Germany / The 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Centre Pompidou review - expansive and thought-provoking | reviews, news & interviews

Germany / The 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Centre Pompidou review - expansive and thought-provoking

Germany / The 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Centre Pompidou review - expansive and thought-provoking

The vibrant world of 1920s Central Europe, in sharp focus

The businessman in Heinrich Maria Davringhausen’s Der Schieber (The Profiteer), 1920-1921 sits several floors above the city streets, pencil in hand; the high-rise buildings pressing at the windows around him. Not in Germany. In France.

Across the sixth floor of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, framed by its spectacular floor-to-ceiling windows, a sprawling, multidisciplinary exhibition is currently on show, devoted to works by the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, active in Germany in the 1920s.

In the aftermath of the First World War, avant-garde, utopian and idealistic styles were rejected as superficial by German artists who sought more realistic responses to the everyday world of post-war Germany, and to rising poverty and corruption in society. The term "Neue Sachlichkeit" was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the Mannheim Art Gallery, in 1923, to title an exhibition of paintings and designs which were neither impressionistic or expressionistic, but faithful to reality. The name was soon adopted to refer to artworks characterised by their emphasis on geometric form and unapologetic realism, but also a deep cynicism, disillusionment, and invective satire. The artistic dedication to portraying objective reality included representations of the political and economic uncertainties of the age, with urban grimness set alongside decadence; a world of inequality as much as modern liberation.

It’s the same sentiment as the heady 1939 novel of Weimar Germany, Goodbye to Berlin, by Anglo-American author Christopher Isherwood, who begins with scenes of modern metropolitan life – abounding streets, mass-produced goods, sex, glamour, frivolity, electric signage – rendered through a curiously apathetic perspective: "I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking." This is art made naughty, steely, punchy.

It’s the same sentiment as the heady 1939 novel of Weimar Germany, Goodbye to Berlin, by Anglo-American author Christopher Isherwood, who begins with scenes of modern metropolitan life – abounding streets, mass-produced goods, sex, glamour, frivolity, electric signage – rendered through a curiously apathetic perspective: "I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking." This is art made naughty, steely, punchy.

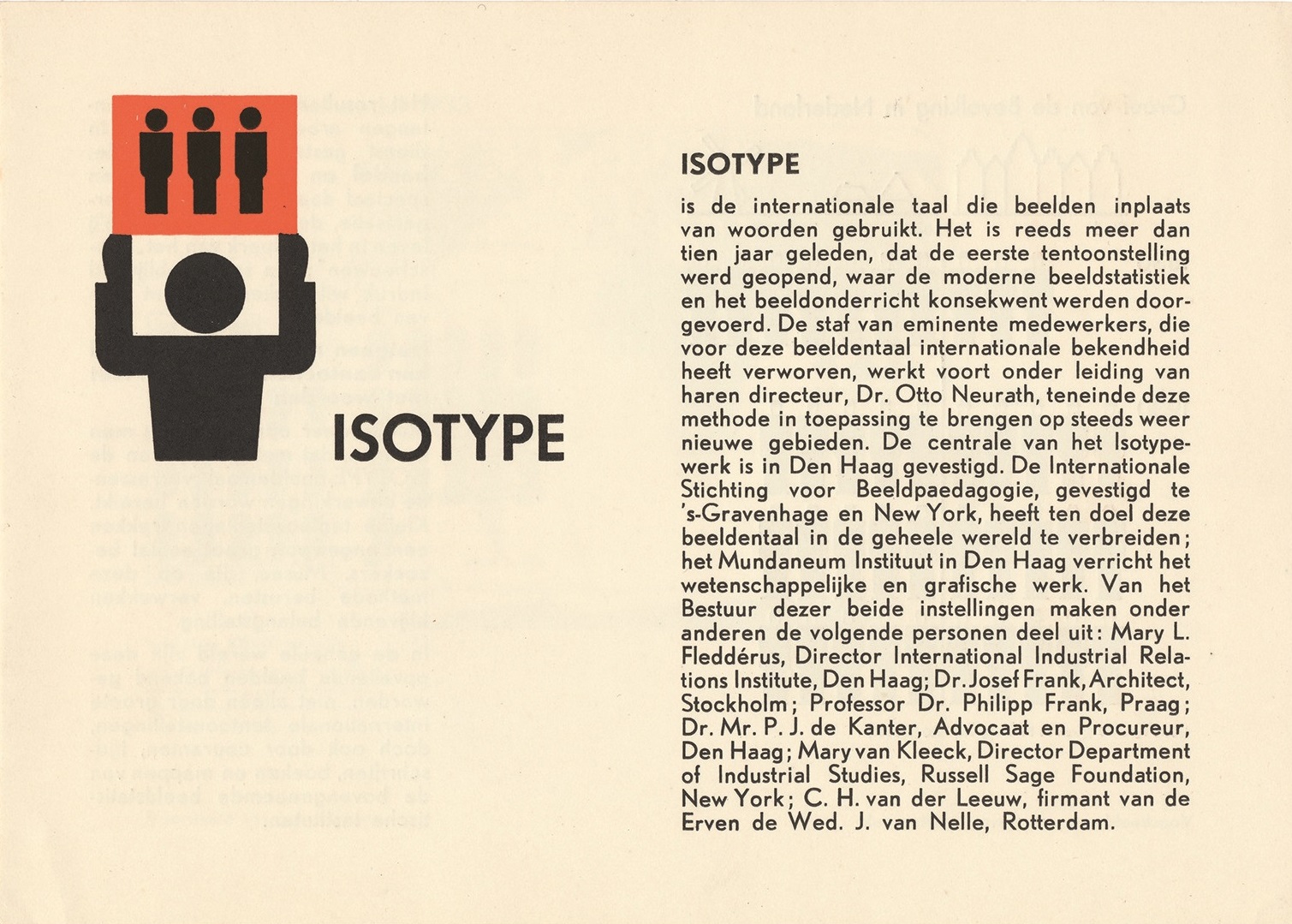

Over 900 works at the Centre Pompidou, across the visual arts, literature, film, theatre and music, trace the development of Neue Sachlichkeit from Hartlaub’s exhibition, to its sudden end following the rise of the Nazi Party. The famous faces of the movement, including Otto Dix and Georg Grosz, feature heavily – top of the bill is Dix’s 1925 portrait of German dancer and femme fatale Anita Berber, smouldering in crimson – but the exhibition also includes vast details about the subgroups and spin-offs inspired by the movement. The split of Neue Sachlichkeit into "right and left wing" variants – the former offering more timeless depictions, the latter focusing on social issues – is described in detail, with more politically-leaning works contextualised alongside other forms of artistic protest. Notable is a section on German graphic design – one wall is taken up by a 12-piece collection of engravings of Houses of the Time by Gerd Artnz, which hierarchically represent the organisation of capitalist society across different modern buildings or locations. Also included is Artnz’s later collaborations with economist Otto Neurath and designer Marie Reidemeister on pictograms, or "isotypes"; a 4000-symbol dictionary, designed to communicate statistical data on demographics, politics and economics to the wider public (pictured above).

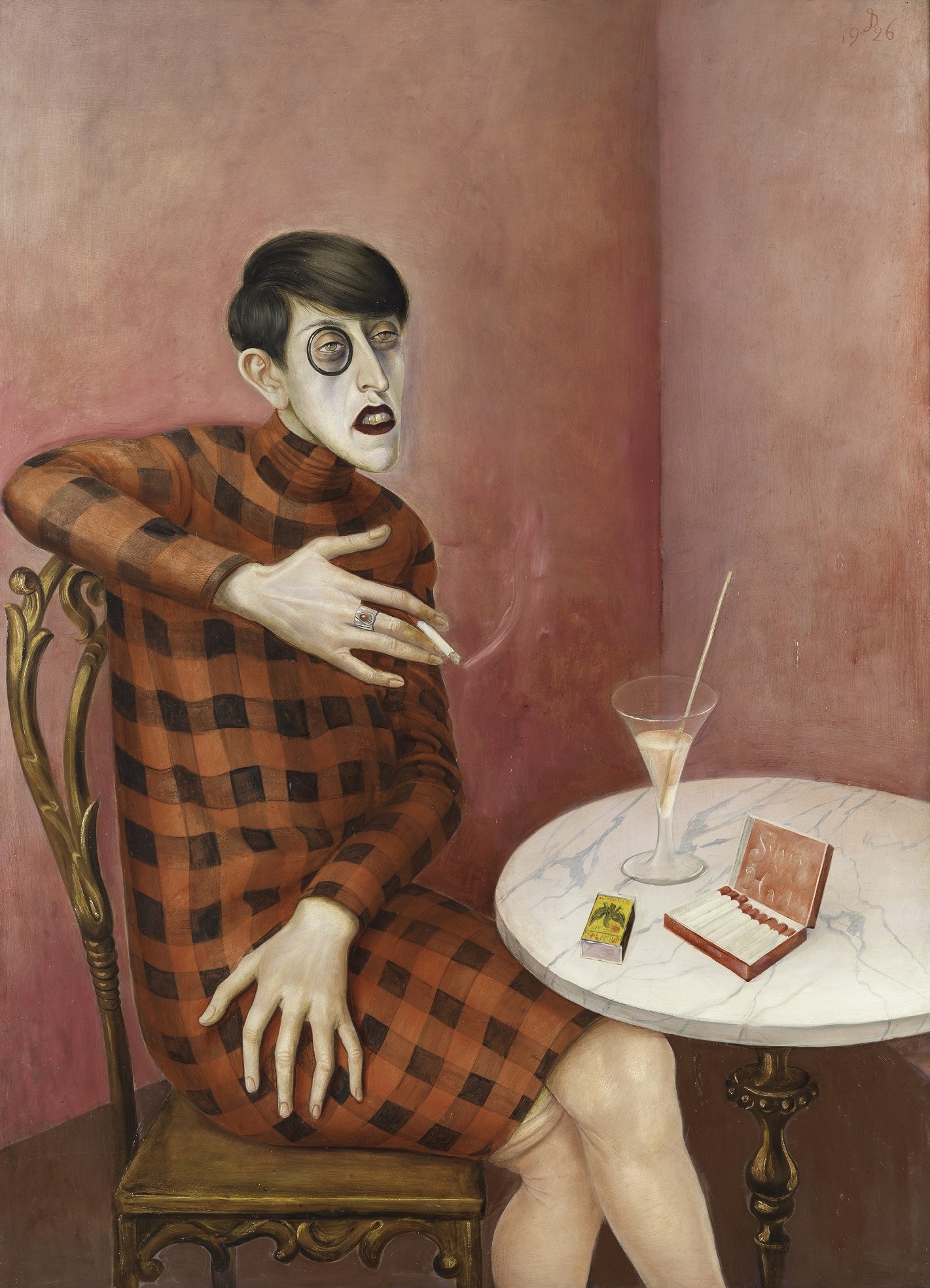

A large portion of the exhibition is dedicated to the Neue Sachlichkeit embrace of sexual exploration and the transgression of traditional gender roles. From artworks by the German-Jewish artist Gert Wollheim, including the untitled 1926 painting Couple, depicting two androgynous characters, dressed in male-coded clothing; to Jeanne Mammen’s effervescent 1928-29 depiction of dancer Valeska Gert, bow around her neck and hair cropped short, pursing her lips gleefully at the viewer; to Dix’s renowned portrait of the monocled journalist Sylvia von Harden (pictured below right), which later featured in the 1972 hit musical Cabaret – the Centre Pompidou offers a comprehensive picture of the New Women, LGBTQ+ communities and sexual freedoms of Weimar Germany. Importantly, the exhibition also includes information on the repression faced by many in Germany at the time, and after the rise of the Nazis. In the mid-1930s, artists like Mammen and Dix were denounced by Nazi authorities as "degenerate", and much of their work destroyed. Many of the artists themselves went into exile.

But the exhibition is not merely a story of German modern art, and it crucially situates Neue Sachlichkeit among broader international contexts. The influence of American business, functionalism and utility is well examined – including Bauhaus influences like the Fuld telephone, the first cradle telephone, which was designed by Marcel Breuer and Richard Schadewell in 1927-28. There is also a substantial focus on artworks from or inspired by German-speaking cultures across Europe, such as reportage (for example, Otto Umbehr’s techno-utopian photomontage of the Austrian and Czechoslovak journalist, Egon Erwin Kisch, who was known as "The Racing Reporter") and theatre, including works by the Austrian composer Ernst Křenek.

But the exhibition is not merely a story of German modern art, and it crucially situates Neue Sachlichkeit among broader international contexts. The influence of American business, functionalism and utility is well examined – including Bauhaus influences like the Fuld telephone, the first cradle telephone, which was designed by Marcel Breuer and Richard Schadewell in 1927-28. There is also a substantial focus on artworks from or inspired by German-speaking cultures across Europe, such as reportage (for example, Otto Umbehr’s techno-utopian photomontage of the Austrian and Czechoslovak journalist, Egon Erwin Kisch, who was known as "The Racing Reporter") and theatre, including works by the Austrian composer Ernst Křenek.

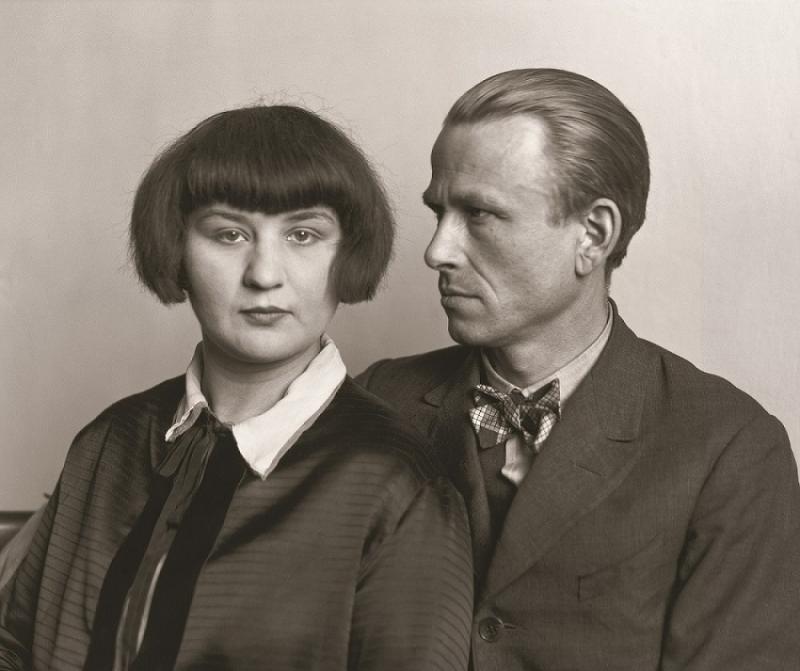

But through the heart of the floorspace is a meandering exhibition-within-an-exhibition, showing the portrait photography of August Sander, whose images of individuals from across all walks of life – who, though often left unnamed, were strictly categorised into different professions – was an attempt to capture a representative vision of contemporary German life. His first book, the 1929 Antlitz der Zeit (The Face of Our Time) contained 60 photographs from this much larger project – though it was seized and destroyed by the Nazis in 1936. During the war, Sander also photographed individuals for Eastern Europe who had been forced to work in Germany. Many of his photographs, including thousands of negatives, perished in bombing raids and fires in the war – but some survived, and his output has since been rediscovered, and his photographs now hailed as an important record of the changing face of interwar Europe in the early 20th century.

One of his most famous images – and the artwork featured at the very start of the Centre Pompidou’s exhibition – Young Farmers, shows three young friends, dapper in hats, suits and canes, and caught almost unawares, as they amble along the edge of a field towards a dance. Taken on the eve of World War One, the photograph has been variously analysed by critics, including John Berger, as evocative of the end of an era of history. But in their neat dress and careful, choreographed poses, the photograph marks the end of an era in the arts, too. New Objectivity, with its gritty and witty bleakness, was the world of the next.

- Germany / The 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander is at the Centre Pompidou until 5th September 2022

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment