Ibsen's Nora slammed the door on her infantilising marriage in 1879 but the sound of it has continued to reverberate down the years. In 2013, Carrie Cracknell directed Hattie Morahan in an award-winning performance at this theatre, last year Tanika Gupta profitably wove her story into that of colonial India at the Lyric, Hammersmith, Robert Icke's Children of Nora is due to open in Amsterdam in April and Samuel Adamson's exploration of relationships in four distinct periods, Wife, at the Kiln last summer, echoed Nora's experience.

Translation can spell liberation. Where Victorian English might be distancing, a new version of a play originally written in another language immediately benefits from the immediacy of familiar speech. Stef Smith began as a poet and her enjoyment of language in different registers, with a hint at period changes, is one of the pleasures of this piece. Here there are three Noras at three stages of liberation: 1918 when (some) women earned the right to vote; 1968 just after the legalisation of abortion and when the contraceptive pill was coming into general use; and 2018 as the #MeToo movement gathered momentum.

Translation can spell liberation. Where Victorian English might be distancing, a new version of a play originally written in another language immediately benefits from the immediacy of familiar speech. Stef Smith began as a poet and her enjoyment of language in different registers, with a hint at period changes, is one of the pleasures of this piece. Here there are three Noras at three stages of liberation: 1918 when (some) women earned the right to vote; 1968 just after the legalisation of abortion and when the contraceptive pill was coming into general use; and 2018 as the #MeToo movement gathered momentum.

Smith has not so much adapted Ibsen as exploded the original while adding a pacey intensity. Some names are changed, but the bones of the story are here: Nora's apparently perfect marriage and family life are threatened by the impending revelation by a blackmailer of her fraudulent acquisition of money to aid her husband's recovery from a breakdown. Christine, an old friend of Nora's and a previous lover of the would-be blackmailer, an employee of Nora's husband, intervenes, but in the end all is revealed and Thomas (Ibsen's Torvald) shows himself to be weak and unworthy of his wife's love. She walks out on the marriage.

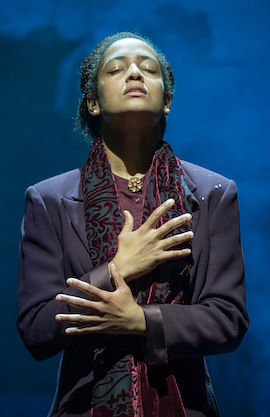

Smith's three Noras are sometimes interchangeable, sometimes very much of their time. They occasionally speak in chorus or use the third person to describe their/her predicament, but they are also differentiated, by both class and demeanour. Anna Russell-Martin is a tough, hard-talking contemporary Scot, Natalie Klamar is an Estuary Sixties woman hesitantly discovering new sexual possibilities, while Amaka Okafor (pictured right) has an elegant, middle-class dignity as the 1918 Nora. Each has a secret means of escape from the day-to-day: sugar for the earliest Nora; pills, "mother's little helpers", in the Sixties, and alcohol in 2018. Luke Norris, Thomas in every case, slips into altered speech and posture as necessary. All three Noras also play three Christines. The whole thing – a tense hour and 45 minutes – is beautifully controlled and choreographed in Elizabeth Freestone's sympathetic direction. Tom Piper's abstract set – three lit doorways with the suggestion of an icy river beyond – with audience on three sides of a thrust stage, and Michael John McCarthy's moody soundscape, often suggestive of heartbeats, complete Nora's world.

Smith's three Noras are sometimes interchangeable, sometimes very much of their time. They occasionally speak in chorus or use the third person to describe their/her predicament, but they are also differentiated, by both class and demeanour. Anna Russell-Martin is a tough, hard-talking contemporary Scot, Natalie Klamar is an Estuary Sixties woman hesitantly discovering new sexual possibilities, while Amaka Okafor (pictured right) has an elegant, middle-class dignity as the 1918 Nora. Each has a secret means of escape from the day-to-day: sugar for the earliest Nora; pills, "mother's little helpers", in the Sixties, and alcohol in 2018. Luke Norris, Thomas in every case, slips into altered speech and posture as necessary. All three Noras also play three Christines. The whole thing – a tense hour and 45 minutes – is beautifully controlled and choreographed in Elizabeth Freestone's sympathetic direction. Tom Piper's abstract set – three lit doorways with the suggestion of an icy river beyond – with audience on three sides of a thrust stage, and Michael John McCarthy's moody soundscape, often suggestive of heartbeats, complete Nora's world.

Although there is a distinct feminist call to arms here, there is also an acknowledgement that things have changed in 100 years. Women can vote, they can work, have loving relationships with each other without embarrassment and choose whether to have children, but without financial independence choice is still limited. And this is not restricted to women: Nathan (Ibsen's Krogstad: played by Mark Arends, pictured above left) is just as desperate to do the best for his family in pinched circumstances, just as prone to break society's rules to do so as Nora. Choice, the freedom to choose, is a theme that runs through the play. It is notable that Smith's Nora – in all her manifestations – seems unsure whether her children are a barrier to her self-realisation, that she wishes them gone because she lacks the confidence to be a good enough mother or she simply adores them. Or perhaps all three. Freedom is a desirable ambition, but achieving it is complicated. The play ends with a half-completed sentence on the idea.

Add comment