In French, when you want to end a digression and get a conversation back on point, you say "revenons à nos moutons". It's a commonly used idiom, meaning literally "let's get back to our sheep", the sheep representing the actual subject under discussion. It also offers a way of looking at David Mamet's one-act play Squirrels, too, for no matter how far away their flights of imagination take them, the characters will always find their way back to their original theme, with a little help from an improbable animal – a squirrel, not a sheep, but you get the idea.

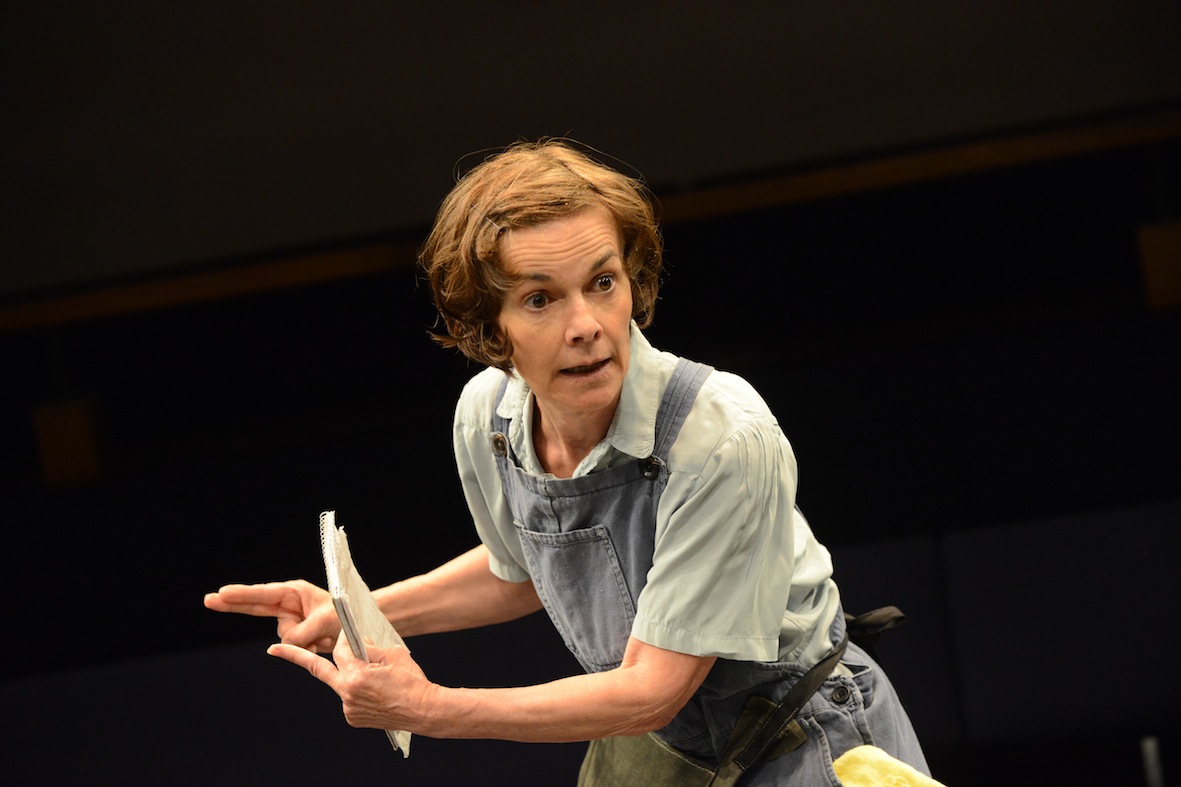

The action concerns Arthur, a writer who is trying and failing to write a story about a man and a squirrel in the park, and his secretary Edmond, who is supposed to be helping him. They take it in turns to improvise openings for it, which oscillate between the wildly melodramatic and the outrageously banal. Arthur (David Mallinson) takes every opportunity to exert his authority over Edmond, from dismissing his creative ideas to stealing his sandwich. They are joined periodically by their office's cleaning woman, who is also an aspiring writer. Her monologues are the play's best moments – sharp, witty, pathetic by turns, they make the often slow-moving squirrel patter feel worth the trouble. Janet Spencer-Turner (pictured left) puts in the stand-out performance of the evening, her sardonic subversion of the play's overt hierarchy a joy to watch.

They are joined periodically by their office's cleaning woman, who is also an aspiring writer. Her monologues are the play's best moments – sharp, witty, pathetic by turns, they make the often slow-moving squirrel patter feel worth the trouble. Janet Spencer-Turner (pictured left) puts in the stand-out performance of the evening, her sardonic subversion of the play's overt hierarchy a joy to watch.

Squirrels was first performed in 1974, and it's fascinating to see an early example of the style we know so well from later Mamet works like Glengarry Glen Ross. The dialogue overlaps and mutates, and so precise is the language that even the choice of a particular adverb is capable of pivoting the course of the drama.

Caryl Churchill's The After-Dinner Joke was first broadcast on television as a BBC Play for Today in 1978. Like Churchill's 2012 play Love and Information, this early work uses dozens of short, episodic scenes to tell the story, with recurring characters and themes building up into a kind of collage of impressions and ideas. In this, its first major stage revival, the five actors play over 40 characters, often only for a few minutes at a time.

It's a play for today still, even though all this time has passedThe central figure is Miss Selby (Lydia Larson), a young girl who wants to "do good" in the world. Her employer obligingly transfers her from his business to work in one of his charities, and she sets off to try and solve all of humanity's problems. Every possible ethical dilemma confronts her on the way: is it wrong to steal, if the money is going to the poor? Why is it necessary for fundraisers to humiliate themselves to earn money for a good cause? Who gets to decide who is truly in need of charity? With the cast-iron conviction that only comes with youth and naivety, she attempts to find the compassionate answer to all of these questions. The play is most interesting when it focuses on politics, and the discussion of whether it is possible to be charitable without being political. Again and again, we return to a scene between Selby and the mayor (Ben Onwukwe, pictured right with Lydia Larson), who are playing a word-association game intended to find something, anything, that can exist without a political dimension. The conversations that Selby has with her boss (David Gooderson) informs this, too – he is a very philanthropic man, but he refuses to support anything he deems 'political'. As Selby travels the world trying to find something uncontroversial enough for him to invest in, she eventually comes to the inevitable realisation that there is no such thing as an non-political cause.

The play is most interesting when it focuses on politics, and the discussion of whether it is possible to be charitable without being political. Again and again, we return to a scene between Selby and the mayor (Ben Onwukwe, pictured right with Lydia Larson), who are playing a word-association game intended to find something, anything, that can exist without a political dimension. The conversations that Selby has with her boss (David Gooderson) informs this, too – he is a very philanthropic man, but he refuses to support anything he deems 'political'. As Selby travels the world trying to find something uncontroversial enough for him to invest in, she eventually comes to the inevitable realisation that there is no such thing as an non-political cause.

Although it was written over 25 years ago, it's impossible not to see contemporary parallels everywhere in this play. Churchill's ideas apply easily to the war in Syria, for instance, and the ongoing debate over how much the UK should be contributing in foreign aid during our own economic difficulties. It was an excellent choice by Orange Tree trainee director Sophie Boyce – a play for today still, even though all this time has passed.

Add comment