Julian Schnabel: Every Angel has a Dark Side, Dairy Art Centre | reviews, news & interviews

Julian Schnabel: Every Angel has a Dark Side, Dairy Art Centre

Julian Schnabel: Every Angel has a Dark Side, Dairy Art Centre

The American painter-turned-filmmaker shows another raft of bad expressionist paintings

“Occasionally, but rarely, great imaginative leaps take place in the progression of art that seem to have come from nowhere. This can be said of Julian Schnabel….In these early paintings Schnabel worked with materials on surfaces that had never been used before....The sheer originality of Schnabel’s vision struck the art world explosively.”

So writes curator David Thorp in a catalogue essay for this exhibition. And the solemnly vacuous puff continues: “But as with all momentous changes in art these inevitably created as much criticism as acclaim.”

Let me begin by saying this. I’ve come to these paintings, painted over the course of a decade, knowing all about the praise and the opprobrium heaped on Schnabel’s earlier paintings, in the days when he was seen as the rich bad boy of the Eighties New York art scene. I’ve come to them knowing that Schnabel once compared himself to Picasso. Neither of these things matter. That is to say, they matter only in as much as they’ve bought me to this exhibition in the first place, but no more. Fame and notoriety – who said what, and for how much his paintings once sold – can only do so much of the work.

Like a lot of bad painting they all look much better in reproduction

And of course, one must be as happy to disregard the strutting utterances of artists as they are the eloquent vitriol of damning critics (one thinks of Robert Hughes’ scathing Schnabel put-downs). In the same vein, one must disregard too the hyperventilated utterances of curators such as Thorp, who, it appears, in order to correct earlier critical drubbings, have gone to bewildering extremes of praise. Since he talks of “great imaginative leaps” that change the landscape of art as we know it, should we expect Giotto, Michelangelo and Picasso rolled into one?

One would seriously think that no artist had ever used unconventional objects in a painting before (in Schnabel’s case, broken plates). All I can say is that you couldn’t pay me enough to make half the claims Thorp makes for Schnabel’s originality and genius. On show here are some very bad paintings, but if one must really claim that white is black and black is white, one would wish it to be for a better cause than Schnabel’s ego and a writer’s cheque.

There are a number of ways a work of art can be described as bad, but I'll discount what I don't mean here. I don’t mean Schnabel’s paintings are bad because of limited technical range or facility, since limited technical range and facility don't necessarily result in bad work. Nor has it much to do with disliking a kind of late postmodern aesthetic characterised by vulgarity, showiness or sentimentality, à la Jeff Koons’ porn pictures or his dopey puppies. Nor is Schnabel “bad” in that faux-naïf sense popular among painters of the Eighties and Nineties. To make a good “bad” painting you still have to be alert to many of the things that make an ordinarily good painting, not least in terms of composition and balance.

No. What I mean is that looking at Schnabel’s bad painting is simply akin to the experience of reading a bad book. A really bad book whose every sentence labours not only under the ponderous weight of its own importance but under a glut of adjectives and adverbs. You long to strip and to edit as you’re reading, to rescue the writing from its own undisciplined verbosity, its bloated yet acutely naïve sense of itself. But you have a suspicion that no amount of editing will do the job, since each sentiment is a banal generality – a hoary cliché – rather than a striking insight.

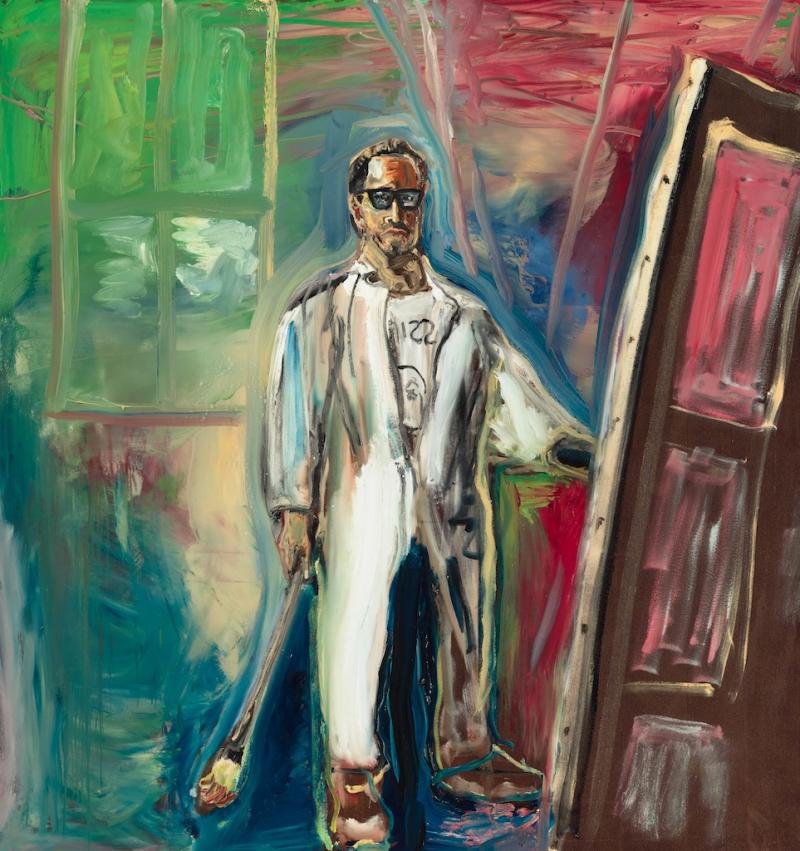

Thorp writes that “for Schnabel a painting is finished when there’s enough information in it.” Well, Schnabel certainly throws a lot into these 18 flatulent paintings, employing a variety of techniques but to little coherent effect. Some of them, the self-portraits – in one he appears in luxury pyjamas unbuttoned down to his waist (pictured right) – together with the paintings featuring an unnamed artist at his easel, remind me of Munch. Very bad Munch. Schnabel seems to want to convey some very uninteresting idea about the artist as heroic loner, confronting himself as he physically confronts and paints his own image. I look for humour as the one redeeming feature that might rescue these paintings from their overweening pomposity but humour, being a fragile thing, could clearly never survive this atmosphere of bluster. Like a lot of bad painting they all look much better in reproduction.

Thorp writes that “for Schnabel a painting is finished when there’s enough information in it.” Well, Schnabel certainly throws a lot into these 18 flatulent paintings, employing a variety of techniques but to little coherent effect. Some of them, the self-portraits – in one he appears in luxury pyjamas unbuttoned down to his waist (pictured right) – together with the paintings featuring an unnamed artist at his easel, remind me of Munch. Very bad Munch. Schnabel seems to want to convey some very uninteresting idea about the artist as heroic loner, confronting himself as he physically confronts and paints his own image. I look for humour as the one redeeming feature that might rescue these paintings from their overweening pomposity but humour, being a fragile thing, could clearly never survive this atmosphere of bluster. Like a lot of bad painting they all look much better in reproduction.

And they are big. Massive, with their opulent frames slathered in beige paint. A few have a thick layer of gloss resin, making their surfaces hard and glassy, like heavily lacquered furniture. Indeed, one thinks that Chinese dressers may have been the inspiration for this, since another series of paintings has an “oriental” theme. Images from old Zen paintings have been digitally printed on polyester, onto which Schnabel has intervened with florid expressionistic streaks and smears, writing BEZ in big graffiti letters on one, in homage to the Happy Mondays.

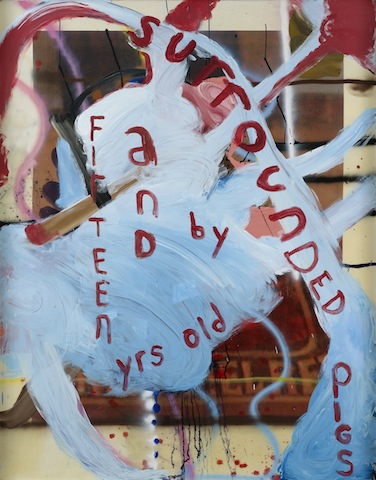

Another painting in which text appears apparently expresses his anger at the way young models are treated in the fashion industry. Fifteen Yrs Old and Surrounded By Pigs (pictured left) is an ectoplasmic explosion of dirty white paint edged with liverish pink with the words of the title floating like spaghetti letters on its surface. In fact, this is probably the only painting I like. It suggests a kind of gargantuan comic adolescent rage eating itself. Forget those other bombastic self-portraits – this is probably the only revealing one.

Another painting in which text appears apparently expresses his anger at the way young models are treated in the fashion industry. Fifteen Yrs Old and Surrounded By Pigs (pictured left) is an ectoplasmic explosion of dirty white paint edged with liverish pink with the words of the title floating like spaghetti letters on its surface. In fact, this is probably the only painting I like. It suggests a kind of gargantuan comic adolescent rage eating itself. Forget those other bombastic self-portraits – this is probably the only revealing one.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

more Visual arts

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Comments

The lead picture says it all.