A chronological hang of its permanent collection instead of the once so modish thematic one, a show devoted entirely to contemporary painting, which was not at all modish until quite recently – things are definitely astir at Tate Britain. Next week, the gallery will be unveiling its new Millbank entrance, restaurant and café, as part of the final stage of its two-year refurbishment and Painting Now is, I suppose one can say, one of the shows designed to re-establish Tate Britain’s prestige and increase its footfall, since it probably still suffers something of the frumpy sister syndrome next to its sexier continental sibling, Tate Modern. And if it can’t do it with big names – no Klees, no Matisses – then it can at least put on shows designed to tell you exactly where art is at, right now.

The buildings sag and droop like a many-tiered wedding cake after a few guests have piled inThis show, as the curators are careful to point out, isn’t being presented as the definitive anything – just five artists who paint, exemplary in "their practice", and who demonstrate the diversity and range of painting. And...it’s great. It’s a really interesting show, though it does start with two painters that I can’t get too excited about: Tomma Abts, who won the Turner Prize in 2006 and who’s rarely exhibited in the UK since, and Simon Ling, a figurative painter who paints buildings that look on the verge of collapse. Then it gets a bit more chewy (in a good, thoughtful and provocative way) with Lucy Mckenzie, the darling of group shows which have a claim to some intellectual heft, Gillian Carnegie, whose austere, moody and largely monochrome paintings are supremely seductive, and Catherine Story, who wouldn’t look out of place among a line-up of English surrealists, (including Paul Nash, whom she brings to mind).

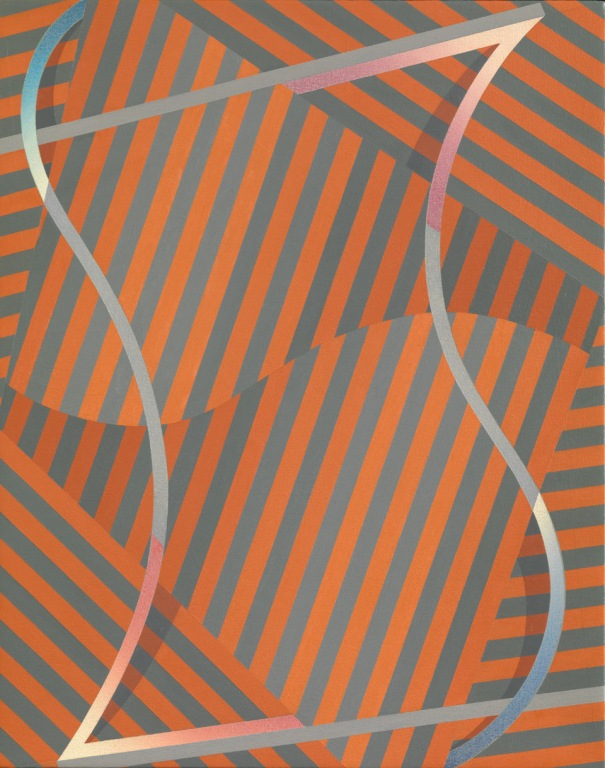

Abts is an abstract painter who paints elegant (yes, that slightly damning word) ribbons and zigg-zagging lines and intersecting and oscillating planes in gradated shades of bright colours. They’re thinly painted, with delicate, shimmering textures, and modest in size, a uniform 48cm x 38cm. And they’re given curious names, such as Zebe and Jeels and Theiel. Zebe (pictured right) is very Bridget Riley, though she tones down the vibration effect of her blue/orange diagonals with a subtle layering of darker colours. And elsewhere, too, you get that sense of “Oh, this is just like…” and then the painting slides off into altogether more elusive terrain. They have a quiet little magic going on, but, for me, they slip out of mind as easily as they delight.

Abts is an abstract painter who paints elegant (yes, that slightly damning word) ribbons and zigg-zagging lines and intersecting and oscillating planes in gradated shades of bright colours. They’re thinly painted, with delicate, shimmering textures, and modest in size, a uniform 48cm x 38cm. And they’re given curious names, such as Zebe and Jeels and Theiel. Zebe (pictured right) is very Bridget Riley, though she tones down the vibration effect of her blue/orange diagonals with a subtle layering of darker colours. And elsewhere, too, you get that sense of “Oh, this is just like…” and then the painting slides off into altogether more elusive terrain. They have a quiet little magic going on, but, for me, they slip out of mind as easily as they delight.

Simon Ling strikes one as an anomaly in this whole set-up, and not because he’s the only male artist, but because he’s a painter who taps into his inner expressionist (without ever really unleashing it), whereas restraint, rigour and meticulous precision seems to, to a greater or lesser degree, define the other four. His paintings are dirty and messy, with a creeping garishness – close-up paintings of buildings in Hackney that he’s painted en plein air, or at least they're begun that way. The buildings sag and droop like a many-tiered wedding cake after a few guests have piled in and whose carefully applied icing – that beautifully stuccoed edifice – has been scraped and nibbled round the edges. They’re all untitled, the locations withheld, though most look identifiably English and urban. (Pictured left: Untitled, 2012.)

Simon Ling strikes one as an anomaly in this whole set-up, and not because he’s the only male artist, but because he’s a painter who taps into his inner expressionist (without ever really unleashing it), whereas restraint, rigour and meticulous precision seems to, to a greater or lesser degree, define the other four. His paintings are dirty and messy, with a creeping garishness – close-up paintings of buildings in Hackney that he’s painted en plein air, or at least they're begun that way. The buildings sag and droop like a many-tiered wedding cake after a few guests have piled in and whose carefully applied icing – that beautifully stuccoed edifice – has been scraped and nibbled round the edges. They’re all untitled, the locations withheld, though most look identifiably English and urban. (Pictured left: Untitled, 2012.)

Lucy Mckenzie is the conceptualist of the group, one who uses paint, occasonally, to explore ideas that could just as neatly be expressed in other media. The paint, in other words, is arguably not really the point, although the obvious fact that they’re painted adds another element of interest and subtlety. Here she presents several trompe l’œil canvases that looks like cork boards with various items pinned on them: drawings, colour charts, photographs, reproductions of paintings. These come under the title Quodlibet, which can either mean a musical medley or a topic of philosophical discourse.

Here, with three paintings subtitled Nazism, Objectivism and Fascism (see main picture), fascism and Ayn Rand free-marketeering become interior décor tropes – you too, can get that period fascist look in your bathroom by following the design codes McKenzie carefully sets out in her little pin-board research project. It’s a witty visual deconstruction that also suggests how ideologies are, in some ways, underpinned by their surface accretions: as fashion statements, as brands, as tribal allegiances – and here as interior décor. A big, crudely painted marble-effect 3-D model Loos House, based on the interior of Adolf Loos’s house, occupies the centre of the display, and the ghost of Loos, with his modernist creed “Ornamentation and Crime” signalling a moral battlecry against superfluous decoration and "style", appears here to wag a duplicitous finger.

McKenzie would be the clear star of this exhibition were it not for Gillian Carnegie’s coolly seductive paintings in glossy monochrome: a sleek black cat on the landing of a stairwell; another, as self-contained as a sphinx, glimpsed beyond the black bars of a bannister (pictured right: Prince, 2011-12); a spiral iron stair; a vase of flowers; a tree with a swirl of abstractly spreading branches, reminiscent of Mondrian; an abstract pattern of Harlequin diamonds that provide the only burst of colour. Everything has the same value and texture in Carnegie’s paintings, but these silent and sexily impenetrable film-noirish worlds are enticing for their bold and striking geometric arrangements.

McKenzie would be the clear star of this exhibition were it not for Gillian Carnegie’s coolly seductive paintings in glossy monochrome: a sleek black cat on the landing of a stairwell; another, as self-contained as a sphinx, glimpsed beyond the black bars of a bannister (pictured right: Prince, 2011-12); a spiral iron stair; a vase of flowers; a tree with a swirl of abstractly spreading branches, reminiscent of Mondrian; an abstract pattern of Harlequin diamonds that provide the only burst of colour. Everything has the same value and texture in Carnegie’s paintings, but these silent and sexily impenetrable film-noirish worlds are enticing for their bold and striking geometric arrangements.

Finally, there’s Catherine Story and it’s difficult to make out what any of her strange figures are. The form of an ancient movie-projector in Lovelock (pictured left) seems also to suggest Mickey Mouse – with its reel-to-reel “ears” – as reconfigured by Eduardo Paolozzi. Another might be a stone carving of a toy bear, its big snout doubling as a probing lens. And two similar paintings called Big Foot are like huge flattened balloons with tiny, sad eyes. These oddly anthropomorphised objects are a bit like Rorschach tests – you see what you see. They create a mood, a sense of drama, and the drama is mysterious and sad and oddly comic.

Finally, there’s Catherine Story and it’s difficult to make out what any of her strange figures are. The form of an ancient movie-projector in Lovelock (pictured left) seems also to suggest Mickey Mouse – with its reel-to-reel “ears” – as reconfigured by Eduardo Paolozzi. Another might be a stone carving of a toy bear, its big snout doubling as a probing lens. And two similar paintings called Big Foot are like huge flattened balloons with tiny, sad eyes. These oddly anthropomorphised objects are a bit like Rorschach tests – you see what you see. They create a mood, a sense of drama, and the drama is mysterious and sad and oddly comic.

This is a very good show, but though at first it seems to demonstrate just how diverse and rich the current state of painting is, it also suggests that today’s artists – if this is in any way a true representation and I think it probably is – are keeping a tight rein on their emotions, as well their aesthetic convictions. Modernist references bob lightly back and forth, nothing fully embraced, nothing committed to. We live in the age of detachment – no, not irony, for PoMo irony long ago retired to its deathbed, but a gentler detatchment. This may be a good thing. I’m inclined for now to think it is: the mood is more serious and reflective.

- Painting Now: Five Contemporary Artists at Tate Britain until 9 February 2014

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment