The back cover of my book makes a big claim. “This book dares”, it says, “to predict the 100 most significant works of art made since the 1990s.” Although the tagline is an entirely accurate description of what I attempt to accomplish in my study of contemporary art, the phrase “dares to predict” has always made me a little anxious. It seems to suggest that the act of forecasting or foreseeing is deliberately provocative, defiant, or even risky.

The truth is, ours is The Age of Prediction. Every time we grab for our smartphones to tap out a text message to a friend, and everytime we click onto Google, an algorithm deep inside the mind of the gadget revs up to propose the next word it thinks we want to type: to predict what we really want to say. Click over to Amazon, and another sophisticated formula is invisibly limbering up, working out a list of books it believes we’d like to read next, or music tracks we’d like to hear, based on everything the formula has hoovered into itself about our tastes. Open up Netflix, and a helpful list of cinematic predictions greets you, confident it knows what kind of experience you’ll want to have as the evening unfolds.

If this kind of personalised predictiveness feels relatively new (a fresh reality only feasible because of recent technology), cultural prognostication itself is age-old and dates back at least to Bronze Age Mesopotamia and the ancient Akkadian Empire. It is to this early period of human history (24th century BC) that the making of the very first dictionaries is traceable: word lists that collect the coinages that their compilers predicted would continue to be useful. Today, it is estimated that somewhere in the world, a new word is invented every 98 minutes.

If this kind of personalised predictiveness feels relatively new (a fresh reality only feasible because of recent technology), cultural prognostication itself is age-old and dates back at least to Bronze Age Mesopotamia and the ancient Akkadian Empire. It is to this early period of human history (24th century BC) that the making of the very first dictionaries is traceable: word lists that collect the coinages that their compilers predicted would continue to be useful. Today, it is estimated that somewhere in the world, a new word is invented every 98 minutes.

However handy or helpful these neologisms may seem to those who devise them, very few new coinages will transcend the local and specialised circumstances of their minting and enter common currency among ordinary people. For every “serendipity” (created by Horace Walpole in the 18th century) that survives, a thousand “nimgimmers” (an obsolete word for a physician who treated plague victims) falls out of use. The challenge that faces compilers of dictionaries is foreseeing which words will continue to be in circulation after the pages have been printed and the glue on the spine has dried.

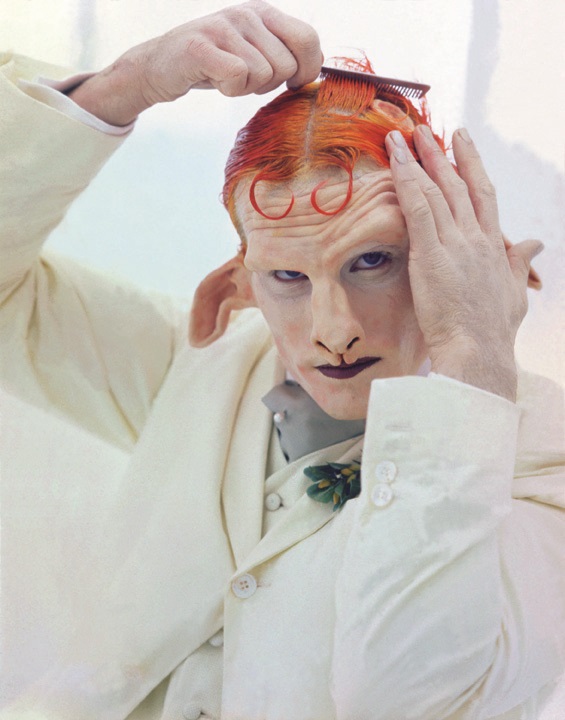

The challenge that faced me in selecting and writing about the paintings and sculptures, photographs and installations, performances and videos that comprise 100 Works of Art That Will Define Our Age was no different and, in a sense, no more recklessly audacious than that which faces the editors of the Collins Pocket Dictionary or the Concise OED. My task was to identify those works of visual art created in the last generation (or since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989: the year I selected as my starting point) that will continue to reverberate meaningfully in popular imagination a century from now. Convinced that art is among the shapes of culture for which every era is most vividly remembered, I wanted to identify those future relics from our own age that will ultimately stand for us in the eyes and minds of posterity (Pictured above right: Matthew Barney, Cremaster 4, 1994 and main picture: Cornelia Parker, Breathless, 2001).

Many of the works in the volume selected themselves. Whether you admire them or doubt the aesthetic integrity of their design, British artist Tracey Emin’s dishevelled My Bed, 1998, and Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God, 2007, indisputably shaped (and continue to shape) the conversation surrounding the art of our time like few contemporary works in art history have managed in their own eras. So indelibly have these visual coinages etched themselves into cultural consciousness, their erasure is almost inconceivable. Hirst’s skull will forever continue to symbolise egregious improvidence on the eve of global financial crisis as compellingly as Géricault’s Raft of Medusa has come to connote imperial inhumanity.

Sensation alone, however, is hardly sufficient to propel a work into the momentum of regard necessary to be remembered. The vast majority of the pieces chosen for my book have distinguished themselves on levels of technical mastery and indomitability of spirit. The sombrous eye-music of Sean Scully’s ongoing series of abstract paintings Doric, whose spare notes of monochromatic oil-on-aluminium hymn the cultural legacies of Greece at a moment when many in the global economic community have clamoured to cut that nation adrift, is among the most resonant. To stand at the epicentre of American sculptor Richard Serra’s labyrinthine Corten-steel sculpture Blind Spot, 2002-3, or to watch the endless unwinding of Christian Marclay’s cinematic masterpiece The Clock, 2010 (a 24-hour film comprised of thousands of snippets from Hollywood movies in which clocks or watches appear, spliced to keep real time with the real world) is to lose oneself in the fabric of timeless creative genius. (Pictured above right: Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010.)

Sensation alone, however, is hardly sufficient to propel a work into the momentum of regard necessary to be remembered. The vast majority of the pieces chosen for my book have distinguished themselves on levels of technical mastery and indomitability of spirit. The sombrous eye-music of Sean Scully’s ongoing series of abstract paintings Doric, whose spare notes of monochromatic oil-on-aluminium hymn the cultural legacies of Greece at a moment when many in the global economic community have clamoured to cut that nation adrift, is among the most resonant. To stand at the epicentre of American sculptor Richard Serra’s labyrinthine Corten-steel sculpture Blind Spot, 2002-3, or to watch the endless unwinding of Christian Marclay’s cinematic masterpiece The Clock, 2010 (a 24-hour film comprised of thousands of snippets from Hollywood movies in which clocks or watches appear, spliced to keep real time with the real world) is to lose oneself in the fabric of timeless creative genius. (Pictured above right: Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010.)

We live in The Age of Prediction and I foresee a time, decades from now – centuries – when a future generation will look back at us and equate who we are with the remarkable visions and artistic courage of such artists as Belgrade-born Marina Abramović, who sat for nearly 800 hours in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, staring into the eyes of an endless parade of visitors, whittling art down, one face at a time, to nothing more than an irreducible gaze. Or of Kenyan-born collagist Wangechi Mutu, who salvages from incongruous materials and a blizzard of exploitative images a brutal beauty in her portraits of African women. Are these predictions too bold? Let’s agree to meet back here in 100 years and see who’s right.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment