Akram Khan is unexpectedly softly-spoken. Acknowledged as a truly great dancer, he's a master of the classical Indian Kathak form that he trained in, and also supremely gifted at blending it with other movement vocabularies to create a personal signature style of elemental force, He creates hypnotic worlds in his pieces, with the kind of magnetic stage presence that draws you in so completely, you're often a little amazed, when the curtain drops, to find yourself still a perfectly ordinary human being sitting in theatre seat. Somehow, I expected this aura and gravitas to be matched by stentorian tones, and so the first time I heard Khan speak (which he often does, in his dance pieces), his soft voice and gentle, warm manner of speaking, took me by surprise.

But gentleness and warmth are in fact characteristic of Khan, who not only shares the stage far more often than taking it alone, but always pays generous tribute to his collaborators, whose illustrious ranks have included composers Jocelyn Pook and Nitin Sawhney, ballerinas Sylvie Guillem and Tamara Rojo, and actress Juliette Binoche. His new show, TOROBAKA, receives its UK première at Sadler’s Wells on Monday 3 November, and yet again sees Khan choosing to choreograph with, and perform alongside, a great dancer from another tradition, this time the highly original flamenco star Israel Galván. So when we spoke on the phone last week, I started by asking him about this new collaboration.

Why did you want to work with Israel Galván?

I didn’t really want to work with flamenco at all actually. I didn’t like the idea of Kathak and flamenco. My guru (Sri Pratap Pawar) did a nice version but apart from that I’ve never seen one that really made me feel that it was going deeper than two forms sharing symmetry: it was very superficial for me. So I didn’t really like the idea of it, but I went to see Israel Galván, because they said you, know, see him and see what happens. And I thought, wow this is an artist who has the key to de-constructing flamenco and reconstructing it in his own way. I thought, if I ever wanted to do flamenco and Kathak, this would be the artist I wanted to do it with.

Ismene Brown has said in a review on this site that he’s wired differently from other people.

It’s like David Lynch and Stanley Kubrick are having a conversation in his head. We went to see each other perform and we liked what we had seen and we went into the studio and we started playing a lot, just exchanging movement vocabularies, and that was really fun. That was how the whole thing began, just the two of us in the studio.

Did the concept for the piece came out of that playing?

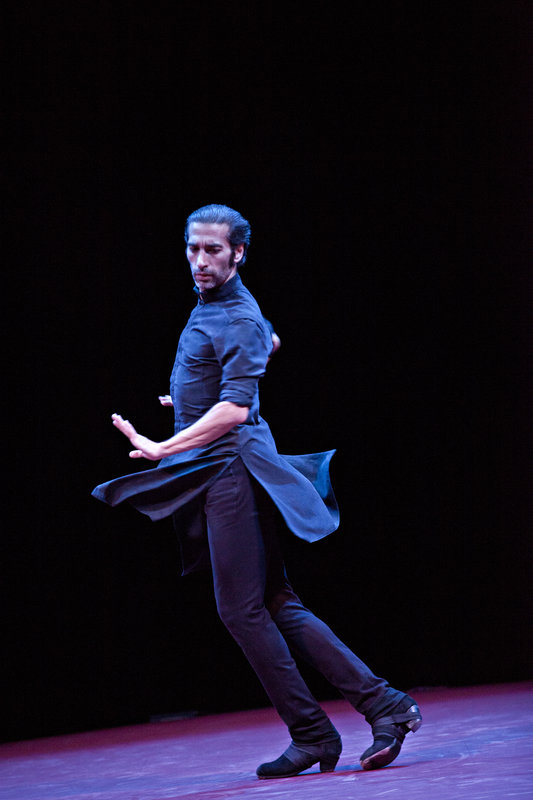

The concept came out of conversation, but it was a little bit later. It was the beginning of this year when we said now we have to stop playing, we have to grow up and we have to make decisions. It was an interesting challenge, because he has his own world that he creates (pictured right: Israel Galván), and I create my world, and we were looking for a new world. And the funny thing is, just by the two of us being in the studio it was already creating a new world: we didn’t have to look for something external to create. It was already happening organically.

The concept came out of conversation, but it was a little bit later. It was the beginning of this year when we said now we have to stop playing, we have to grow up and we have to make decisions. It was an interesting challenge, because he has his own world that he creates (pictured right: Israel Galván), and I create my world, and we were looking for a new world. And the funny thing is, just by the two of us being in the studio it was already creating a new world: we didn’t have to look for something external to create. It was already happening organically.

Michael Hulls, who’s our lighting designer, saw the material and thought there was something really strong there and [said] just have confidence in what you’re doing. And so in a sense we didn’t search anywhere, we just looked at the flamenco and Kathak vocabulary.

We were interested in origins, really ,and we were imagining what flamenco would be like before it was flamenco and Kathak was like before it was officially known as Kathak. We realised that a lot of the vocabulary or inspiration comes from nature, from animals. So that’s why the title has toro, for the bull – Spain - and baka the cow, which is India. We created our own idea of what the material would be like in its primitive stage. It’s very primal, let’s say, but it’s extremely sophisticated rhythmically, mathematically – musically.

He shared with me material that was taught him by his master on a chair, and I learned that choreography and then I gave him material that I’d learned from a friend of mine, Kathak traditional material, and he learned it. As we exchanged it, we were very clear that I wasn’t going to show I was a flamenco dancer [because] that would be a insult to flamenco, and he wasn’t going to show he was a Kathak dancer. What we felt was important was, how do I do the material he’s given me which is rooted in flamenco and transform it in a way which no flamenco dancer could do, only I could do? And the same thing for him. So in a way it’s not flamenco what I’m doing, it’s something that belongs to me - but the source is from him. And vice versa. What you see looks like flamenco, but is not flamenco.

How do you feel about flamenco now? What does it mean to you? What have you learned from Israel?

I've learned a lot. He’s really a master of what he does, and what I’ve learned is his logic of being illogical. As I’ve said, his brain is wired one half David Lynch and the other [half] Stanley Kubrick - so you can imagine what world he creates. In a sense, I’m always trying to find clarity and balance within chaos, and he’s always trying to destabilise that, to find chaos within the clarity that I create. That energy is fascinating.

That’s something about him, perhaps, rather than flamenco per se?

Yeah, it’s more about him. I don’t do Kathak in the Kathak way and I don’t think he does flamenco in the flamenco way. It’s very specific to us, it’s our way of doing things.

It sounds like the ideal kind of collaboration. Collaboration does seem to be a habit of yours – more often than not, we see you sharing the stage with another artist of equal stature. Musicians, of course, but also Sylvie Guillem, Juliette Binoche, Fang-yi Sheu. What is it about that process, that dynamic that attracts you?

I like to exchange. I get bored with myself very quickly. The only time I was not bored was doing DESH [Khan’s autobiographical solo piece] but then I had a lot of support from all the collaborators. They were not performing with me on stage, I was alone on stage, but I felt there was something we could exchange and share - I didn’t feel alone.

It was interesting working with Israel. I think it was his first collaboration with another choreographer in his career, so it was fascinating to find a dialogue, a common world that we could communicate with.

I had a rehearsal director who was integral to the work. He’s Spanish and he studied flamenco when he was a teenager and he studies Kathak with me now and he knows my work very well. So he was able to be the bridge in a sense, because language was difficult - Israel doesn’t speak much English and I don’t speak at all Spanish, so we had to find another way of communicating.

And that works through dance?

And that works through dance?

It works up to a point, but you need to be able to talk about ideas. The thing about this pieces is, it’s not like DESH, it’s not thematic heavy. It’s purely about movement vocabulary and the two different cultures it comes from. But I think it’s more than the two [original] cultures because we kind of make it our culture; something that we created in the studio by being together (pictured left, Khan and Galván). It’s very specific and unique to us without it being heavy on theme or religion or country or identity.

You are usually drawn to storytelling in your work, though, aren't you?

My form of training, Kathak, means to tell stories, so it’s literally a storytelling dance form. I’ve always liked to tell stories, whether they’re true or not. I just like to talk with my body.

You talk with your mouth too, which I like about your pieces: you’re good theatre as well as good dance.

That’s because I worked with Peter Brook and that had a huge impact on me when I was a kid. I had more theatre experience as a kid than dance. I was training in dance but I was not so submerged in that world as I was in theatre. I toured with Peter Brook for two years doing the Mahabharata, so working with those great theatre actors rubbed off a little bit on me - not their talent, but experiencing that level of theatre work, and their words.

But in this piece it’s not that at all, we use our voices, but it’s predominantly through our bodies.

Turning to another dance form now, I wanted to ask about your experience of working with ballet. You’ve said about working with Sylvie Guillem that classical ballet was attractive to you, but it was in Dust earlier this year that you worked with a ballet company (English National Ballet) for the first time.

I’ve always said no to it. I’ve always stayed away from ballet companies; I never like their intent. Or I didn’t like their scheduling, put it that way. I mean, I’m not going to work with ballet material and put different sequences of ballet vocabulary [together]. I wanted to explore the ballet body and the ballet vocabulary with my knowledge, and that takes time. So you know when Paris Opéra asked me, years ago, and other ballet companies, somehow I didn’t do it. I’m not a machine: I want it to be a process that transforms from within. I don’t just want to come and create material on their bodies and use their great ability and then, you know, wash my hands and [say] there’s your piece. That doesn’t work for me, so I always demand a lot of itime. It’s not always me saying no - sometimes they just can’t do it; it doesn’t fit with their schedules.

So when I met Tamara [Rojo] and she approached me, I thought this is the person that I would say yes to. She’ s really visionary and she said, tell me what time you need and we’ll make it happen. I love her spirit and what she’s willing to do with the company. She’s willing to take risks.

The atmosphere of the company seems to be really positive and exciting under her direction.

She’s wonderful. She’s a dancer, so she understand the dancers’ needs, but she’s also the artistic director. She has an amazing ability to know what is needed [for the company] and also to be sensitive to the dancers’ needs. That balance is really important.

The two of you had a fantastic energy in your duet in Dust (pictured right). Do you have plans to dance with her again?

The two of you had a fantastic energy in your duet in Dust (pictured right). Do you have plans to dance with her again?

I would love to. I’m not sure whether I’m going to do Dust when it comes back to London, but I’m doing it in Japan. I’m having a son in January - I already have a daughter - so my schedule is going to be a a little more tricky; time is going to be less and less. I would love to dance with her [again]; I so enjoyed dancing with her. She’s very generous and sensitive, and also connected.

Going back to Israel – Israel and I are terrified of each other! We have so much respect for each other, and I don’t mean that in a light way, I mean that we are literally shaking before we enter the stage, we freak out – me even more [than him]. But the funny thing is, when we enter the stage, the second we enter, both of us shift somewhere internally and we click into the present; we’re not in the past and we’re not in the future. What we fear before getting on stage is the future - we’re afraid of what could go wrong and the second you step on stage you become completely connected to the present. That’s a real power we have with this relationship. And I have that with Tamara too: when we’re on stage we’re very much in the present. That is very important for us.

This talk about fear reminds me of the story you tell about starting to work with Sylvie Guillem on Sacred Monsters – that the first thing she said to you was “I’m nervous.”

Israel was nervous simply because I think he’s not performed with another man before and you know, in flamenco that’s really a challenge. It’s interesting because he came in to kill me, to stab me to death, and I don’t mean that unkindly, I mean that seriously. He said to me, I’m sorry, I’m apologising now, before we work, I’m going to have to kill you. I said, well what do you mean? Nobody’s ever told me that before. And he said well, it’s not my fault, it’s just the way we’re trained in flamenco - if there’s anybody on stage with you you have to kill them. And then you have to also kill the audience!

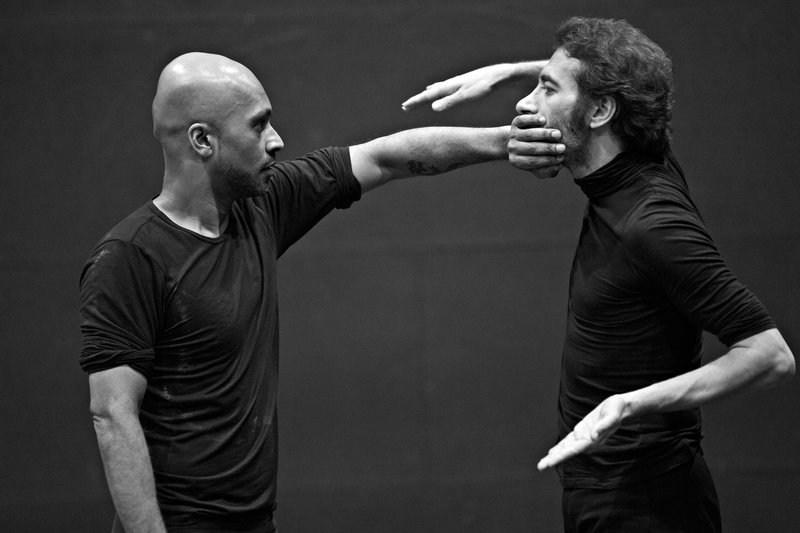

So I said, wow you’re like a mass killer and he said, well you’re like a Buddha, because everything is very spiritual for you. But what was interesting was, [that during the piece’s creation] I became the warrior and he became the Buddha, he became the monk. I would call the show Two Peaceful Warriors. He’ll tell you himself: he came [in order] to be a warrior and he ended up becoming a peaceful warrior with me. You don’t allow the audience to challenge your respect in flamenco, you just completely bombard them. You kill them before they kill you, basically. And for Kathak it’s much more sacred and much more spiritual. We try to find a more spiritual warrior within us (pictured below: Khan and Galván in rehearsal for TOROBAKA).

You certainly don't "kill" the audience yourself. In fact, your pieces often feel very tender and uplifting to watch. I had an amazing experience in the audience at Gnosis earlier this year; there was a really palpable sense of energy and connection in the stalls. Do you think the spirituality of Kathak contributes to that? Or is it just you?

It’s just me. I’m interested in emotion, I’m interested in human energy, in stories. In the end, I want the audience to feel something emotionally, not intellectually. I’ve always been drawn to Pina Bausch. I remember seeing Pina and DV8 and those were the first pieces of contemporary dance I ever saw. I had never seen contemporary before I went to university for my audition. I had a lunch break between auditions and I had to find something because I knew they were going to ask me about contemporary dance. They had VHS copies in those days [in the library], so I pulled out two videos out of maybe 100 and one of them was Pina Bausch and one of them was DV8. They both blew me away. Pina will always stay with me.

Do you remember what pieces?

The first [Bausch pieces] I saw were Café Mueller and then Rite of Spring.

I was very, very angry and I felt, why haven’t I seen this before? Why did the classical world keep me away from it? I was also shocked, especially by DV8 – I think it was [Dead Dreams of] Monochrome Men.

Do you ever go and see other dance performances nowadays?

I do, but not as much as I would like to. I miss that; I really miss seeing other people’s work. I want to see Hofesh [Shechter]’s Sun, and he wants to come and see my piece. Hofesh and I talk on the phone a lot because we both have kids now - he’s got two and I’m having a second one - and we have really nice relationship, but to get to see the work is really difficult.

If I do get out, usually I go and watch theatre. Actually I went to watch Electra last night at the Old Vic, and that was unusual for me, because it’s a long time since I saw straight theatre. Usually I go to see Théâtre de Complicité or Ariane Mnouchkine [Théâtre du Soleil], much more experimental theatre, so to watch straight theatre was quite nostalgic for me because that’s the world that I came from as a child.

I can see you doing Greek tragedy actually – have you ever been tempted to direct a play?

It’s funny you should say that. I really want to do that; I’ve already been talking about it. I really, really want to tackle a play.

Have you got one in mind?

No, but I definitely want to work with actors and dancers; I’ve been wanting to do it for ages actually. A duet I would like to do is with Simon McBurney, the director of Théâtre de Complicité. He comes from the school of thought of [Jacques] Lecoq so it’s very physical what he does.

We’ve talked about [collaborating] in the past but it’s never transpired, because I was busy during DESH (pictured below right) - wondering whether I should make a duet because I was afraid to make a solo. I always end up making duets because I’m terrified of making solos! Anyway, I’ve got it out of my system now and I’ve done the solo. I’m going to finish my performance career - full performance career, I should say (I’ll do small things but not full length pieces) with one more solo with probably six to ten musicians. That will be the last piece I do as a performer.

Can you tell us any more about that? Do you know anything about it yet?

Can you tell us any more about that? Do you know anything about it yet?

No, not really. I just know it’s going to be within the Kathak form. Working with Israel inspired me for that, to deconstruct it in a certain way and I’ve been meaning to work with - dreaming of working with - Zakir Hussain, who’s this amazing genius of a tabla player, and Yo-Yo Ma, who’s this wonderful cellist, and Chris Thile who’s an amazing mandolin player. Those are a few people I would like to invite for the project. But these are just dreams!

They sound like good dreams! When will it be?

2017, and then I’ll slow down with the performing because it takes its toll. You need to have your schedule free if you really want to be a good dancer because you have to dance all the time. I want to create more, and also be a father: I want to spend more time with my kid (from January I can say kids). I get a lot of inspiration from them, so I want to be there.

We’re actually making a mini version of DESH for kids - we’ve invited Sue Buckmaster to direct. I’m not performing - I haven’t got the time - but I’m really excited about that.

I guess that magical feel, the animation, makes it a good choice to adapt for children.

When we made it together, the collaborators and I, we really felt that it had to be a kind of Alice in Wonderland, a kind of fantasy.

DESH will be performed for the last time, for this year anyway (it might come back to London), in Manchester at the Lowry. I’ve been invited to curate an exhibition there and I’m so exited because it’s interactive, so there are performers, and we’ve brought in Anish Kapoor's work, Anthony Gormley's work, Darvish Fakhr’s work (who painted me for the National Portrait Gallery). People walk around [the exhibition] but they’ll also be guided by children and people hanging upside down. It’s a bit surreal.

What are you going to do after you stop performing? Would you think of doing what the Ballet Boyz (Michael Nunn and Billy Trevitt) did and starting your own company of younger dancers?

No. I think they’re brilliant at it, but it’s not something for me. I like to work with young people but very specifically, on specific projects. I want to work with all ages really, not just young people. I’d love to work more with the over-50s. I’m interested in people and time, not just a specific age. In iTMOi I had this woman who’s a phenomenal actress from Théâtre du Soleil. She’s a friend of mine and she plays one of the lead characters. She’s in her 50s and she studied dance when she was young, so she had this classically south Indian dance form embedded in her. I really enjoyed working with her and I’d like to do more of that, work with different ages.

We talk a lot about young people - they are the future but we also have the past, which is connected to our future. There’s so much to be offered by older dancers as well. We sometimes forget that, and I want to mix that up a little bit.

- See Akram Khan and Israel Galván in TOROBAKA at Sadler's Wells from Monday 3 to Saturday 8 November.

- See DESH at the Lowry in Manchester on Thursday 13 and Friday 14 November. One Side to the Other, the exhibition curated by Akram Khan, is at the Lowry Gallery from Saturday 15 November 2014 to Sunday 1 February 2015.

- Akram Khan and Sylvie Guillem return to Sadler's Wells with their acclaimed 2006 piece, Sacred Monsters, Tuesday 25 to Saturday 29 November.

Add comment