The soundtrack to Tate Britain’s seminal exhibition Women in Revolt! is a prolonged scream. On film, Gina Birch of the punk band The Raincoats gives vent to her pent-up anger and frustration by yelling at the top of her lungs for 3 minutes (main picture). And in many ways, this whole exhibition is a scream of rage.

Sick of being marginalised by the male-dominated art world and tired of being treated as second class citizens in every other walk of life, in the 1970s women artists went on the offensive. They began organising, protesting and demonstrating and making work that is, in itself, a form of activism.

Eschewing the star system which valorised individual male “genius” and excluded women, many worked collectively and anonymously. And rejecting traditional media such as paint on canvas, they chose alternatives such as photography, film, collage, graphics and performance, or craft materials associated with women’s work, because they came with less cultural baggage and were low status.

For instance, Su Richardson and Kate Walker began sending each other small scale artworks that fitted into an envelope; others soon joined in and the movement grew until, in 1977, the ICA was able to stage a Postal Art Event.

For instance, Su Richardson and Kate Walker began sending each other small scale artworks that fitted into an envelope; others soon joined in and the movement grew until, in 1977, the ICA was able to stage a Postal Art Event.

In 1973 Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt and Mary Kelly embarked on Women and Work, an analysis of the daily lives of women working at a metal box factory in Bermondsey, which revealed that they did two jobs – paid shifts on the production line and unpaid housework.

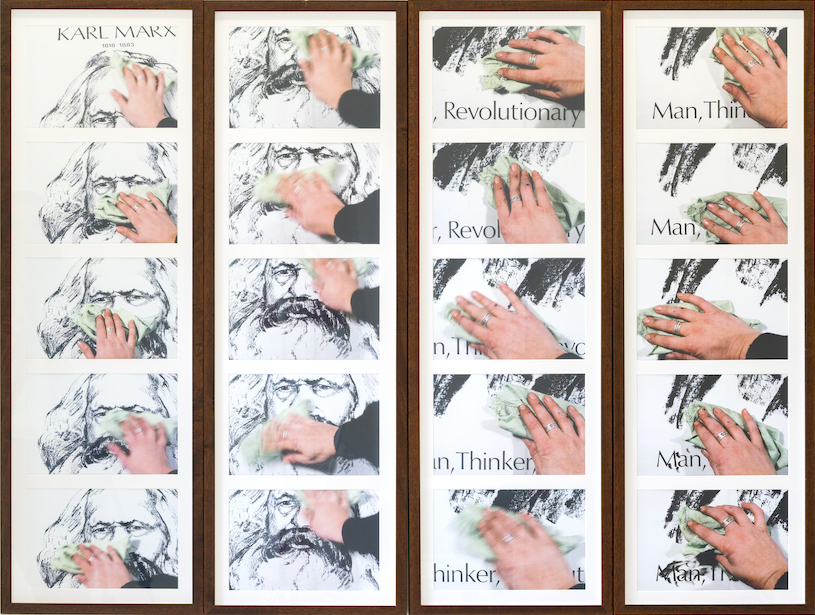

Others used ironic humour to make similar points. In Alexis Hunter’s photographic series The Marxist Wife Still Does the Housework, 1978 (pictured below left) a woman cleans a picture of Karl Marx. “Women are absent from the analysis of the labour market”, reads the caption, “and their domestic work is taken for granted.”

“Is There Life After Marriage?” asks a poster by the See Red Women’s Workshop, who began working together in 1974. It shows a disillusioned bride doing the washing up; on the photo is printed “Y B A wife?”. And their banner-like 7 Demands shows women holding placards demanding things such as equal pay and 24 hour child care.

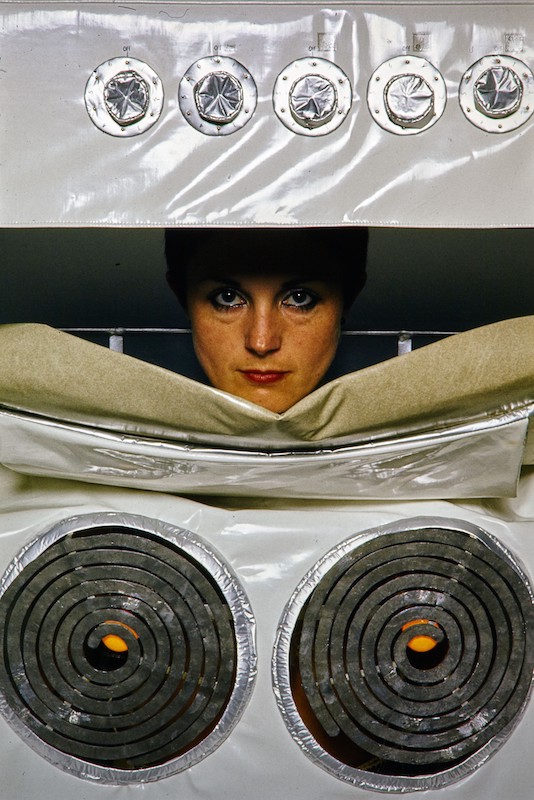

In the Kitchen,1977, was a witty performance by Helen Chadwick (pictured above right) that took the piss out of ads for domestic appliances. Wearing sculptures resembling a cooker, washing machine, fridge and sink the domestic goddess demonstrates her delight in the appliances that trap her into servitude.

I could go on. The examples are many, wonderful and various; and they only form the beginning of a large-scale survey for which the curators should be justly proud. The result of their incredibly thorough work is an extremely important and very engaging exhibition that is also overwhelming. Because it covers demos, meetings and protests like Greenham Common, and includes documentary films and photographs as well as artworks, there is too much to take in at one go. The solution is either a coffee break (I hope they allow re-entry) or multiple visits.

I could go on. The examples are many, wonderful and various; and they only form the beginning of a large-scale survey for which the curators should be justly proud. The result of their incredibly thorough work is an extremely important and very engaging exhibition that is also overwhelming. Because it covers demos, meetings and protests like Greenham Common, and includes documentary films and photographs as well as artworks, there is too much to take in at one go. The solution is either a coffee break (I hope they allow re-entry) or multiple visits.

The most striking aspect of the first rooms is how shockingly relevant the issues still are today. Hitting the news this very week, for instance, is the problem of women having to give up work because they can’t afford child care. Equal pay and equal opportunities are often nice ideas rather than realities, ads are still sexist and, if anything, rape and sexual violence are on the increase.

Work instigated by social injustice and infused with a high level of fury could be a dreary, anger filled rant if it were not for the humour often underscoring the rage and the visual fireworks with which the message is delivered.

Given their loathing of the individualism fuelling the art market, it seems invidious to single out a few works, but I can think of no other way of approaching this impressive behemoth.

Given their loathing of the individualism fuelling the art market, it seems invidious to single out a few works, but I can think of no other way of approaching this impressive behemoth.

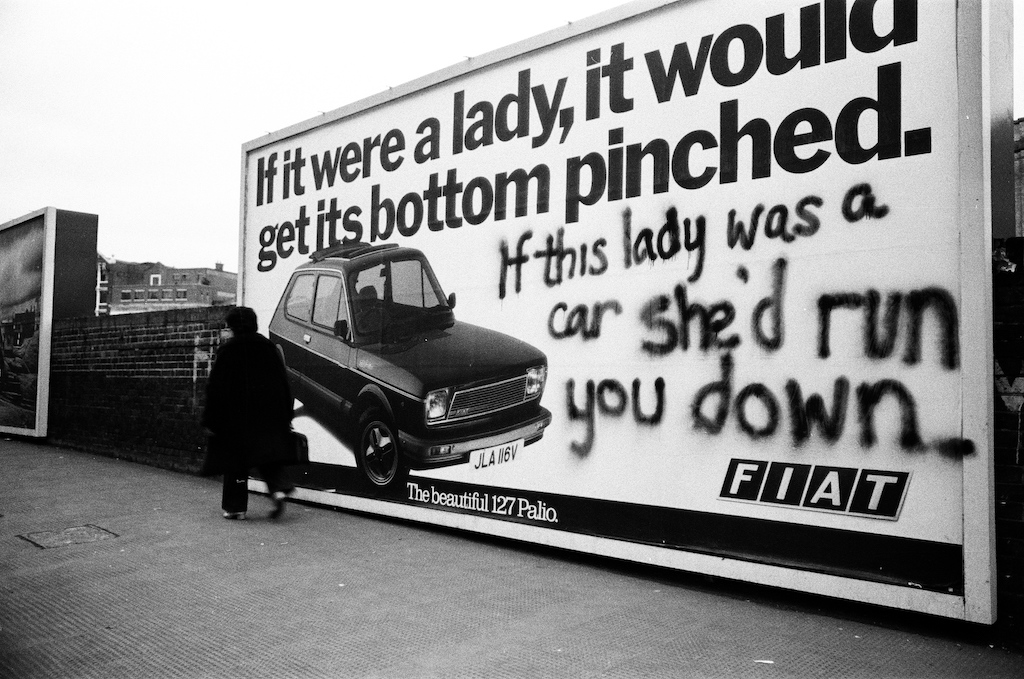

Jill Posener’s response to sexist ads was to deface them with witty graffiti, which she probably thought of as protest rather than art. Onto a Pretty Polly ad for tights that make your legs feel “as soft and smooth as the day you were born”, she scrawled “Born Kicking” and onto a Fiat ad for a car that “if it were a lady it would get its bottom pinched”, she sprayed “If this lady was a car she’d run you down” (pictured above).

To protest against the porn films shown at the Hacienda Club in Manchester where her band Ludus was playing, Linder performed in a dress made of cuts of meat. And the sleeve she designed for the Buzzcocks’ 1977 album Orgasm Addict features a woman with an iron for a head and smiling mouths with bared teeth for nipples.

As art students we were led to believe you couldn’t be an artist and a mother; and as an aspiring artist, admitting to having children was tantamount to artistic suicide. To make pregnancy the subject of your work therefore, was incredibly brave. In Susan Hiller’s Ten Months, 1977-79 (pictured above), photographs of her expanding belly are accompanied by observations about her pregnancy and on being a woman artist. “They like her to speak only about women’s things”, she writes in Month Three. “They like her to speak about everything only if she does not speak as a woman. As a woman she cannot speak.”

As art students we were led to believe you couldn’t be an artist and a mother; and as an aspiring artist, admitting to having children was tantamount to artistic suicide. To make pregnancy the subject of your work therefore, was incredibly brave. In Susan Hiller’s Ten Months, 1977-79 (pictured above), photographs of her expanding belly are accompanied by observations about her pregnancy and on being a woman artist. “They like her to speak only about women’s things”, she writes in Month Three. “They like her to speak about everything only if she does not speak as a woman. As a woman she cannot speak.”

Her remark is echoed several rooms later by Sonia Boyce on a self-portrait titled Rice n Peas, 1982, where she states “I’m not allowed to speak of anything beyond myself”. As a student at Leeds University, Sutapa Biswas was enraged at how racism was left out of discussions about the impact of class and gender in art history.

Her revenge was to paint the Hindu goddess Kali (pictured right) brandishing a bloody machete, holding a man’s severed head and wearing a necklace of shrunken heads. In another hand she holds a flag bearing a reproduction of Artemisia Gentileschi’s famous painting of Judith Beheading Holofernes. Biswas gave her painting the ironic title Housewives with Steak Knives, 1985.

Her revenge was to paint the Hindu goddess Kali (pictured right) brandishing a bloody machete, holding a man’s severed head and wearing a necklace of shrunken heads. In another hand she holds a flag bearing a reproduction of Artemisia Gentileschi’s famous painting of Judith Beheading Holofernes. Biswas gave her painting the ironic title Housewives with Steak Knives, 1985.

Del LaGrace Volcano photographed lesbian friends making out on Hampstead Heath in Queer Dyke Cruising, 1988. I wonder why her fabulously glamorous portraits of lesbians are not included, though. In Transforming the Suit, 1987, Rosy Martin wears the same outfit as she transitions in five easy pieces from business man to flirt and Madonna.

Titled Afterword, the last room feels rather sad. The Living Monument that Kate Walker built for herself helps explain why so few of the artists in the exhibition have become household names, despite the importance of their contribution for future generations of women. Tired of waiting for the recognition that never came, Walker created a monument to herself, the unknown artist. Made of grey felt marbled to simulate stone, a palette and brushes, a dress and ceremonial sash are placed above a white plinth in a tableau that reads as a memorial to thwarted ambition.

Living in a society that deprived her of opportunity both as a black woman and an artist, Lubaina Himid has been doubly disadvantaged. In her tableau The Carrot Piece, 1985 (pictured left), a white clown balances on a unicycle. His attempt to seduce a black woman by dangling a carrot from a pole is met with grave suspicion. “We understood how we were being patronised, cajoled and distracted”, reads the caption. “What we really needed to make a positive cultural contribution: self belief, inherited wisdom, education and love.” And in 2017 her determination and positivity were rewarded by winning the Turner Prize.

Living in a society that deprived her of opportunity both as a black woman and an artist, Lubaina Himid has been doubly disadvantaged. In her tableau The Carrot Piece, 1985 (pictured left), a white clown balances on a unicycle. His attempt to seduce a black woman by dangling a carrot from a pole is met with grave suspicion. “We understood how we were being patronised, cajoled and distracted”, reads the caption. “What we really needed to make a positive cultural contribution: self belief, inherited wisdom, education and love.” And in 2017 her determination and positivity were rewarded by winning the Turner Prize.

Outside on the south lawn, Bobby Baker employs another approach. Instead of rejecting the role of domestic slave, why not embrace it by transforming baking into art? An Edible Family in a Mobile Home, (pictured below) is a recreation of a 1976 installation in which she turned her East London prefab into an artwork by lining the walls and floor with newspaper decorated with icing sugar. Playing the perfect hostess, Baker offered visitors tea and cake while the other family members slouched lazily about.

At Tate Britain, students from Chelsea College of Arts will invite you to meet the family – father watching tellie, son wallowing in the bath, baby sleeping in its cot and daughter hovering weightlessly over her bed. All are made of cake, biscuits or meringue and visitors are invited to devour this idle bunch. When the cake runs out, the perfect hostess – a pink mannequin with a teapot head – will continue to dispense snacks from shelves in her chest and belly.

A lot of the work on show does not aspire to being “great art”, yet this is probably the most important exhibition you’ll see for a very long time. Relish the irony of vehemently anti-establishment work being shown at Tate Britain, an institution that many of these artists saw as the enemy and, in the unlikely event of being asked, would probably have refused to exhibit there!

A lot of the work on show does not aspire to being “great art”, yet this is probably the most important exhibition you’ll see for a very long time. Relish the irony of vehemently anti-establishment work being shown at Tate Britain, an institution that many of these artists saw as the enemy and, in the unlikely event of being asked, would probably have refused to exhibit there!

- Women in Revolt: Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990 is at Tate Britain until April 7th

- Bobby Baker's An Edible Family in a Mobile Home is on the south lawn until December 3rd, then from March 8th - April 7th 2024

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment