It’s impossible to think about Jean Cooke’s work without taking into account her relationship with her husband, the painter John Bratby, because his controlling personality profoundly affected every aspect of her life.

Had it not been for him, she might never have become a painter at all. She studied sculpture and pottery and, when they met in 1953, was running her own pottery in Sussex. They married the same year, but Bratby didn’t want a potter for a wife, so Cooke went to the Royal College of Art to study painting.

Bratby’s  attitude was still ambivalent, though. He would only allow her to paint between the hours of 9 and 11.45 am, since there were more pressing things for her to do, such as running the house, looking after their four children, posing for him and doing his accounts. He insisted that she sign her pictures Jean Bratby because, he said, she belonged to him. Later when she began to gain recognition, though, he changed his tune, demanding that she sign herself Cooke. And despite his reservations about sharing life with a competitor, the couple exhibited together many times.

attitude was still ambivalent, though. He would only allow her to paint between the hours of 9 and 11.45 am, since there were more pressing things for her to do, such as running the house, looking after their four children, posing for him and doing his accounts. He insisted that she sign her pictures Jean Bratby because, he said, she belonged to him. Later when she began to gain recognition, though, he changed his tune, demanding that she sign herself Cooke. And despite his reservations about sharing life with a competitor, the couple exhibited together many times.

Soon after their wedding, Cooke ran away but Bratby caught up with her at the bus stop and, from then on, locked her indoors when he went out to prevent her escaping. He would also beat her up, so it’s not surprising that a friend described her as having “a prematurely haggard face from which two pale eyes gazed out fearfully”.

Those fearful eyes give her Self Portrait, 1958 an amazing intensity. Her reflection is contained in the frame of an oval mirror, within which she seems trapped. She looks terrified, as though fearful that the jailor who gave her the black eye visible in the picture might, at any moment, come bounding up the stairs behind her and catch her in the illicit act of painting.

And yet her 1962 portrait of Bratby is surprisingly sympathetic. Wearing pyjamas and a dressing gown, he slouches in a chair lost in thought. The painting is beautifully observed and highly original. Filling the canvas, the serpentine curve of his body culminates in his large bare feet, from where one’s eye tracks up his legs to the hands and head. Despite recalling that she “was thinking that he looked like Bluebeard” as she painted him, with his hunched shoulders and hands crossed over his belly, she has made him look quite harmless.

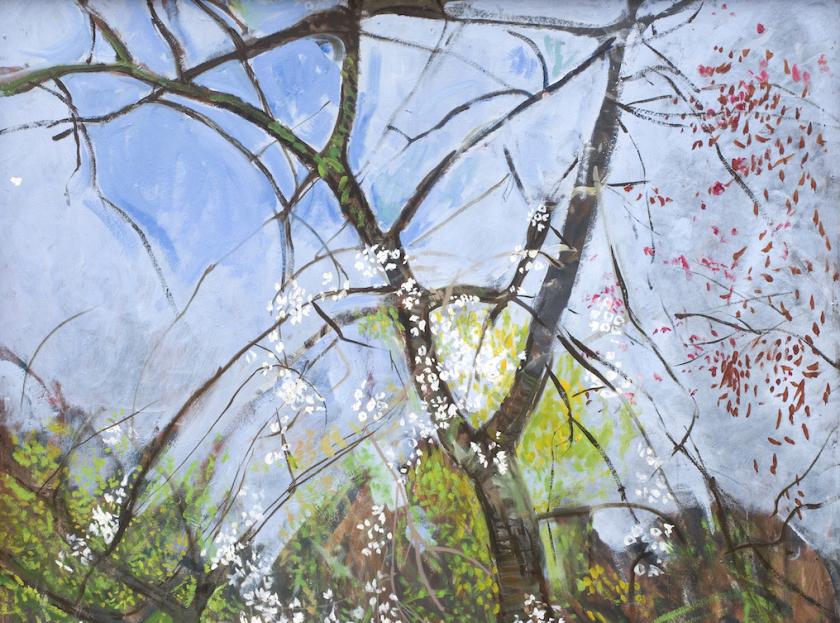

The limitations placed on her time forced Cooke to paint rapidly (pictured right: Hortus Siccus 1967) and invent ways of composing pictures from disparate sources. The couple’s house in Blackheath had a large unkempt garden, which she loved. A physical and mental escape from her domestic confinement, it became her main subject. If her self portraits are almost unbearably intense, her paintings of the garden are light and joyful in spirit. Rather like a Mondrian, the bear branches of the apple tree in Garden in Springtime 1990 (main picture: detail) are silhouetted against a blue sky, but the trunk is surrounded by a skirt of delicate white blossoms that seem to dance in airy space. While rapidly sketched over a warm brown ground, the rest of the garden seems to be bursting with life.

The limitations placed on her time forced Cooke to paint rapidly (pictured right: Hortus Siccus 1967) and invent ways of composing pictures from disparate sources. The couple’s house in Blackheath had a large unkempt garden, which she loved. A physical and mental escape from her domestic confinement, it became her main subject. If her self portraits are almost unbearably intense, her paintings of the garden are light and joyful in spirit. Rather like a Mondrian, the bear branches of the apple tree in Garden in Springtime 1990 (main picture: detail) are silhouetted against a blue sky, but the trunk is surrounded by a skirt of delicate white blossoms that seem to dance in airy space. While rapidly sketched over a warm brown ground, the rest of the garden seems to be bursting with life.

The dreamy atmosphere of Toujours en Fete, (Always on Holiday), 1969, pictured below, comes from the way the artist and her three sons are lost in their own worlds. Compiled from various sketches and memories, their meeting in this glorious garden has an almost surreal quality. Lying in his Moses basket, the infant seems to have dropped in from another dimension; Jason is absorbed in his book, while squatting in the grass, David is the only one to return the artist’s gaze. Perversely, though, Cooke can be seen at the back of the garden sitting under a pink umbrella on an invisible chair painting an invisible picture on an invisible easel, as though she too has been beamed in from another frame of reference.

Holding the separate elements together is a riot of beautifully observed flowers including daisies, nasturtiums, buttercups and cyclamen that flower at different times of the year so would never be seen together like this. Rather than describing an actual scene, then, the picture functions more like an idyll or metaphor. The holiday referred to in the title is a place in the imagination reached via the act of painting – a place to escape to where snatched moments can be brought together into a bucolic whole.

The deliciously hazy atmosphere of Pansies comes from Cooke’s habit of focusing on the main subject and leaving the rest of the picture as little more than a rapid sketch. A cluster of yellow, white and purple flowers stands on what seems to be a round table in a room delineated only by areas of thinly applied paint. The juxtaposition of keen observation and speedy brushwork sets up a conversation between figurative painting and abstraction in which each supports the other; it also anticipates Cooke’s increasingly minimalist approach. The Bratbys finally separated in the early 1970s and Cooke began visiting Birling Gap where the South Downs meet the sea and, in 1973, began renting a coastguards cottage on the clifftop. The incessant wind and salty air encouraged the sparse scattering of plants to hug the ground. The watercolours she made of her garden there show a few sprigs braving the elements against a wash of green for the sea and blue for the heavens. Exquisite evocations of big skies, wind and freedom, these delicate images strike a perfect balance between abstraction and figuration.

The Bratbys finally separated in the early 1970s and Cooke began visiting Birling Gap where the South Downs meet the sea and, in 1973, began renting a coastguards cottage on the clifftop. The incessant wind and salty air encouraged the sparse scattering of plants to hug the ground. The watercolours she made of her garden there show a few sprigs braving the elements against a wash of green for the sea and blue for the heavens. Exquisite evocations of big skies, wind and freedom, these delicate images strike a perfect balance between abstraction and figuration.

Having been elected a member of the Royal Academy in 1972 and a Senior Royal Academician in 2002, Joan Cooke enjoyed considerable success during her lifetime. But when she died in 2008, like so many women artists, she was immediately forgotten and is only now being rediscovered. The Garden Museum is to be congratulated for mounting this show, but with no natural light, this horribly cramped exhibition can’t do justice to her light and airy work.

- Jean Cooke: Ungardening at the Garden Museum until 10 September

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment