Classical and Opera 2013: A Year of Anniversaries | reviews, news & interviews

Classical and Opera 2013: A Year of Anniversaries

Classical and Opera 2013: A Year of Anniversaries

Three of the team choose their best of the year - and there was a lot of it

Which musical calendar year isn’t laden down with composer commemorations, too often a pretext for lazy and unimaginative planning? The last 12 months, with Verdi, Wagner and Britten as the birthday boys (in case you failed to hear), have raised the stakes.

It looked on paper as if the BBC Proms were going for the obvious: all the major Wagner operas except The Flying Dutchman and The Mastersingers in semi-staged versions.The execution exceeded everyone’s wildest hopes (there, I’ve snuck in a collective top choice already). Now, it seems, is the time when opera is becoming the designer’s provenance, clutter overwhelms clarity and the crucial one-to-ones of Wagnerian music-drama, the personenregie as another useful German compound noun has it, can all too easily be overlooked. Semi-staging director Justin Way’s practical framework and the bonding of great singers used to working with each other pulled into focus what I, at least, really want from the Wagnerian experience – and that comes from a fierce defender of the full experience against knee-jerk traditionalists who wonder why we have productions when opera in concert seems to work so well (below, Daniel Barenboim's speech to the audience at the end of his Proms Ring cycle, photo by Chris Christodoulou).

While Verdi did much less well in the UK - a keenly anticipated Sicilian Vespers at the Royal Opera House delivered only on some fronts - the Britten 100 experience capped the lot. Sure, you could suffer from overkill if you were tuned exclusively to Radio 3, but otherwise you could take your pick, hear works unfamiliar to you – and in the enormous output of our greatest composer after Elgar, another devoted internationalist, there was always going to be something – and choose to follow all or any of the operas (how very satisfying, for example, that in London or thereabouts this autumn you could go from Paul Bunyan to Albert Herring via Peter Grimes and The Rape of Lucretia in chronological sequence). Funding from the Britten Estate and careful planning helped, and children up and down the country performed music that would usually be deemed too difficult, just as the composer had always intended: his blueprint for education may at last be coming back into fashion

While Verdi did much less well in the UK - a keenly anticipated Sicilian Vespers at the Royal Opera House delivered only on some fronts - the Britten 100 experience capped the lot. Sure, you could suffer from overkill if you were tuned exclusively to Radio 3, but otherwise you could take your pick, hear works unfamiliar to you – and in the enormous output of our greatest composer after Elgar, another devoted internationalist, there was always going to be something – and choose to follow all or any of the operas (how very satisfying, for example, that in London or thereabouts this autumn you could go from Paul Bunyan to Albert Herring via Peter Grimes and The Rape of Lucretia in chronological sequence). Funding from the Britten Estate and careful planning helped, and children up and down the country performed music that would usually be deemed too difficult, just as the composer had always intended: his blueprint for education may at last be coming back into fashion

Early music fans were well catered for, as usual, in a host of festivals, but it was the 20th century path selectively followed by Alex Ross in his phenomenally successful and wide-reaching book The Rest is Noise, opened out to a large and predominantly youthful audience at the Southbank, which proved the smash hit of the year. From the closing scene of Strauss's Salome and Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius to John Adams’s El Niño, much of it was mainstream but as we moved into the post-1945 era the juxtapositions became ever more outlandish and astonishing. With attendance never falling below the 1800 mark, a new listenership had been hooked. Can the concert world now manage to build on that?

Here three of theartsdesk’s classical and opera team reflect on a real cornucopia of a year: Alexandra Coghlan and I look at the live scene, while Graham Rickson – who has also caught the ongoing high standards of Opera North in Leeds – picks the best of his CD listening year.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN

My classical 2013 has been more than usually dominated by opera, but looking back very few of its highlights have come from the obvious sources. For every high profile Sunken Garden that fell flat (a serious contender for my dud of the year) there have been a handful of quirkier offerings that have genuinely provoked and delighted.

My ears are still squirming at the memory of Sciarrino’s vocal writing in The Killing Flower, staged by Music Theatre Wales at the Linbury. At once utterly original and instinctively natural, these extraordinary melody-convulsions were a revelation. MTW had the stand-out season of the year, pairing the Sciarrino with a revival of Turnage’s Greek. The ferocity and wit of the composer’s early work hit harder than ever, and I can’t have been the only one yearning for the composer to recapture his angry young man energy and reclaim his place as the Tony Harrison of classical music.

In Britten’s anniversary year there were always going to be some stand-outs, and none more so than the insanely ambitious Grimes on the Beach (rehearsal pictured above for the BBC by Robert Workman). Site-specific can surely never have been as literal as these performances of Britten’s masterpiece in the landscape and on the very shingle that rustles and pulses through the music. The wind howled and the North Sea chilled, but it only added to the heart-swelling intensity of it all.

Glyndebourne’s revival of the Michael Grandage Billy Budd was another reminder that sometimes tradition and simplicity can trump technological innovation, generating tremendous tension and emotion from Britten’s difficult opera. A concert performance of The Turn of the Screw by Richard Farnes and the LSO completed my triptych of top Britten, with Andrew Kennedy delivering a controlled and magnificently chilling performance as Peter Quint, and particularly exquisite playing from the wind.

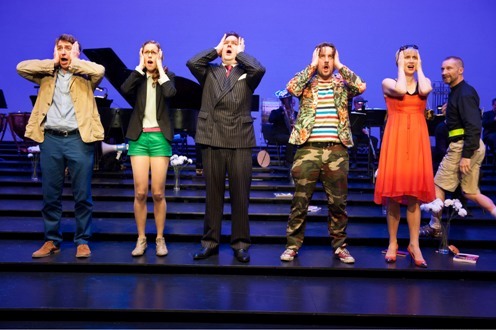

Another concert-performance opera that impressed was Ex Cathedra’s Late Night Prom. Reprising their 2012 staging of Stockhausen’s Mittwoch aus Licht, the group gave us the lively Welt-Parlament section, persuading a casual Proms crowd to engage with this bit of musical madness, delivering one of the most technically precise and dramatically lively evenings of the year.

Opera didn’t have it all its own way though. At the Wigmore Hall the first concert of period ensemble L’Arpeggiata’s residency (the group pictured left) had me eager for the second and third, getting a staid crowd dancing and tapping to their infectious rhythms and riffs. There’s nothing starchy or precious about this early music group, who bring the best of world, folk and classical music together in joyous fusion.

Opera didn’t have it all its own way though. At the Wigmore Hall the first concert of period ensemble L’Arpeggiata’s residency (the group pictured left) had me eager for the second and third, getting a staid crowd dancing and tapping to their infectious rhythms and riffs. There’s nothing starchy or precious about this early music group, who bring the best of world, folk and classical music together in joyous fusion.

If I had to pick one event though to top all others, it would have to be my first live experience of the Music For Youth Schools’ Prom at the Royal Albert Hall. This massive event, stretched across three nights, showcases the skills of children from across the country, ranging from 7-year-olds with their 1/14-size violins and recorders, to polished pop acts from teenagers. Our X-Factor age has devalued all superlatives, but these kids were truly magnificent – confident, happy, creative, and above all loving making music. And that’s what it’s all about really, isn’t it? Whether you are Daniel Barenboim or a Grade 2 clarinettist – if we don’t feel the joy, then no amount of technique can compensate.

DAVID NICE

Too many choices here, but what the hell – it’s been a phenomenal year. A is for Adams, John (pictured below by Kevin Leighton), who provided a beginning, a middle and an end. Even before the Southbank’s festival of 20th century music had begun, the Barbican was fighting back with a miniresidency from the composer as much-improved, bendy-kneed conductor. The three concerts revealed to me the beauty of the great American’s Debussy arrangements – with perhaps his favourite soprano, Dawn Upshaw, still on fine form – the exultation of Shaker Loops with the LSO Strings at St Luke's alongside the complexity of his String Quartet which sent me in pursuit of a score and time to absorb it and the comedy-with-depths of his Beethoven homage Absolute Jest.

At passion time came the daring new leaps into the dark of Adams' latest epic, The Gospel According to the Other Mary, where Peter Sellars’ familiar semaphoring felt meaningful as his original visual overload for the nativity oratorio El Niño at the time of its 2000 premiere had not. Come December, Vladimir Jurowski's magnificently cast but image-chaste performance took measure of the work's purely musical greatness and decided it for me: another Adams masterpiece, no doubt about it.

At passion time came the daring new leaps into the dark of Adams' latest epic, The Gospel According to the Other Mary, where Peter Sellars’ familiar semaphoring felt meaningful as his original visual overload for the nativity oratorio El Niño at the time of its 2000 premiere had not. Come December, Vladimir Jurowski's magnificently cast but image-chaste performance took measure of the work's purely musical greatness and decided it for me: another Adams masterpiece, no doubt about it.

The comparison with Britten’s fertility and dangerous drive to cover new territory is beginning to seem not too hyperbolic. Certainly Adams is the only composer until this year who, in my experience, has written an opera I've experienced at, or close to, its premiere so obviously destined to last (Nixon in China back in 1986; James MacMillan’s The Sacrifice as well as a couple of Turnage stage works merit an honourable mention). Adès is often cited as Britten's true successor, but no way, as yet, for me, and George Benjamin’s Written on Skin was my biggest disappointment this year: refined musical language, yes, and first-class realization, but lumpy, often repetitive pacing which led to a denouement about which I couldn’t care less. The cold characterizations in a horrid story with a risible libretto by Martin Crimp nailed the coffin shut fairly fast; though others vehemently disagree. Whereas I cried with laughter at the plate-smashing pièce de resistance of Gerald Barry’s endlessly resourceful The Importance of Being Earnest and enjoyed the contemporary Linbury staging (pictured below by Stephen Cummiskey) alongside a razor-sharp orchestra rife with Stravinskyan punch in wind and brass more than my colleague Igor Toronyi-Lalic, who’d been lucky enough to see the Barbican premiere.

Conversely to the Skin experience, I warmed to Kasper Holten’s emotionally intelligent Royal Opera take on Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin where others found only artifice and obscurity; seeing the recently released DVD confirmed the hold it had on me, and Robin Ticciati’s conducting seemed more settled and nuanced. Ticciati's partnership with Mitsuko Uchida in Mozart, followed by an original take on Dvořák's Fifth Symphony, fulfilled the promise of an Enigma Variations and had me hoping that he, and not the much-touted Rattle, might take over the London Symphony Orchestra reins from Gergiev (the jury's still out). But the Elgar was only half of a concert which had earlier seen Vengerov go badly off piste in the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, and some of my other highlights this year have stood out in curate’s-egg programmes: Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s deeply felt, supple ideals of Prokofiev interpretation in the Fifth Symphony with the Rotterdam Philharmonic at the Proms and the Seventh with the LPO later at the Festival Hall.

Conversely to the Skin experience, I warmed to Kasper Holten’s emotionally intelligent Royal Opera take on Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin where others found only artifice and obscurity; seeing the recently released DVD confirmed the hold it had on me, and Robin Ticciati’s conducting seemed more settled and nuanced. Ticciati's partnership with Mitsuko Uchida in Mozart, followed by an original take on Dvořák's Fifth Symphony, fulfilled the promise of an Enigma Variations and had me hoping that he, and not the much-touted Rattle, might take over the London Symphony Orchestra reins from Gergiev (the jury's still out). But the Elgar was only half of a concert which had earlier seen Vengerov go badly off piste in the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, and some of my other highlights this year have stood out in curate’s-egg programmes: Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s deeply felt, supple ideals of Prokofiev interpretation in the Fifth Symphony with the Rotterdam Philharmonic at the Proms and the Seventh with the LPO later at the Festival Hall.

Perfect all through, on the other hand, were Stephane Denève’s French programme with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, getting a difficult Poulenc ballet suite exactly right, at least half thanks to narration by the brilliant Stephen Mangan, before culminating in a student-led Ravel L’enfant et les sortilèges, and above all Vladimir Jurowski's father, German-based Michail, giving what he regarded as his proper UK debut with the delirious but cumulative-impact collage wildness of Schnittke’s First Symphony. That was my biggest discovery in a year of hearing so many works in concert for the first time. The event - perhaps "happening" was more like it - also made me sit up and listen afresh to a work I thought I didn't care for, Lutosławski's Cello Concerto, in an electrifying theatrical narration by the extraordinary Johannes Moser.

I hadn’t even heard Britten’s Noyes Fludde live before; its Tewkesbury Abbey performance designed and part-directed by the brilliant and musically astute children’s illustrator James Mayhew culminated in an ensemble of Wagnerian breadth.The context, a pioneering Cheltenham Music Festival, was the first to give another anniversary boy, Poulenc, his proper due. Britten's Gloriana I’d seen a few times before, but not as Richard Jones imagined it in a perfectly followed-through new concept at Covent Garden. I may not have got to Aldeburgh this year, but I could hardly regret missing the centenary weekend in Britten’s home town when in London there was probably the best-cast Albert Herring ever: not a flaw in the gallery of the grotesque and the deeply human revolving around Andrew Staples’ great comic turn as the greengrocer’s boy who busts out.

I hadn’t even heard Britten’s Noyes Fludde live before; its Tewkesbury Abbey performance designed and part-directed by the brilliant and musically astute children’s illustrator James Mayhew culminated in an ensemble of Wagnerian breadth.The context, a pioneering Cheltenham Music Festival, was the first to give another anniversary boy, Poulenc, his proper due. Britten's Gloriana I’d seen a few times before, but not as Richard Jones imagined it in a perfectly followed-through new concept at Covent Garden. I may not have got to Aldeburgh this year, but I could hardly regret missing the centenary weekend in Britten’s home town when in London there was probably the best-cast Albert Herring ever: not a flaw in the gallery of the grotesque and the deeply human revolving around Andrew Staples’ great comic turn as the greengrocer’s boy who busts out.

It’s tempting just to reel off a list of great performers: among quartets the Jerusalem and Belcea, commanders of fire and ice both (and I’m grateful to the Belceas for making me fall head over heels in love with Britten’s First Quartet); among singers soprano Anne Schwanewilms making Schumann's Op. 39 Liederkreis my favourite song-cycle - and another Strauss-centric diva, Renée Fleming, was at her silvery best in his last opera Capriccio; among pianists Imogen Cooper, Yevgeny Sudbin, Boris Giltburg, Boris Berezovsky, Daniil Trifonov and above all a revelatory debut from the brilliantly-programming contemporary champion Mei Yi Foo (pictured above by Kaupo Kikkas); and Lisa Batiashvili supreme among violinists, plumbing the depths of Sibelius’s Violin Concerto with Sakari Oramo at the Proms. But unquestionably the greatest star of them all, shedding her years and her infirmity as she ran the gamut of Broadway, cabaret and Cabaret alike, was Liza Minnelli, again courtesy of The Rest is Noise festival. As we ended up standing for number after number in, who’d have thought it, the Festival Hall, I was delighted that Vladimir Jurowski in the seat next but one to me was as enthusiastic as anyone. Great artistry comes in any shape or form, and putting across a song doesn’t come more dynamic than that.

GRAHAM RICKSON

I began listing candidates for an end-of-year "best of" among the CDs of 2013 months ago, and reducing the shortlist to manageable proportions has been tough. In amongst the endless reissues, the disturbingly cheap box sets and the naff crossover discs, there’s a huge amount of interesting material still being released. The independent labels continue to be the boldest, and it’s reassuring that people still seem prepared to buy physical CDs, rather than soulless downloads. Recorded music will never be a substitute for live performance, but the experience will be more potent if you listen to CDs the old-fashioned way - through decent loudspeakers, sat on a comfy sofa. Not as an MP3 file, through cheap headphones or on a car stereo.

My favourite CD of the year remains the Mythos Accordion Duo’s remarkable transcription of Stravinsky’s Petrushka (disc pictured left), so bold and colourful that you can’t imagine needing to hear the orchestral version again. I also enjoyed Sergio Tiempo and Karin Lechner’s scintillating, theatrical reading of Federico Jusid's Tango Rhapsody – arguably not great music, but heard (and seen on the bonus DVD) in a great performance. Antonio Pompa-Baldi playing idiomatic piano transcriptions of songs by Edith Piaf and Poulenc was a delight, and Hindemith’s sublime Christmas fairy tale Tuttifäntchen was an unexpected surprise, one which a colleague deemed worthy of compare with Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel. An equally arresting discovery was a long-forgotten Cinderella ballet score by the Swiss composer Frank Martin – a fascinating alternative to the better-known Prokofiev version.

My favourite CD of the year remains the Mythos Accordion Duo’s remarkable transcription of Stravinsky’s Petrushka (disc pictured left), so bold and colourful that you can’t imagine needing to hear the orchestral version again. I also enjoyed Sergio Tiempo and Karin Lechner’s scintillating, theatrical reading of Federico Jusid's Tango Rhapsody – arguably not great music, but heard (and seen on the bonus DVD) in a great performance. Antonio Pompa-Baldi playing idiomatic piano transcriptions of songs by Edith Piaf and Poulenc was a delight, and Hindemith’s sublime Christmas fairy tale Tuttifäntchen was an unexpected surprise, one which a colleague deemed worthy of compare with Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel. An equally arresting discovery was a long-forgotten Cinderella ballet score by the Swiss composer Frank Martin – a fascinating alternative to the better-known Prokofiev version.

In a year full of new Britten releases, the pick for me was James Ehnes’s searching reading of the Violin Concerto, its haunting close rarely sounding so ambivalent. A searching Mompou anthology from pianist Arcadi Volodos beguiled, and orchestral thrills came courtesy of Riccardo Chailly’s sleek Brahms symphonies set with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Chailly gives us lean, urgent performances, captured in glorious sound, with some fascinating extras on the third disc.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment