Great Artists: In Their Own Words, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Great Artists: In Their Own Words, BBC Four

Great Artists: In Their Own Words, BBC Four

The BBC tries to cover up its own history of uptight, anti avant-garde conservatism

After the marvellous Great Thinkers: In Their Own Words, the BBC has once again rummaged through its documentary archives, this time to see what artists have to say for themselves. Artists are often not the most loquacious breed, which is why they communicate best in the language of images and objects. But it can certainly be instructive to get the lowdown straight from the horse’s mouth, even if it ends up being all performance and no insight.

Picasso’s art is turned into performance, though one that speaks more eloquently than any spoken statement can

In this first episode of three, subtitled The Future is Now, we concentrated on the years 1907 to 1939. This allowed us to kick off with Picasso’s savage and groundbreaking Les Demoiselle D’Avignon and finish off at that moment when artists were fleeing the old world for the new, in that great intellectual diaspora.

Picasso was, according to Great Artists, “a born self-publicist with a flair for finding the spotlight.” Strange then that there hardly exists any footage of him speaking on camera. The only filmed interview we appear to have was actually conducted by a French film crew in 1966, and the most interesting thing we learn is that he likes watching television.

But the most famous film of Picasso, the one in which he draws on glass and translucent paper, so capturing his astonishingly agile creative process, is not from the BBC either. A clip is shown here, but it was actually made by French director Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1956. What’s more, Clouzot’s film, The Mystery of Picasso, doesn’t record the artist speaking. Instead, Picasso’s art is turned into performance, though one that probably speaks more eloquently about his art than any spoken statement can.

Next is Matisse, cutting up pieces of coloured paper. He imparts a few wise words to remind us that talent alone is never enough – hard graft, and of course luck, play their decisive roles too. Derided by the public and dismissed by critics and those whose opinions mattered most to him, Matisse didn’t have much of the latter during the early part of his career. But boy did he work hard to the end. Confined to a wheelchair – and often to his bed – and unable to use a paint brush, he developed his gouaches découpés, his elegant paper cut-outs, inventive to the last.

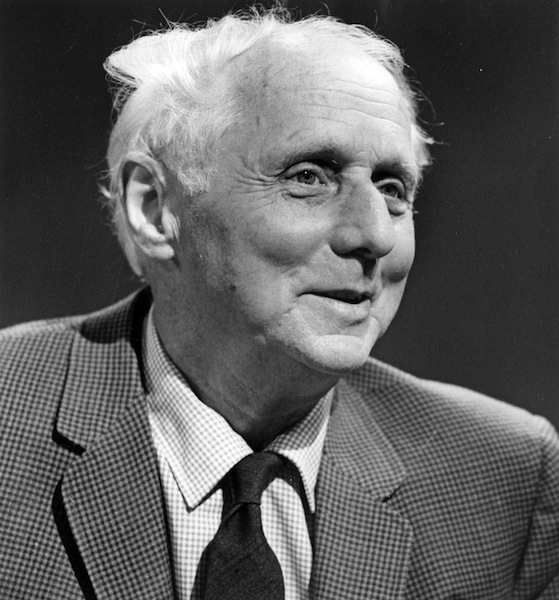

Max Ernst (pictured right) and Man Ray are the artists who could not only walk the walk but talk it. “Who made art history?” asks Ernst with a provocative flourish, in an interview for the BBC’s then leading arts programme, Monitor, in 1961. “Not the most reasonable people – the madmen did. If a painting is the mirror of a time, it must be mad to be a true image of what the time is.”

Max Ernst (pictured right) and Man Ray are the artists who could not only walk the walk but talk it. “Who made art history?” asks Ernst with a provocative flourish, in an interview for the BBC’s then leading arts programme, Monitor, in 1961. “Not the most reasonable people – the madmen did. If a painting is the mirror of a time, it must be mad to be a true image of what the time is.”

Of course, there was method in the madness of Surrealism, of which Ernst was the leading proponent, at least until Dalí thrust himself into the collective, or at least the public, consciousness and elbowed Ernst to the sidelines. This he did with not only his flamboyantly, kitschily deranged and violent paintings, but by his wildly eccentric performances on television chat shows. One doubts whether an ad for Alka-Seltzer would have been quite Ernst’s thing.

But if Ernst and Man Ray engaged with the camera, then Magritte desisted from talking to the camera altogether, at least for one BBC documentary about him. Instead he simply played up to his "bowler-hatted bourgeois clerk-cum-artist" image.

But this wasn’t just artists themselves talking, or not talking. There was an unending parade of talking-head experts, from the ubiquitous Grayson Perry to every loquacious television critic you can think of. Unlike the superb Great Thinkers series, you got the impression that there just wasn’t enough BBC footage of artists – great or otherwise – in the archives.

At one point the voiceover (Rebecca Front) reminds us of the deeply conservative tastes of the British public when it came to art. Of course, this must have been reflected by the corporation, and hence its lack of footage of early modernist masters and the reliance here on non-BBC, and non-British, material. After all, if the British Museum turned its nose up in the Fifties to an offer of a series of bargain-bucket Picassos, one could hardly have expected the BBC to positively embrace the avant-garde.

But the programme-makers didn't exactly own up to this philistine tendency on its own doorstop, but instead appeared to chide the uptight masses. By the time we get to the Sixties, and episodes two and three, this has changed – Pop art is suddenly sexy and Auntie is eager to get down with the kids.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Ep 2 seemed much more