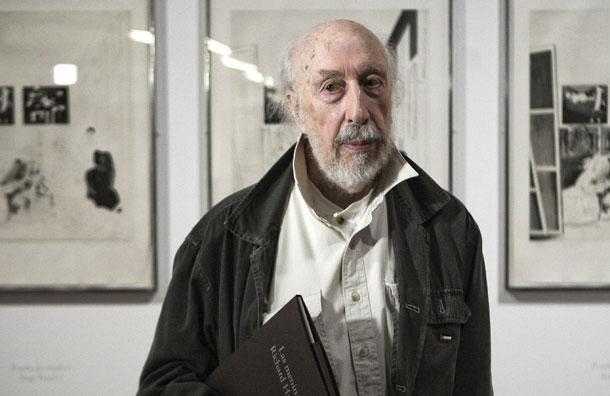

Hard on the heels of the death of Lucian Freud comes the departure of another British art great, an artist who was Freud’s exact contemporary but who seems to belong in a different aesthetic universe – Richard Hamilton. While he was the more influential of the two, by some distance, Hamilton was never a contender for that nonsensical soubriquet "Britain’s greatest living artist". His work was too challenging, too difficult to pin down and it never told Britain anything it wanted to hear about itself.

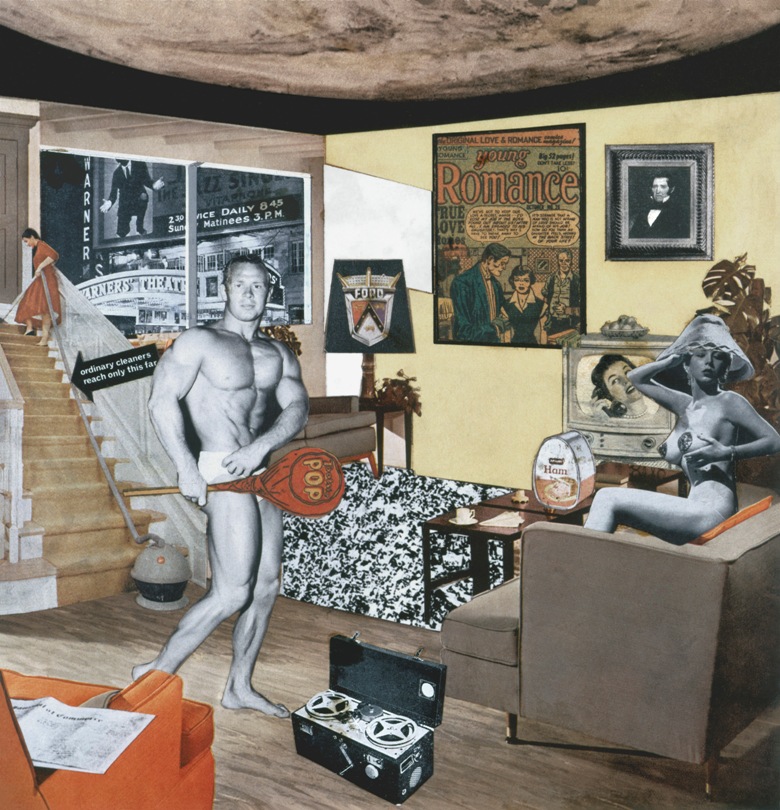

Born into a working-class London family, Hamilton left school without qualifications, becoming an apprentice in an electrical components firm and progressing to art school via evening classes. Despite this unpromising start, his work was characterised by an effortless intellectual cool, a reluctance to repeat himself or make the obvious gesture, that made him one of the most admired of British artists - but never the most loved or the most overtly imitated. His influence was far broader than that. If he was the most significant British Pop artist, effectively inventing the phenomenon with Eduardo Paolozzi in the early 1950s – and his 1956 collage Just What is it That Makes Today's Home So Different, So Appealing? (pictured right) remains one of Pop’s defining images – he had virtually given up on Pop by the time it hit the headlines in the early 1960s.

Born into a working-class London family, Hamilton left school without qualifications, becoming an apprentice in an electrical components firm and progressing to art school via evening classes. Despite this unpromising start, his work was characterised by an effortless intellectual cool, a reluctance to repeat himself or make the obvious gesture, that made him one of the most admired of British artists - but never the most loved or the most overtly imitated. His influence was far broader than that. If he was the most significant British Pop artist, effectively inventing the phenomenon with Eduardo Paolozzi in the early 1950s – and his 1956 collage Just What is it That Makes Today's Home So Different, So Appealing? (pictured right) remains one of Pop’s defining images – he had virtually given up on Pop by the time it hit the headlines in the early 1960s.

A spiritual follower of Duchamp, from the early 1950s, and later a friend and collaborator, Hamilton can be seen as the father of British Conceptualism. However, by the time Duchamp’s influence came to be universally acknowledged in the 1980s, Hamilton had been out of the picture for decades. Working with Victor Pasmore, he championed rigorous Constructivist teaching methods which were to have a decisive impact on art education in this country – though his most famous student was rock-iconoclast-turned-country-house-lounge-lizard Bryan Ferry. And while his sometime protégé Peter Blake added to his stock of public affection with his Sgt Pepper's... cover, Hamilton’s inscrutable packaging for the follow-up, The White Album – a gatefold of shiny white card – did nothing to ingratiate itself on the record buyer. His still-lifes with turds were decried as feeble, and while his protest paintings (pictured below: The Citizen [painting of Bobby Sands], 1981-3) on British involvement in Ireland were admired for their integrity, they had little impact politically or aesthetically.

If I’m making Hamilton’s career sound like a damp squib – the story of a nearly man who never hit the mark at the right time – nothing could be further from the truth. Richard Hamilton was one of the artists who got us where we are today (and if you don’t like where that is, that’s tough). His nonchalant freedom with media and themes, his repudiation of the idea of a personal visual language, an expressive handwriting by which he could be identified, all feel very much of now. Hamilton’s language lay in his ideas – which dictated the form and appearance of the final object, be it painting, collage, printmaking or computer art, of which he was a pioneer. With his assertion that art should be “sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and big business", he might have been seen as the godfather of the YBAs if that role hadn’t been taken by Michael Craig-Martin – but then how could Craig-Martin be imagined without Hamilton, a generation earlier?

If I’m making Hamilton’s career sound like a damp squib – the story of a nearly man who never hit the mark at the right time – nothing could be further from the truth. Richard Hamilton was one of the artists who got us where we are today (and if you don’t like where that is, that’s tough). His nonchalant freedom with media and themes, his repudiation of the idea of a personal visual language, an expressive handwriting by which he could be identified, all feel very much of now. Hamilton’s language lay in his ideas – which dictated the form and appearance of the final object, be it painting, collage, printmaking or computer art, of which he was a pioneer. With his assertion that art should be “sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and big business", he might have been seen as the godfather of the YBAs if that role hadn’t been taken by Michael Craig-Martin – but then how could Craig-Martin be imagined without Hamilton, a generation earlier?

For all his work’s appearance of ruthless, cerebral modernity, Hamilton was a consummately practical artist in an old-fashioned tradition of the self-taught maker and inventor, who progressed through chance encounters with pivotal texts, such as D’Arcy Wentworth’s 1917 treatise On Growth and Form, which inspired much of his early work. Far from getting others to make his work, as has become the norm among artists, Hamilton relished engaging with technology, from his first experiments with printmaking in 1939, through designing and assembling exhibitions at the ICA in the 1950s, building computers in the 1980s, to computer-manipulated imagery in the 1990s.

As an artist and a human being, Hamilton never fell back on those great standbys of British culture, coziness and gentility. A friendly and generous man, he was never quite a central figure in the art world, by and large refusing the dead hand of the establishment, becoming a Companion of Honour, but never an RA. He preferred to remain on the sidelines, taking potshots where he could, as he did with his 2007 medal portraying Tony Blair as a reckless gunslinger. At 89, Hamilton was still a subversive – perhaps the last of his kind.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment