The last movement's brassy joie de vivre doesn't pall. Dubois's Piano Quartet has a sublime adagio, and we also get the expansive, engaging Sonata for Piano. Production values are exquisite, the discs presented in a handsomely produced hardback book. It's one of an ongoing series generously funded by the Palazetto Bru Zane in Venice. Sleeve notes include entertaining excerpts from Dubois's journal, giving us his thoughts on Stravinsky's Le Sacre (“the most disagreeable and disordered-sounding mess”) along with some blackly comic musings written shortly before he died.

Grieg: Lyric Pieces Stephen Hough (Hyperion)

Grieg: Lyric Pieces Stephen Hough (Hyperion)

Grieg's complete Lyric Pieces would fill three discs, but Stephen Hough's recording is all that most of us will ever need; Hough's selection of 27 contains many of the best-known and a fair few ripe rediscoveries. Twenty-eight short pieces pass in the blink of an eye; each one with a distinct flavour, each one approached with utter sincerity and deep affection. Hough is one of the smartest, most intelligent of pianists, but his erudition serves the Grieg, not his ego. He opens his collection with the same “Arietta” with which Emil Gilels began his famous DG disc. Hough's swift, flexible approach is tougher but no less appealing. He's alive to Grieg in more melancholy mode; the “Berceuse”'s yearning intervals have real poignancy. And, sweetly, the recital ends with the last Lyric Piece of all, a gorgeous revisiting of the “Arietta”'s melody.

There's too much else to mention in full. “Butterfly” has a dazzling nonchalance. The tantalisingly-named “Erotikon” is a disappointing sober, sweet love song to Grieg’s wife Nina. Hough nails the “Elegy”’s elusive mood, while his “March of the Trolls” is brilliantly pointed and witty. I’d forgotten how modern-sounding “Bell Ringing” sounds, and “Homeward” is a blast. “Wedding Day at Troldhaugen” is crisp and sharp. This is the musical equivalent of a box of high-end chocolates, though one which you can happily consume without ill-effects. Beautifully recorded, Hough swapping his usual Steinway for the clearer sonorities of a new Yamaha.

Maxim Rysanov plays Martinů (BIS)

Maxim Rysanov plays Martinů (BIS)

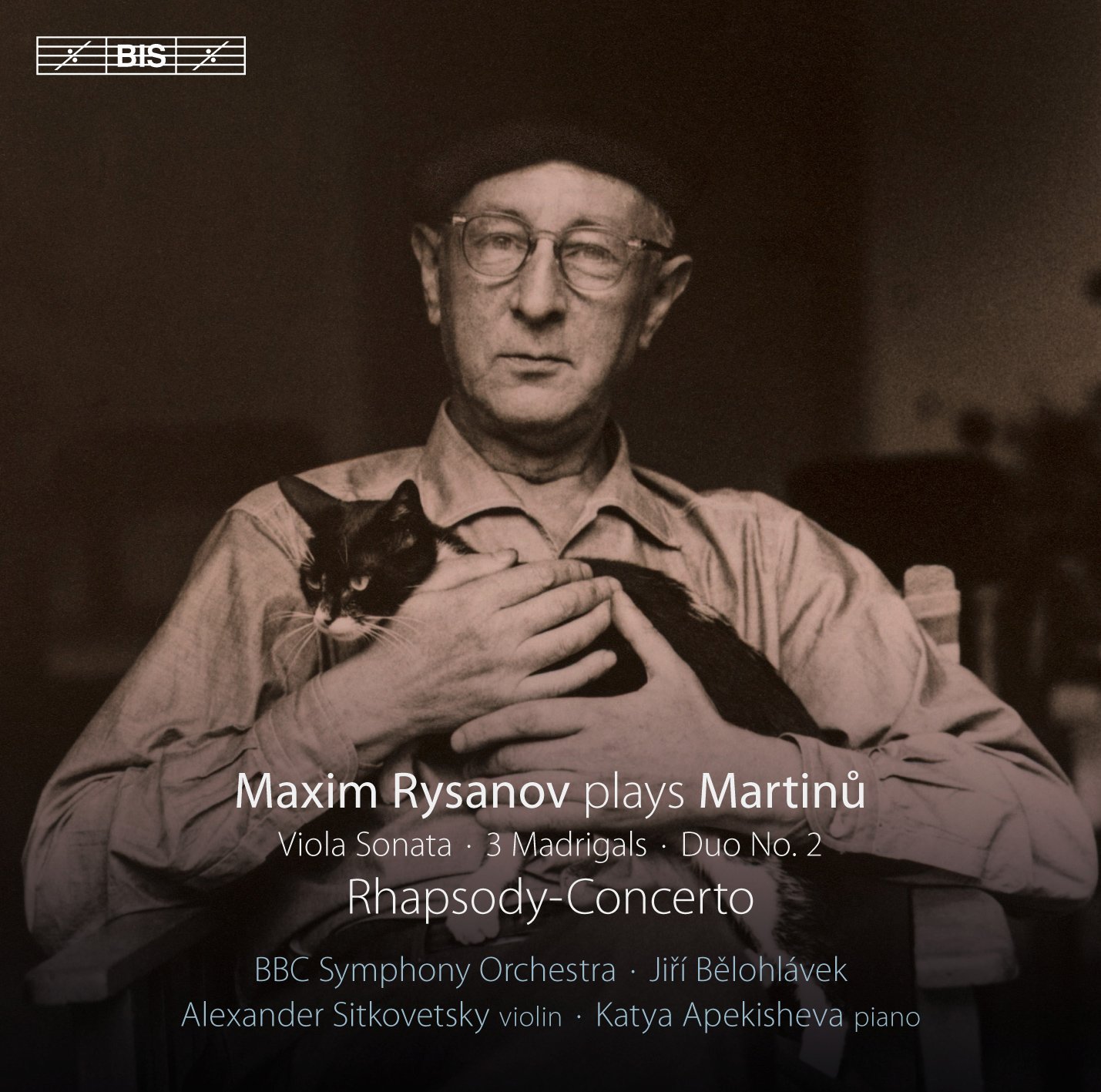

Bohuslav Martinů's concise Rhapsody-Concerto for viola and orchestra is a late work, written in 1952. He'd been through the mill, moving to the US from France to flee the Nazis in 1941, and returning to Europe in 1953. Not that you'd detect that anything was amiss from the music, which is as radiant and euphonious as anything Martinů ever wrote. And so well-written for its soloist; I'm convinced that this is one of the greatest viola concertante works ever written. That Jiří Bělohlávek draws beautifully translucent playing from the BBC Symphony shouldn't surprise anyone, but Maxim Rysanov's playing is outstanding – I've never heard a viola sing quite like this. If Rysanov's sotto voce statement of the hymn-like tune a few minutes before the close doesn't induce shivers, you've no heart. What a glorious finish this is, the quiet side drum a pleasing touch of grit just seconds before the work ends.

But it's only 20-minutes long, so we get much more. Martinů's Three Madrigals for violin and viola are brilliantly realised, the music alternating between sharp counterpoint and writing which occasionally suggests a full string orchestra, despite there only being two players. BIS's notes suggest that the three movement Duo No.2 for violin and viola is less popular as it's a less accomplished work. You have to disagree; the first movement's duets are dazzling, and the piece leaves you wanting more. Rysanov is joined by pianist Katya Apekisheva in the Sonata for Viola and Piano. The opening chords ring out like church bells, Rysanov's ensuing solo like an incantation. More sombre than the other pieces on the disc, it's still an uplifting listening experience. A peach of a disc, containing something for everyone – not just viola players and Martinů fans. Entertaining cover photo, too.

Add comment