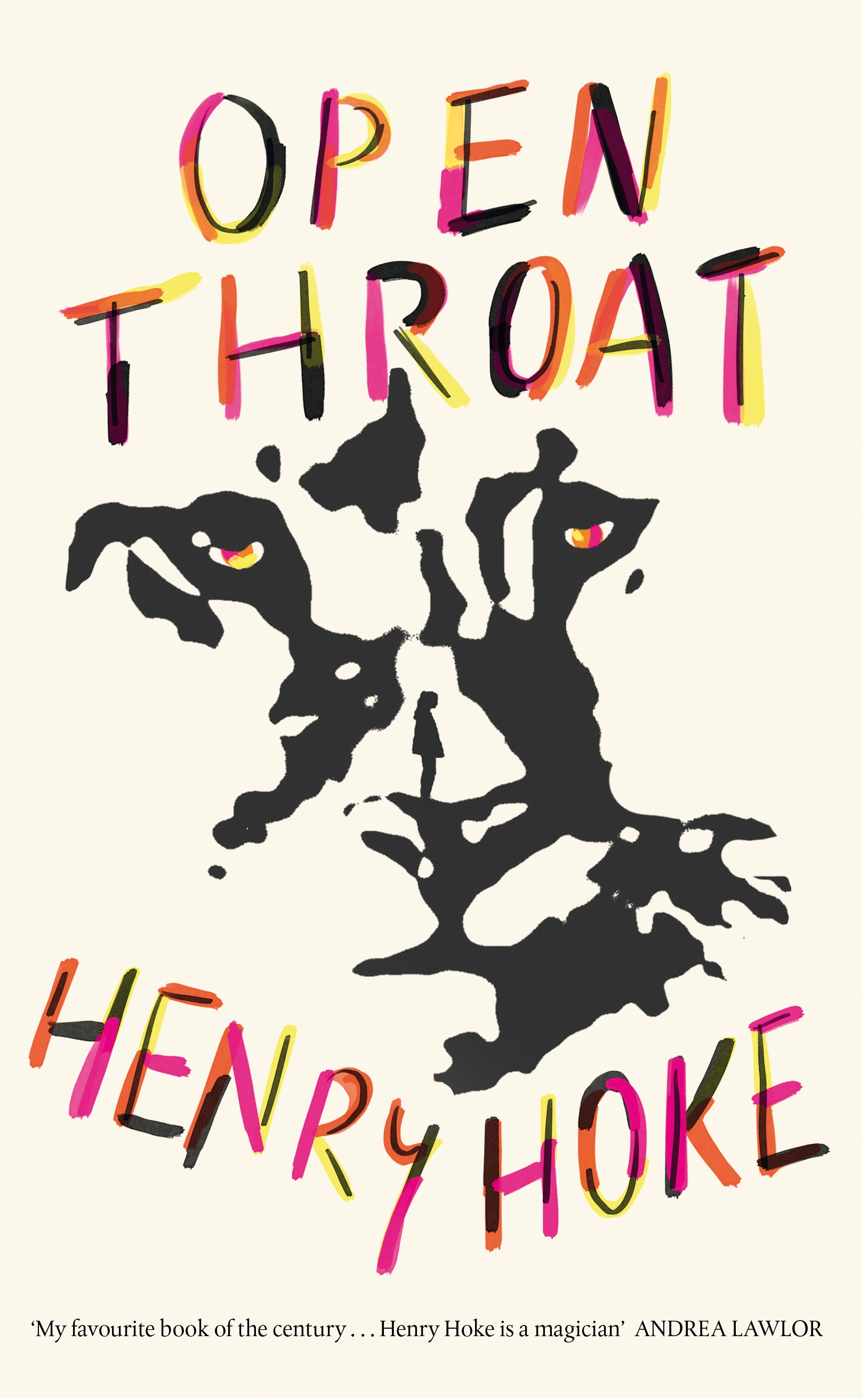

I approached Henry Hoke’s fifth book, Open Throat, with some trepidation. A slim novel (156 pages), it seemed, at first glance, to be an over-intellectualised prose-cum-poetical text about a mountain lion.

But the novel was so much more: an odd but wryly astute social commentary from an animal that has been forced to move from nature to where the humans are – and he doesn’t wholly hate it. It’s also (loosely) based on the famous P-22 mountain lion, who also lived in LA, and whose story at times intersects with that of the protagonist of Open Throat.

The lion, whose name, we are told, is unpronounceable to humans, lives in the barrens above LA (or as he hears it, "ellay"). From hideouts in the brush and trees he listens to the conversations of walkers. He begins to understand them, but there are points at which he can’t quite bridge the gap. He hears some hikers discussing their therapists. He’d quite like a therapist, he muses – perhaps he’ll find one, drag it into a cave, and force it to give him weekly sessions.

In these moments, the line between animal and human blurs. The lion has daddy issues: his father killed his mother and then drove him off their territory. He fell in love with another male lion who seemed to reciprocate his feelings without being able to communicate in a way that humans would see as valid. They shared kills and seemed to have companionship, but then his paramour crossed the "long death" (likely an expressway) and was run over – something we only see when the protagonist crosses the long death himself and enters the human landscape. These person-like descriptions of the lion’s inner life can feel like a stretch at times, but they allow Hoke to comment sharply on humanity’s intervention in the land around us.

In these moments, the line between animal and human blurs. The lion has daddy issues: his father killed his mother and then drove him off their territory. He fell in love with another male lion who seemed to reciprocate his feelings without being able to communicate in a way that humans would see as valid. They shared kills and seemed to have companionship, but then his paramour crossed the "long death" (likely an expressway) and was run over – something we only see when the protagonist crosses the long death himself and enters the human landscape. These person-like descriptions of the lion’s inner life can feel like a stretch at times, but they allow Hoke to comment sharply on humanity’s intervention in the land around us.

Open Throat’s examination of the worst parts of the Anthropocene can, at points, also feel laboured, and even a little proselytising (though perhaps this is inevitable when the issue is so horribly close at hand). The lion watches his home go up in flames when two characters torch a town full of homeless people – the people to whom he himself feels closest. The fire then engulfs the hills where the lion lives, forcing him to hide out in the house of someone who appears to be famous (although we are never told for what). There’s a clear judgement here of man’s abuse of power, both environmentally and emotionally.

It’s laboured because these themes are both obvious and uncomfortable, a truth that never comes out well in books because, although we know it, very little is being done to correct the imbalance. Hoke is perhaps more successful, although no less obvious, when the lion overhears the petty and ridiculous conversations of hikers and contemplates eating them. He witnesses their attempts (and failures) to connect, their pettiness, and the contrast with those in the tent town who are just trying to survive.

The lion is given enough understanding to be able to comment on what he sees, but not enough to be able to escape humanity’s degradations. He stumbles into what appears to be a zoo and eats one of the captive animals, seeing others that are almost like him but that smell different, miserable and trapped. Open Throat’s musings are interesting and, at times, heartbreaking, though they remain on the nose. Perhaps, though, the obviousness of the lion’s suffering should serve as a lesson to us. If this quasi-allegory feels overbaked, it’s because it’s saying something we’ve all heard a thousand times before, but haven’t yet listened.

- Open Throat by Henry Hoke (Picador, £14.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment