The Man Who Shot Beautiful Women, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

The Man Who Shot Beautiful Women, BBC Four

The Man Who Shot Beautiful Women, BBC Four

The welcome return of the legacy of photographer Erwin Blumenfeld

You can only marvel at the family intrigues that virtually closed down the legacy of photographer Erwin Blumenfeld in the years following his death in 1969.

It’s astonishing that it’s the first such screen tribute to a figure of Blumenfeld’s stature: the efforts of the second generation of his descendants have clearly done much to right first-generation squabbles. Another grandchild, Nadia Charbit Blumenfeld, has coordinated the restoration of much of the photographic legacy, now being re-assembled in a new online archive. There’s been a recent burst of exhibition activity too, the latest part of which, Blumenfeld Studio: New York, 1941-1960 (including "City Lights", pictured right) collecting around 100 works made at the photographer's 222 Central Park South workplace, opens this week at Somerset House in London.

It’s astonishing that it’s the first such screen tribute to a figure of Blumenfeld’s stature: the efforts of the second generation of his descendants have clearly done much to right first-generation squabbles. Another grandchild, Nadia Charbit Blumenfeld, has coordinated the restoration of much of the photographic legacy, now being re-assembled in a new online archive. There’s been a recent burst of exhibition activity too, the latest part of which, Blumenfeld Studio: New York, 1941-1960 (including "City Lights", pictured right) collecting around 100 works made at the photographer's 222 Central Park South workplace, opens this week at Somerset House in London.

The story could serve as an object lesson to any artist in how not to arrange their posthumous fate. When Blumenfeld died in 1969 he left management of his estate to his assistant Marina Schinz (the third love of his life, and more than 40 years his junior) with copyright divided in quarter-shares between her and Blumenfeld’s three children, the youngest of whom, Yorick, does much of the remembering in the film. Whatever it was exactly – a lack of interest at the time in vintage prints, Schinz’s decision to go ahead with her own life and not champion Blumenfeld's legacy, even simple confusion as to who had what – may not have been spelt out here in detail, but it clearly brought on a tug-of-war that wasn't short on animosity.

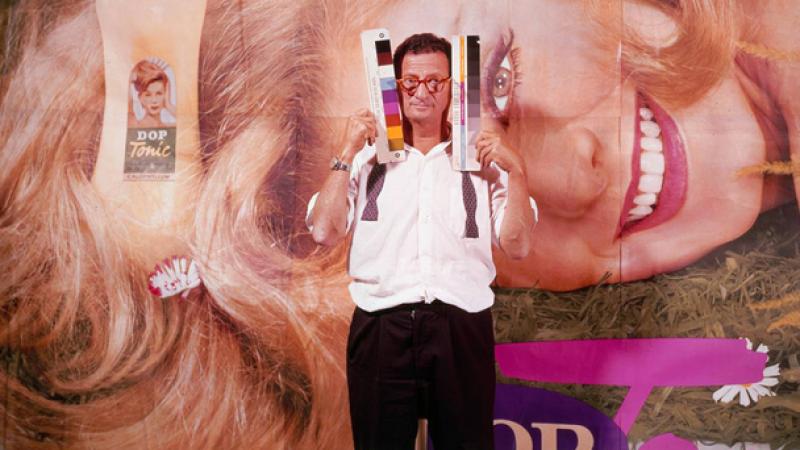

We can only raise a cheer that the heritage issue has been fixed at last. It’s hard to know what exactly to salute Blumenfeld for today, but the attention given here to his early work as a collagist in the 1920s, and association with German Dada, was long overdue. Better known is his pioneering art photography, developed in Paris after his move there in 1936 – though it never earned him a living – including multiple exposures, solarized and contrast-printed work. Cecil Beaton tracked him down in 1938, saluting him as “incapable of compromise… better than fashion”, though Beaton still introduced him to Vogue, for whom Blumenfeld would produce some of that magazine’s greatest covers ever (an example from 1950, pictured above left). Blumenfeld entered fashion properly after his arrival in New York in 1941, becoming the highest-paid name in the field: his sense of the gap between his "photography, pure and simple" and the money side, between the psychological and the society portraiture, never really went away.

We can only raise a cheer that the heritage issue has been fixed at last. It’s hard to know what exactly to salute Blumenfeld for today, but the attention given here to his early work as a collagist in the 1920s, and association with German Dada, was long overdue. Better known is his pioneering art photography, developed in Paris after his move there in 1936 – though it never earned him a living – including multiple exposures, solarized and contrast-printed work. Cecil Beaton tracked him down in 1938, saluting him as “incapable of compromise… better than fashion”, though Beaton still introduced him to Vogue, for whom Blumenfeld would produce some of that magazine’s greatest covers ever (an example from 1950, pictured above left). Blumenfeld entered fashion properly after his arrival in New York in 1941, becoming the highest-paid name in the field: his sense of the gap between his "photography, pure and simple" and the money side, between the psychological and the society portraiture, never really went away.

The Man Who Shot... had some tremendous archive material, including the photographer himself filmed at stage readings of his picaresque autobiography Eye To I. Even assuming the filmmakers had unrestricted access to Blumenfled’s family archive, their bias looks more towards the work than the life (was the extent of Blumenfeld’s bisexuality downplayed?) The story of escape from Nazi Europe might have merited more. Blumenthal was first interned by the French, then had great luck in getting US visas for his family in Marseilles, eventually reaching New York via Casablanca after a three-month journey, with one suitcase. He died in an unusual way too, in what all acknowledge was a planned suicide in July 1969: he ran up and down the Spanish Steps in Rome in summer heat, until he brought on a heart attack (having not taken his heart medicine intentionally).

With most of his photographic heritage still little known, this can only be the beginning of the rediscovery of Erwin Blumenfeld. Among colleagues, British photographer Rankin gave him the most effusive credit. Sometimes I wished the film's narrator, model Erin O'Connor, had gone just a tiny bit beyond her chosen neutral tone to emphasize that the work of a master has indeed been restored to us.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

there was the Barbican show

there was the Barbican show in - was it? - 1996. but otherwise, yes, Blumenfeld seemed to have rather disappeared from public view. and quite underservedly, given the quality of the work. I too wondered about the mention of his bisexuality. referencing it in only about 3 minutes did make you wonder - whether there were some family sentiments out there that made that a complicated issue still. but anyway, a fine programme, and glad to see the Somerset House exhibition signposted. though the early German work, the collages and Dada, did look fascinating, and worth knowing about independently of the photography.