Nolan: Australia's Maverick Artist, BBC Four review – a lust for life in all its aspects | reviews, news & interviews

Nolan: Australia's Maverick Artist, BBC Four review – a lust for life in all its aspects

Nolan: Australia's Maverick Artist, BBC Four review – a lust for life in all its aspects

The gifted painter from Down Under who rocked the art world

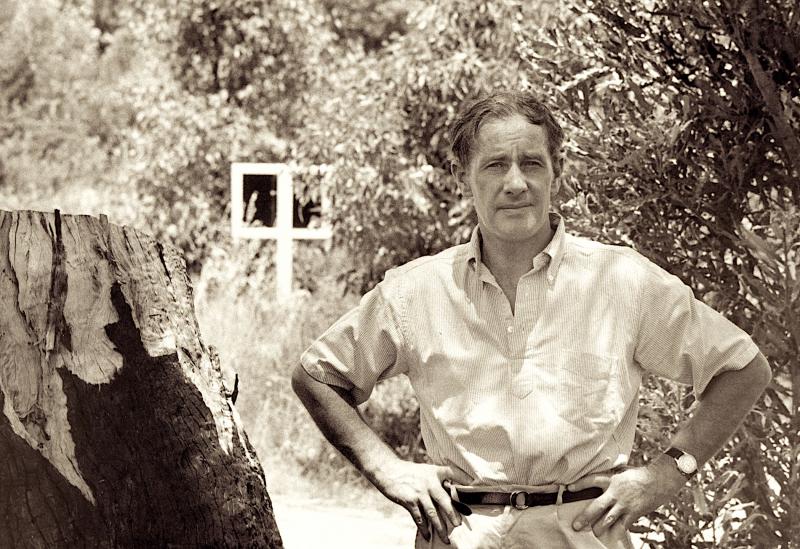

Reckless, unstoppable, one step ahead of everyone else, a hell of a lot of fun, utterly charming, street smart – descriptions of the artist Sidney Nolan (1917-1992) poured out from colleagues, rivals, curators, art historians and dealers, not to mention friends and family, in this persuasive film.

All agreed you could not compare this working-class original with anybody else. But first we heard Nolan himself eulogising gum trees, the river and the Australian sunlight, and from time to time the programme opened up to the landscapes of Oz which so moved the artist, from lush greenery to the surreal moonscapes of drought punctuated by the desiccated carcasses of sun-baked animal, victims of the extreme climate. At 14 Nolan left school and his enormous energy was turned to the arts. He was, we were told, an Artist with a capital A and painting took over his life. He eloped with Elizabeth, a young art student, and had a daughter, Alameda. All his life he insisted on his working-class roots, and had an intense love-hate relationship with the Establishment from Oz. He was based in England for his last 40 years.

At 14 Nolan left school and his enormous energy was turned to the arts. He was, we were told, an Artist with a capital A and painting took over his life. He eloped with Elizabeth, a young art student, and had a daughter, Alameda. All his life he insisted on his working-class roots, and had an intense love-hate relationship with the Establishment from Oz. He was based in England for his last 40 years.

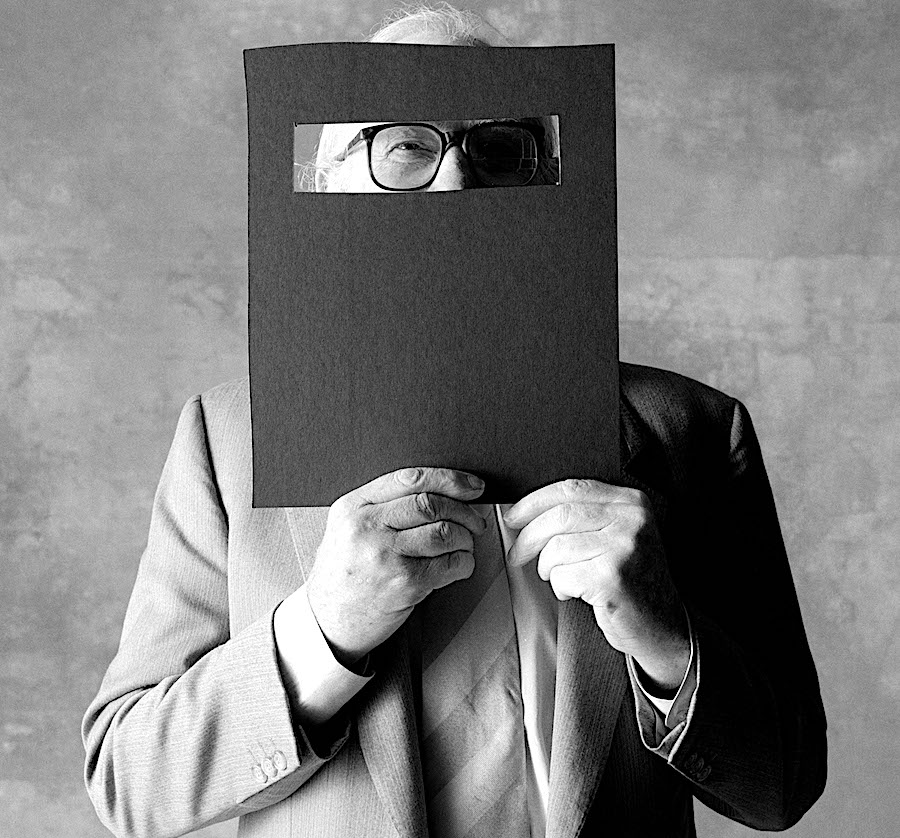

A big exhibition of modern art was brought to Melbourne in the 1930s by Keith Murdoch (the father of you-know-who) and his Herald newspaper, and at 21, Nolan was swept away; with no money to back him up, he metaphorically jumped off the cliff. Early Nolan created energetic derivative abstracts, resonant with colour, and caused a scandal: a viable plausible push for modernism in Australia, zero acceptance in Melbourne. John and Sunday Reed, defying prevailing opinion, became patrons andd offered financial support. Nolan joined the Reeds. Sidney fell for Sunday who was his aide de camp for the Ned Kelly paintings which he painted at the Reeds’ dining room table and were to make his name (Nolan does Ned Kelly, pictured above).

The imaginative scenes set in the iconic Australian landscape of the outlaw remain a huge achievement, with one fetching the highest price yet for a 20th century Australian painting – over $5m. Complications ensued with a menage à trois; then Sunday would not leave John to be with Sidney and Sidney left his own tiny family, reconnecting with his daughter years later when he and a television crew visited. You couldn’t make it up. The tiny avant-garde artistic community included Arthur Boyd, Albert Tucker and John Perceval.

Nolan’s passion for landscape was portrayed with compelling vistas of Australia’s extraordinary and idiosyncratic nature. We witnessed the pink sheen of central Australia and the aerial views that so affected Nolan, and the surreal moonscape aridity of drought-affected Queensland. The next twist and turn was the unexpected patronage of Kenneth Clark, the Lord of Civilisation himself who persuaded the young artist to come to London. Nolan married his second wife, Cynthia, John Reed’s sister. A depressive, she later committed suicide. Nolan’s third wife was Mary, Arthur Boyd’s sister. Living in London, Nolan became the first Australian artist to have a reputation outside his homeland.

He worked and networked incessantly, vintage film showing him with the great and the good, royals and all, at grand gallery openings, the decorum already charmingly dated. And he travelled incessantly – Antarctica, the Silk Road, China, Africa, all scenes for his omnivorous practice, putting human narrative into a global landscape. Nolan had a sharply focussed visual memory, referring often to his quick flicks as he explored the imagery stored in his brain. He loved new possibilities, was addicted to taking Polaroids and finally to the possibilities of the Paintbox computer programme.

He worked and networked incessantly, vintage film showing him with the great and the good, royals and all, at grand gallery openings, the decorum already charmingly dated. And he travelled incessantly – Antarctica, the Silk Road, China, Africa, all scenes for his omnivorous practice, putting human narrative into a global landscape. Nolan had a sharply focussed visual memory, referring often to his quick flicks as he explored the imagery stored in his brain. He loved new possibilities, was addicted to taking Polaroids and finally to the possibilities of the Paintbox computer programme.

He used house paint, industrial paint, spray paint, his hands and fingers as well as brushes, ever innovative. Complacency he considered the enemy: artists, he declared, were people who could think rather than people who could paint. Throughout, he had also designed for stage and theatre. London’s Royal Opera thought him a genius, and his set and costume designs for Saint-Saens’ Samson and Delilah (1981) were an innovative landmark.

This documentary was a surprisingly unpretentious and convincing portrait of an artist, persuasively showing in what particular ways Nolan evolved his own idiosyncratic and memorable language. He was motivated by his relentless curiosity and relentless imagination, no maverick he but a true original. However inexplicable the nature of inspiration, it was an informative pleasure to observe Sidney Nolan through the landscapes he saw, the observations of professionals and family, and a complex web of personal relationships. And there was the curiously elegant figure of the man himself as he wove his illuminating way through the various worlds he inhabited.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Comments

Are you sure Cynthia was

Are you sure Cynthia was Sunday sister ( or SIL ) ?

From: theartsdesk

Many thanks to those who pointed out that Cynthia was John Reed's sister, not Sunday's. Now corrected.