Wordsworth would not be happy. The bard of Grasmere once wrote a poem deploring the new-fangled habit of tourists wandering about the lakes with a book in hand. “A practice very common,” he harrumphed, before crossing out the whole poem. The preference, as he saw it, should be to engage directly with the landscape rather have one’s responses fed to us through the prism of literature. Writing Britain goes one better (or worse): a tour of the whole island and its islands as seen through its writers, you can travel from Daphne Du Maurier’s Cornwall to Dr Johnson’s Hebrides entirely through the written word, without the wearying business of trudging for miles in the wind-blasted outdoors.

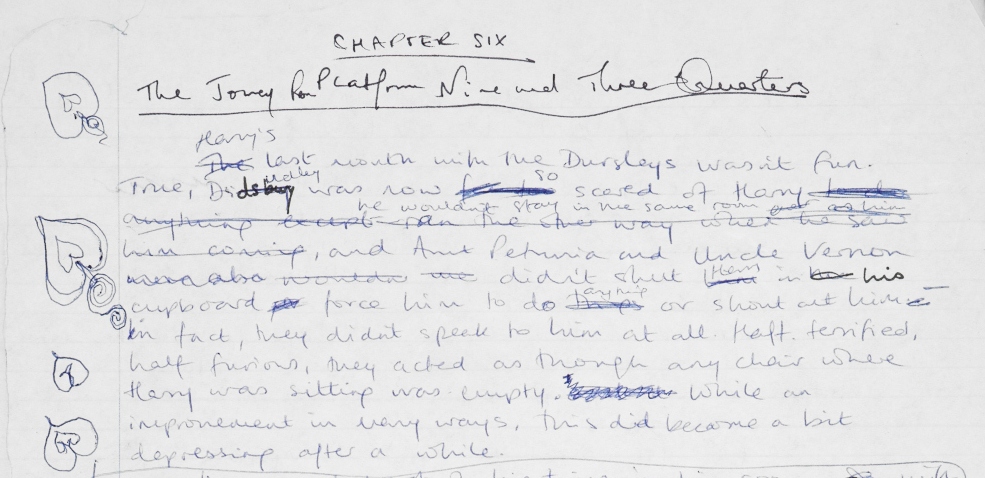

This is the exhibition with which the British Library, anticipating a summer rush of international visitors, is putting our literary heritage on show. The span is vast in every respect – in centuries covered, in literary merit and something as basic as quality of paper. From a priceless 10th-century manuscript of The Seafarer to a sheet of lined A4 on which JK Rowling scribbled a page of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (pictured above), there is something here for everyone

This is the exhibition with which the British Library, anticipating a summer rush of international visitors, is putting our literary heritage on show. The span is vast in every respect – in centuries covered, in literary merit and something as basic as quality of paper. From a priceless 10th-century manuscript of The Seafarer to a sheet of lined A4 on which JK Rowling scribbled a page of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (pictured above), there is something here for everyone

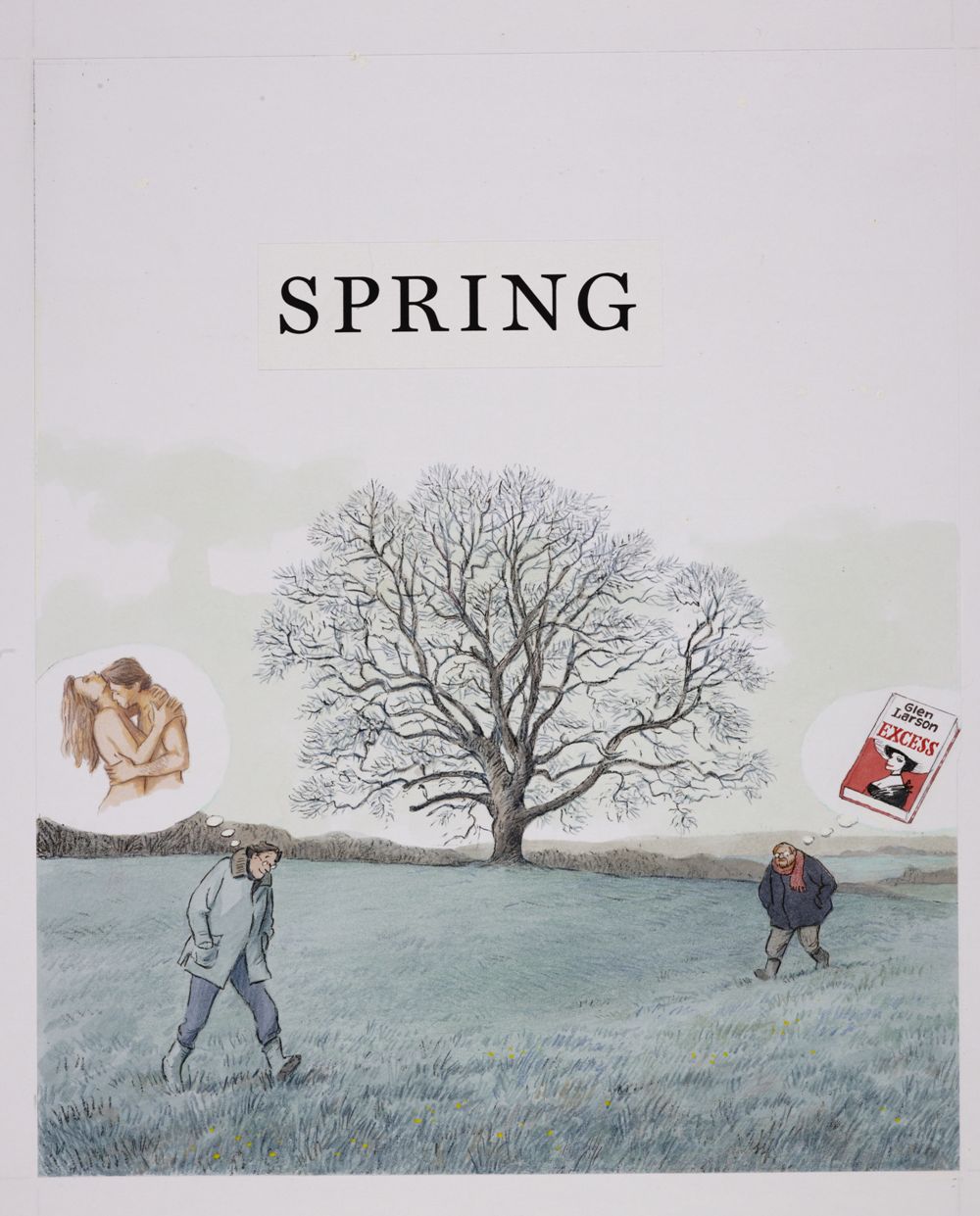

One of the show’s captivating arguments is that our national literature is a thousand-year story in a constant state of self-quotation. Wales’ compendium of tales The Mabinogion resurfaces in Alan Garner’s The Owl Service. Jane Austen’s Persuasion is followed onto the Cobb in Lyme Regis by Harold Pinter, tersely adapting The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Fay Godwin snaps the moody moorland ruin thought to have been Emily Brontë’s inspiration for Heathcliff’s lair. Posy Simmonds’ Tamara Drewe (pictured below) reboots Thomas Hardy.

Subtitled From Wastelands to Wonderlands, Writing Britain breaks up the canon into half a dozen distinct sections. We begin in the rural fastnesses of Robin Hood and the pagan Green Man where a general air of contentment and wonder is exuded by the likes of Katherine Phillip’s A Country-Life (1650), by the pastoral elegists and eulogists Gray and Clare, by Housman’s diary entry for 15 May 1891: “Oaks green... hail nearly as big as cherries.” Voicing Gwendolen Fairfax, Wilde’s looping hand gently pokes fun at the tedium of rural life in the MS of The Importance of Being Earnest: “I cannot understand how [the word 'people' is crossed out] anybody manages to exist in the country.”

Subtitled From Wastelands to Wonderlands, Writing Britain breaks up the canon into half a dozen distinct sections. We begin in the rural fastnesses of Robin Hood and the pagan Green Man where a general air of contentment and wonder is exuded by the likes of Katherine Phillip’s A Country-Life (1650), by the pastoral elegists and eulogists Gray and Clare, by Housman’s diary entry for 15 May 1891: “Oaks green... hail nearly as big as cherries.” Voicing Gwendolen Fairfax, Wilde’s looping hand gently pokes fun at the tedium of rural life in the MS of The Importance of Being Earnest: “I cannot understand how [the word 'people' is crossed out] anybody manages to exist in the country.”

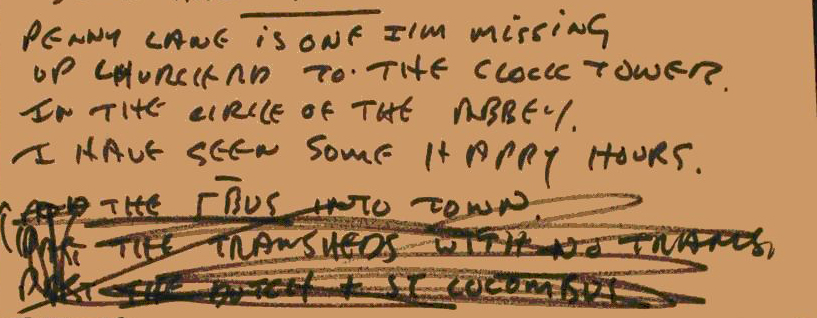

For much of our literature, all too easily. How they managed to exist in industrialised England is more moot. A letter from Charlotte Brontë in 1848 frets at “our northern congregations of smoke-dark houses clustered round their soot-vomiting mills". Elizabeth Gaskell is similarly anxious that Manchester “is not the most healthy place”. But industry is a source of fascination and even sentiment to others. Remembering the environs of childhood, Auden neatly if oddly lists Derbyshire lead mines and mining terms in a notebook from just after the war. John Lennon’s original lyrics in upper case for “In My Life” (pictured below) summon images from the Liverpool of his youth, including Penny Lane, which was eventually memorialised in song by Paul McCartney. Poignantly, “In the pram I had some good times” never made it onto Rubber Soul.

As distinct from agricultural Britain, the exhibition migrates to the unpopulated Celtic wildernesses discovered, principally, in the 18th century on England’s doorstep when the Napoleonic wars put a stop to the Grand Tour. We find Keats rhapsodising in a letter to his brother Tom about Ailsa Craig and Wordsworth at Tintern Abbey, before a tour of suburbia drags the exhibition into the early 20th century with Betjeman hymning the suburban gateway in “Baker Street Station” and Evelyn Waugh gently twitting “fair Penge”. We then head into London, the mythic phantasmagoria peopled by Chaucer, Blake and Dickens, and thence out onto the rivers, waterways and seascapes captured nostalgically by Larkin, who in neat pencil summons the sound of “the small hushed waves’ repeated fresh collapse”.

As distinct from agricultural Britain, the exhibition migrates to the unpopulated Celtic wildernesses discovered, principally, in the 18th century on England’s doorstep when the Napoleonic wars put a stop to the Grand Tour. We find Keats rhapsodising in a letter to his brother Tom about Ailsa Craig and Wordsworth at Tintern Abbey, before a tour of suburbia drags the exhibition into the early 20th century with Betjeman hymning the suburban gateway in “Baker Street Station” and Evelyn Waugh gently twitting “fair Penge”. We then head into London, the mythic phantasmagoria peopled by Chaucer, Blake and Dickens, and thence out onto the rivers, waterways and seascapes captured nostalgically by Larkin, who in neat pencil summons the sound of “the small hushed waves’ repeated fresh collapse”.

It’s a gripping national narrative, through which every visitor can be guided - as any reader would be - by their own literary tastes. Whichever way you slice it, not every exhibit can be classed as riveting. The many hardbacks on display offer a dash of colour but not a lot else. To vary the visual palette, and demonstrate that authors now and then think in actual pictures, writers supply their own illustrations. Orwell maps out a Wigan coal mine with little stickmen wielding huge shovels. Conan Doyle draws up a floor plan for his dream home in Hindhead. Galsworthy compiles a huge Forstye family tree going back to 1741. Keith Waterhouse supplies a (slightly humdrum) diagram of the fictional Chapel Langtry for his novel Jubb.

It’s a gripping national narrative, through which every visitor can be guided - as any reader would be - by their own literary tastes. Whichever way you slice it, not every exhibit can be classed as riveting. The many hardbacks on display offer a dash of colour but not a lot else. To vary the visual palette, and demonstrate that authors now and then think in actual pictures, writers supply their own illustrations. Orwell maps out a Wigan coal mine with little stickmen wielding huge shovels. Conan Doyle draws up a floor plan for his dream home in Hindhead. Galsworthy compiles a huge Forstye family tree going back to 1741. Keith Waterhouse supplies a (slightly humdrum) diagram of the fictional Chapel Langtry for his novel Jubb.

But in the larger family tree that is British literature, it’s the manuscripts which really intrigue. Beyond the persuasive argument curating them into shape, the thrill of looking over the shoulders of the great is visceral. It’s curious to note whose handwriting will have been a cinch for the typesetters to decipher (C Brontë, Wilde, A Bennett, Conan Doyle, Greene, Blake’s “Tyger, Tyger” jotted in a notebook), and whose won’t (the Our Mutual Friend MS may as well be in hieroglyphs). Interestingly, Ted Hughes’s letters are perfectly legible, his poetry much unrulier. (Pictured above: Jane Eyre, left, and Our Mutual Friend, right)

Nor can all the literature here make claims for greatness. It’s a handsome volume but posterity has turned a blind eye to Michael Drayton’s 15,000-line rural epic from 1622, The Poly-Olbion (pictured right). “Through a Triumphant Arch, see Albion plac’d,” it begins. No thanks. And sometimes the writers seem to know failure themselves. Of the many intriguing elisions and edits, the angriest is the thicket of black scratches Joseph Conrad has put through the stage version of The Secret Agent. A page of Ulysses in Joyce's hand mostly consists of red lines – it’s not clear whose.

Nor can all the literature here make claims for greatness. It’s a handsome volume but posterity has turned a blind eye to Michael Drayton’s 15,000-line rural epic from 1622, The Poly-Olbion (pictured right). “Through a Triumphant Arch, see Albion plac’d,” it begins. No thanks. And sometimes the writers seem to know failure themselves. Of the many intriguing elisions and edits, the angriest is the thicket of black scratches Joseph Conrad has put through the stage version of The Secret Agent. A page of Ulysses in Joyce's hand mostly consists of red lines – it’s not clear whose.

The aquatic finale – Spenser’s “sweete Thames”, the kept Tess contemplating murder in “the fashionable watering-place” Sandbourne/Bournemouth – is a fitting way for the exhibition to close. There is more than one watery end here: in the Mill on the Floss MS we witness George Eliot drowning the Tullivers before our eyes. John Stow’s splendid The Survey of London (1598) happens to be open on a page in which “sixe pretty young Lads, going to sport themselves upon the frozen Ducking-pond, neere Clearkenwell, the Ice too weak to support them, fell into the water”. Never to emerge.

So it's not quite true that the good end happily, the bad unhappily and that's what fiction means. But who could resist the final page of the Cold Comfort Farm MS in which Stella Gibbons wraps things up with breezy optimism? “Tomorrow would be a beautiful day. THE END.” The story continues.

- Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands at the British Library until 25 September

- More images on theartsdesk's Facebook page

Image credits:

- Chapter six, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone © J K Rowling

- "Spring", Tamara Drewe © Posy Simmonds

- John Lennon’s original draft for "In My Life" © Hunter Davies

- Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre © British Library Board

- Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend © The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York (Photography, Graham S. Haber, 2012)

- Michael Drayton, Poly-Olbion © British Library Board

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment