London 2012 and Beyond: The Best of 2012 | reviews, news & interviews

London 2012 and Beyond: The Best of 2012

London 2012 and Beyond: The Best of 2012

That was the year that rocked: omnicultural GB carries a torch for Queen and country. Plus 1962 and all that

The Mayan calendar recently suggested it was all over. It is now, almost. 2012 was, by anyone’s lights, an annus mirabilis for culture on these shores. The world came to the United Kingdom, and the kingdom was indeed more or less united by a genuine aura of inclusion. Clumps of funding were hurled in the general direction of the Cultural Olympiad, which became known as the London 2012 Festival, and all sorts leapt aboard.

Not all of what ensued, let’s be frank, left much of an impression. The public was urged to turn up to this bonfire circus or that balloon installation or such and such an encampment of soundscapes, and duly did so. But nothing was flocked to in quite such numbers, or made such an indelible impact, as the Olympic flame. The torch, designed by competition winners Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby, spent a couple of months journeying up and down the nation: carried by hundreds, it was seen by millions and snarkily dismissed by a few as a Nazi invention. This was public art at its least intellectual and most endorphin-releasing, and it fostered a mood of gathering elation and wonder. So too did Martin Creed’s nationwide bell-ringing installation on the morning the Olympic Games finally opened after seven years of clock-watching.

Not all of what ensued, let’s be frank, left much of an impression. The public was urged to turn up to this bonfire circus or that balloon installation or such and such an encampment of soundscapes, and duly did so. But nothing was flocked to in quite such numbers, or made such an indelible impact, as the Olympic flame. The torch, designed by competition winners Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby, spent a couple of months journeying up and down the nation: carried by hundreds, it was seen by millions and snarkily dismissed by a few as a Nazi invention. This was public art at its least intellectual and most endorphin-releasing, and it fostered a mood of gathering elation and wonder. So too did Martin Creed’s nationwide bell-ringing installation on the morning the Olympic Games finally opened after seven years of clock-watching.

Not all cultural celebrations clustered around the Olympics. Earlier in the year an exhibition at the National Maritime Museum celebrated the Thames as a historic waterway, while out on the river itself a thousand vessels illustrated the point. The million or so who braved the grim weather and poor sightlines were spared the BBC’s first low point of the year, in which the coverage of Pageant Master Adrian Evans’ many-splendoured flotilla was ill served by inane commentary from broadcasters who seemed not to have heard of Dunkirk. The truth is they were left high, dry and scriptless by the bosses’ decision – after the regatta had already started - to pull the short informational films which the BBC had planned to show through the three hours of river traffic. In other news, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee also produced further evidence that Cheryl Cole can’t sing and a load of old rockers have lost their voices. But then we mostly knew that.

Not all cultural celebrations clustered around the Olympics. Earlier in the year an exhibition at the National Maritime Museum celebrated the Thames as a historic waterway, while out on the river itself a thousand vessels illustrated the point. The million or so who braved the grim weather and poor sightlines were spared the BBC’s first low point of the year, in which the coverage of Pageant Master Adrian Evans’ many-splendoured flotilla was ill served by inane commentary from broadcasters who seemed not to have heard of Dunkirk. The truth is they were left high, dry and scriptless by the bosses’ decision – after the regatta had already started - to pull the short informational films which the BBC had planned to show through the three hours of river traffic. In other news, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee also produced further evidence that Cheryl Cole can’t sing and a load of old rockers have lost their voices. But then we mostly knew that.

Back to London 2012 in which, broadly speaking, there was something for everyone. My two favourite moments were rainy Celtic celebrations - because in this festival London's perimeter expanded to encompass the furthest reaches of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. On the opening night of the London 2012 Festival, I sat in a damp field on a Stirling housing estate with several thousand others listening to Sistema Scotland’s very young musicians perform the Egmont Overture with the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra (pictured above right). Rousing barely covers this emphatic advertisement for the idea that arts education turns young people into net contributors to society. Surely this more than anything was the lesson of the London 2012 Festival. (If so, it went unlearned by the Education Secretary, who announced that the arts would not form a sixth pillar to the incoming Ebacc.) Then in Ebbw Vale I had the pleasure of listening to former steelworkers reminiscing about a vanished world, sparked by Marc Rees’s spectacular Adain Avion, a giant wingless fuselage-cum-creative space which landed in the valleys for a week of steel-related events.

Back to London 2012 in which, broadly speaking, there was something for everyone. My two favourite moments were rainy Celtic celebrations - because in this festival London's perimeter expanded to encompass the furthest reaches of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. On the opening night of the London 2012 Festival, I sat in a damp field on a Stirling housing estate with several thousand others listening to Sistema Scotland’s very young musicians perform the Egmont Overture with the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra (pictured above right). Rousing barely covers this emphatic advertisement for the idea that arts education turns young people into net contributors to society. Surely this more than anything was the lesson of the London 2012 Festival. (If so, it went unlearned by the Education Secretary, who announced that the arts would not form a sixth pillar to the incoming Ebacc.) Then in Ebbw Vale I had the pleasure of listening to former steelworkers reminiscing about a vanished world, sparked by Marc Rees’s spectacular Adain Avion, a giant wingless fuselage-cum-creative space which landed in the valleys for a week of steel-related events.

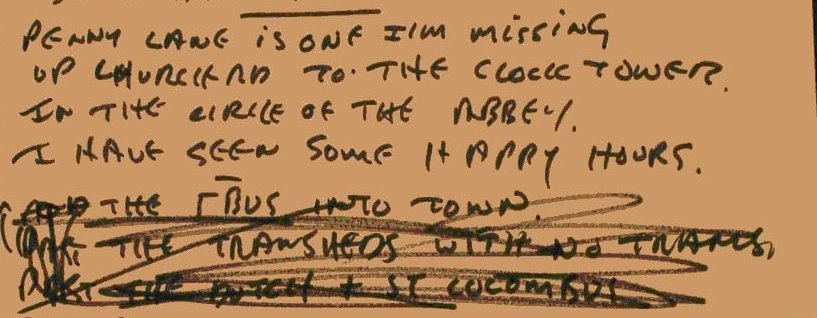

In the middle of it all, it was sometimes difficult to establish precisely what was being said. The Cultural Olympiad, from Covent Garden's epic Les Troyens downwards, often lacked the clarity of a through-line. It was in the great museums where it was possible to discern a lasting statement, a narrative palimpsest taking the measure of Britishness. The British Library’s Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands told our story in literature. (Pictured above left: John Lennon’s original draft for "In My Life" © Hunter Davies). A tour of the island as seen through its writers, you could travel from Daphne Du Maurier’s Cornwall to Dr Johnson’s Hebrides entirely through the written word, without the wearying business of trudging for miles in the wind-blasted outdoors.

In the middle of it all, it was sometimes difficult to establish precisely what was being said. The Cultural Olympiad, from Covent Garden's epic Les Troyens downwards, often lacked the clarity of a through-line. It was in the great museums where it was possible to discern a lasting statement, a narrative palimpsest taking the measure of Britishness. The British Library’s Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands told our story in literature. (Pictured above left: John Lennon’s original draft for "In My Life" © Hunter Davies). A tour of the island as seen through its writers, you could travel from Daphne Du Maurier’s Cornwall to Dr Johnson’s Hebrides entirely through the written word, without the wearying business of trudging for miles in the wind-blasted outdoors.

There was also Shakespeare: Staging the World at the British Museum, the premise of which was that, like Puck putting a girdle round the earth, the Bard somehow encompasses all creation, including Elizabethan London and the newfangled Jacobean concept of a greater Britain. (Pictured above right: Ides of March coin commemorating the assassination of Julius Caesar. Lent by Michael Winckless. Copyright of The Trustees of the British Museum). This was, for me, the exhibition of the year. It formed part of a sort of festival within a festival. For the World Shakespeare Festival, television joined in with documentaries and a season of English history plays, and the RSC did its bit, as did NTW in an aircraft hangar. As has been established in Matt Wolf’s assessment of the year onstage, these were all dwarfed by the astonishingly adventurous Globe to Globe season, which knocked spots off all other theatrical ventures.

There was also Shakespeare: Staging the World at the British Museum, the premise of which was that, like Puck putting a girdle round the earth, the Bard somehow encompasses all creation, including Elizabethan London and the newfangled Jacobean concept of a greater Britain. (Pictured above right: Ides of March coin commemorating the assassination of Julius Caesar. Lent by Michael Winckless. Copyright of The Trustees of the British Museum). This was, for me, the exhibition of the year. It formed part of a sort of festival within a festival. For the World Shakespeare Festival, television joined in with documentaries and a season of English history plays, and the RSC did its bit, as did NTW in an aircraft hangar. As has been established in Matt Wolf’s assessment of the year onstage, these were all dwarfed by the astonishingly adventurous Globe to Globe season, which knocked spots off all other theatrical ventures.

Such flavours and many more were brought out in Danny Boyle’s Opening Ceremony. Anyone who had a ticket will be crowing till the Second Coming, but for the rest of the world it had to be experienced via the minimising portal of the small screen. You saw only what the broadcast's carefully plotted story arc put before you. There were those commenting on theartsdesk’s review who had hoped for a de haut en bas lecture about British history and culture, and found fault with the craven inclusion of "Nimrod" and Mr Bean (pictured above left winning in Chariots of Fire). But for everyone else it enthralled. Kenneth Branagh, dressed as a stovepiped Brunel and channelling Caliban, embodied it all in a nutshell: somewhat to the surprise of our chums overseas who cherish the image of a sepia-tinted fantasy GB in which the natives are decent and/or cold as ice, contemporary, omnicultural Britain sits somewhere between order and chaos, genius and mayhem, grandeur and riot. Hence Twenty Twelve, a pin-sharp comedy which gave voice to our inchoate fear of mediocrity - fear, even, of ourselves. Turns out everyone got top marks.

Such flavours and many more were brought out in Danny Boyle’s Opening Ceremony. Anyone who had a ticket will be crowing till the Second Coming, but for the rest of the world it had to be experienced via the minimising portal of the small screen. You saw only what the broadcast's carefully plotted story arc put before you. There were those commenting on theartsdesk’s review who had hoped for a de haut en bas lecture about British history and culture, and found fault with the craven inclusion of "Nimrod" and Mr Bean (pictured above left winning in Chariots of Fire). But for everyone else it enthralled. Kenneth Branagh, dressed as a stovepiped Brunel and channelling Caliban, embodied it all in a nutshell: somewhat to the surprise of our chums overseas who cherish the image of a sepia-tinted fantasy GB in which the natives are decent and/or cold as ice, contemporary, omnicultural Britain sits somewhere between order and chaos, genius and mayhem, grandeur and riot. Hence Twenty Twelve, a pin-sharp comedy which gave voice to our inchoate fear of mediocrity - fear, even, of ourselves. Turns out everyone got top marks.

Finally, there were other contenders in 2012. Posterity arranged for a couple of signature Brits to have their centenaries this year. While Captain Scott may have trudged onto his plinth 100 years ago and - lest we forget - Dickens was born 200 years ago, the yesteryear that kept on cropping up was neither 1912 nor 1812. For nostalgists, 2012 was all about 1962. It was 50 years ago that not only saw the last of Marilyn Monroe but also heard the first of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, two of whom are still going strong, while Paul McCartney has become a sort of world president of pop music fated at moments of national import to roll out "Hey Jude" or "Let It Be" in a neverending loop. It's not a bad legacy for a calendar year. Time will tell whether those who follow will feel as strongly about the year which ends when, all too soon, the iron tongue of midnight tolls twelve.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment