An infamous international financier, with a contacts book that includes presidents and dictators, a dark dossier on everyone he’ll ever need to bribe or blackmail, and a cold, ruthless heart, spends a long night in downtown New York trying to save his business. And he’ll go to any lengths to do it, including pimping his own son.

Terence Rattigan wrote Man and Boy in the Sixties and set it in the Thirties, his evil protagonist partly based on a crooked Swedish businessman finally undone by the Great Depression. But it screams of the here and now, of Robert Maxwell, Bernie Madoff and, particularly, of Jeffrey Epstein, its chilling resonance crashing off the stage in waves.

It’s a late and rarely produced work, generally perceived as a sub-par Rattigan that has been occasionally saved by stars making hay with the diabolical Romanian entrepreneur Gregor Antonescu, whether David Suchet in London in 2005, or Frank Langella on Broadway in 2011. At the Dorfman, the ever-fabulous Ben Daniels merits equal praise, though I’d venture that the play itself feels a little better than its bad rep would suggest – unlikely and ultimately undercooked, yes, but nonetheless hugely entertaining and provocative. That may be down to director Anthony Lau’s decision to mine its black comedy for all its worth.

The action takes place in a Greenwich Village apartment, in 1934. Antonescu, who has made his name in radio, oil and dodgy dealings, dubbed "the mystery man of Europe", is facing his biggest crisis: a planned merger with American Electric that would have saved his business has suddenly been taken off the table, due to questions over his accounts. Pursued by journalists, Antonescu has taken sanctuary in his estranged son’s apartment, where he has planned a secret meeting with American Electric boss, Mark Herries (Malcolm Sinclair, pictured above right, with Daniels), to change his mind.

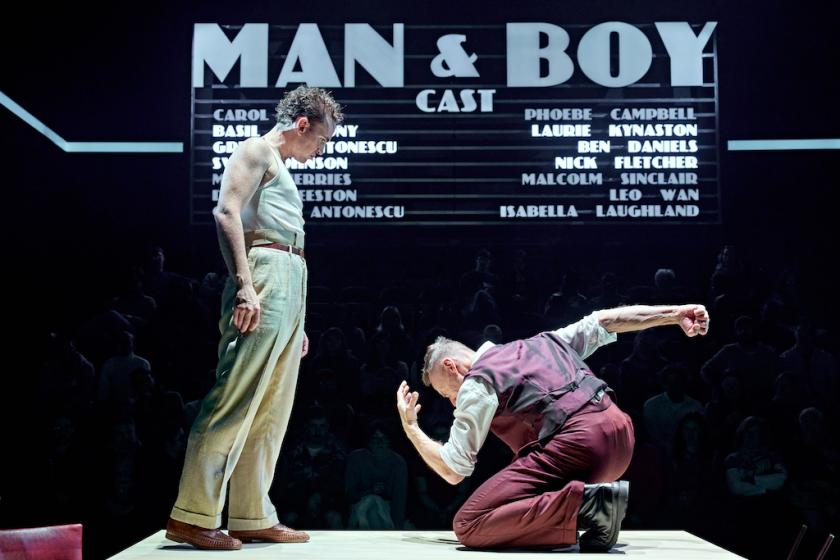

The designers smartly set the tone – Thirties New York, jazzy, seedy, nocturnal – in ways that are abstracted but remarkably effective. Georgia Lowe’s set has an unusual, green baize-like flooring and scant props – a piano, a clothes rack, a radio, a few tables; high up on one wall is a giant, Thirties Hollywood-style credit card (with the names of the play’s cast and characters); Elliot Grigg’s massive lighting rig looms over the stage, sometimes passive, at others veering dramatically in exaggerating angles. The nature of the apartment, referred to frequently as “a dump”, is left to our imagination. In its place is the sense that we’re watching a game being played, under lights, heightened by the actors constantly moving the tables around, often climbing atop them, as they manoeuvre themselves and each other.

Rattigan first establishes the relationship between the son, who now calls himself Basil Anthony (Laurie Kynaston) and his girlfriend of six months, Carol Penn (Phoebe Campbell). He’s a piano player in a local club, she an aspiring actress, both broke, clearly fond of each other, but he is closed, private, withholding his real identity, teetering on alcoholism.

The likeable Carol is excitedly listening to the news about Antonescu on the radio, much to Basil’s annoyance, when the man himself makes an unexpected arrival; it’s been five years, and the last time they met the son made a hapless attempt to shoot his unloving dad. But here Gregor is, as though none of that happened, in a resplendent maroon suit, flipping between Romanian, French and English on a dime but heavy accent intact, which he appears to use as a weapon. He is at once charming, flamboyant, shifty and dangerous, grandiose yet ridiculous, and quite mesmerising.

Daniels has a field day with the man, boldly going for the larger than life, using his innate, catlike physicality to both preen and intimidate. I weirdly couldn’t stop thinking of Bela Lugosi, and in a way Antonescu is a vampire, gleefully feeding of his victims.

“Liquidity and confidence” is his mantra, his way of surviving the Depression. But corruption plays a large part, too. With the dossier provided by his sidekick, Sven (Nick Fletcher), which reveals Herries' homosexuality, Gregor prepares a cunning plan, involving the ignorant Basil as bait. When Herries (Malcolm Sinclair) arrives with his bullish but out-of-his-depth accountant (Leo Wan), the Romanian gets to work.

If the first half sees Antonescu at his diabolical best, while setting up a bleak confrontation between father and son, the second fails to deliver on that tension, settling for a rather conventional comeuppance with few surprises and little satisfaction in how the central relationship plays itself out. There could have been real tragedy here.

Nonetheless, Daniels continues to hold the attention, adeptly shifting his physicality from strength to frailty. And he’s ably supported by the whole cast, with Fletcher coming into his own as the kind of loyal facilitator who, nonetheless, has his own exit plan expertly in place, and with the welcome second half addition of Isabella Laughland (pictured above) as Gregor’s wife Countess Antonescu – the title bought, of course. In her garish fur coat, lusty and self-interested, she is as brutally funny as her husband – as ever, it’s the villains who get all the best lines.

Add comment