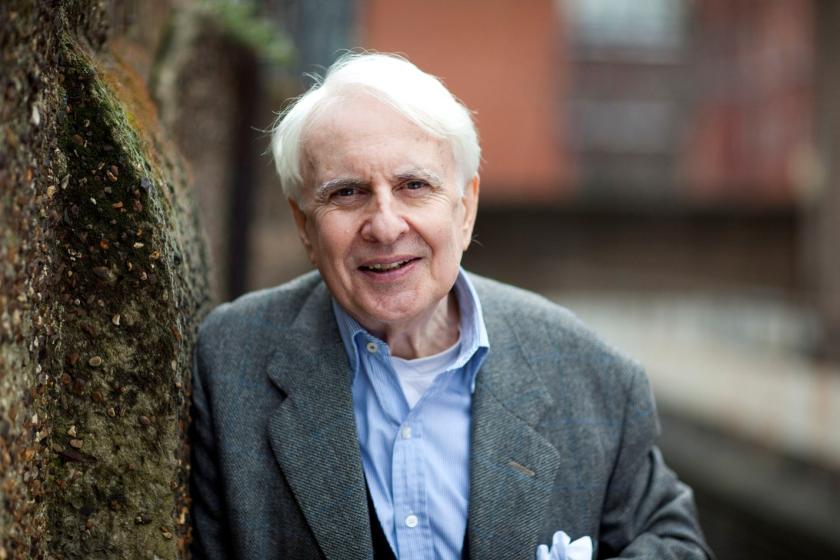

There is a simple explanation to why Cardiff-born Peter Gill has never directed in his home city, despite the fact that many of his own plays are set in the Catholic, working-class Cardiff of his youth. “I’d never been asked,” states Gill matter-of-factly; “it’s just a trade; it’s not a magical world. You have to ask me to do things.”

There is something bracing about the lack of sentimentality with which Gill addresses the question of homecoming. It fits with the setting of our conversation too: a big, airy rehearsal room at the newly-rebuilt Sherman Theatre in the heart of Cardiff’s student-dominated inner suburb of Cathays, where the director, now 72, has just finished “exhausting” work on some rehearsal specifics with a few of his actors. Like the new foyer area, the whitewashed walls and high ceilings give the impression of a blank canvas; rather than a return to the past, Gill’s return is part of Welsh theatre’s new beginnings.

People from outside these islands must think we’re all potty

John McGrath, Artistic Director of National Theatre Wales, admits that the director he calls a “legend” was top of his list of people to work with when the company was founded. Known as a great director of Chekhov plays, Gill was persuaded by McGrath to make his directorial debut in his home city – 55 years after he left for London - with a return to A Provincial Life, his own stage adaptation of a Chekhov novella set in 1890s Russia.

Gill expects the play to resonate with a contemporary audience not only because it is “a lovely story” and Chekhov “a wonderful writer” but also because it is about “a very real question… of moral responsibility to notions of equality and justice.” A Provincial Life follows one young man’s struggle to exchange his privileged position for the life of a worker. Gill claims not to be able to put his finger on why he was so taken with it prior to its original run at the Royal Court Theatre in October 1966. But given that, whatever the question, Gill’s talk turns so often to this concept “equality” – something he describes as a “political non-talking point in the last 20 years” – it is clear to see the root of the director’s affinity with Chekhov (and also DH Lawrence), which now stretches over a career spanning almost half a century.

Gill expects the play to resonate with a contemporary audience not only because it is “a lovely story” and Chekhov “a wonderful writer” but also because it is about “a very real question… of moral responsibility to notions of equality and justice.” A Provincial Life follows one young man’s struggle to exchange his privileged position for the life of a worker. Gill claims not to be able to put his finger on why he was so taken with it prior to its original run at the Royal Court Theatre in October 1966. But given that, whatever the question, Gill’s talk turns so often to this concept “equality” – something he describes as a “political non-talking point in the last 20 years” – it is clear to see the root of the director’s affinity with Chekhov (and also DH Lawrence), which now stretches over a career spanning almost half a century.

And despite his characteristically unsentimental expression of “a strong affection for south Wales, which is the only Wales I know” rather than outright patriotism and his “coming from a generation that trained itself to feel British”, Gill does see in his fellow countrymen a unique commitment to his own brand of politics. “The Welsh are the only people in these islands who have a genuine sense of finding equality attractive; they have no problem with it, they admire it.” He does not see this tradition of Wales being largely camped to the left of mainstream British politics – Aneurin Bevan is a hero – as a cause for the break-up of the union, and he points out some interesting parallels with his research for A Provincial Life. “In the 1890s in Czechoslovakia, you had to speak German to get on. And there were a lot of brilliant young Czechs came up who were not going to speak German.” But Gill refuses to “get involved with any notion of [nationalistic feeling]. You’ve only got to look at the map; people from outside these islands must think we’re all potty!”

Asked to pinpoint the genesis of his interest in theatre – which is total to the point where he is sometimes envious of the stage manager’s level of access to aspects of a production where “the writer feels marginalised from the whole process” – again Gill reaches for an explanation rooted in specific socio-political developments. “We were beneficiaries of the Butler Act,” he says, referring to the Education Act of 1944 that “allowed boys of our class to have aspiration” by sending them to grammar schools. Gill’s own grammar school, Roman Catholic St Illtyd’s College, turned out to be “very special”. “I can’t put my finger on it, but there must have been something about it that made for a certain artistic appetite,” he says as he reels off a list of his friends and others he is still in touch with from his schooldays, counting among them a poet and academic, a painter and a sociologist who believes that the likes of Gill were “airlifted out of the working class so that we wouldn’t be trouble”.

Asked to pinpoint the genesis of his interest in theatre – which is total to the point where he is sometimes envious of the stage manager’s level of access to aspects of a production where “the writer feels marginalised from the whole process” – again Gill reaches for an explanation rooted in specific socio-political developments. “We were beneficiaries of the Butler Act,” he says, referring to the Education Act of 1944 that “allowed boys of our class to have aspiration” by sending them to grammar schools. Gill’s own grammar school, Roman Catholic St Illtyd’s College, turned out to be “very special”. “I can’t put my finger on it, but there must have been something about it that made for a certain artistic appetite,” he says as he reels off a list of his friends and others he is still in touch with from his schooldays, counting among them a poet and academic, a painter and a sociologist who believes that the likes of Gill were “airlifted out of the working class so that we wouldn’t be trouble”.

Gill answers my questions with a straight bat, but there is a slightly mischievous undertone to this last point. One gets the distinct impression that Gill would quite like to have been trouble; the new politics, he claims, “have everybody who believes in equality having to spend most of their time proving [they’re] not Stalinist.” But despite the politics, it is his passion for theatre that has made his name. In discussing the differences – or lack thereof – between text-based and non-text-based drama, something that has got Gill exercised in the past as a “totally false” dichotomy – “the idea that Stanislavsky invented Chekhov is a lie” – Gill takes us right back to the beginning. “In the end, what [the Greeks] invented, which was a thing by one person made to come alive by another group of people, is still the most efficient form. Film is based on it. Nobody shoots a film without a text.” (Picture below: cast of A Provincial Life in rehearsal)

Gill understands the reason critics are tempted to draw a line between text-based plays in traditional buildings and more avant-garde situational forms of drama. As the first Artistic Director of the Riverside Studios in Hammersmith, Gill established the venue at the cutting edge of London arts by mixing Chekhov and Shakespeare with experimentalists like the great Polish artist-director Tadeusz Kantor and the Brecht-influenced South African writer-director Athol Fugard. But to Gill, all theatre is situational, requiring leaps of audience imagination. Referring to his forthcoming production, he restates his perpetual directorial task: “We still have to make the Sherman on that night work as a theatre. What we’re going to do is an imaginary gesture of another kind.”

Gill understands the reason critics are tempted to draw a line between text-based plays in traditional buildings and more avant-garde situational forms of drama. As the first Artistic Director of the Riverside Studios in Hammersmith, Gill established the venue at the cutting edge of London arts by mixing Chekhov and Shakespeare with experimentalists like the great Polish artist-director Tadeusz Kantor and the Brecht-influenced South African writer-director Athol Fugard. But to Gill, all theatre is situational, requiring leaps of audience imagination. Referring to his forthcoming production, he restates his perpetual directorial task: “We still have to make the Sherman on that night work as a theatre. What we’re going to do is an imaginary gesture of another kind.”

And it is bound to be a memorable night at the rebuilt Sherman, a theatre Gill remembers being built in the first place. At the Riverside, where Gill’s four years at the helm revolutionised the venue, he began with an adaptation of The Cherry Orchard. In The Sunday Times, Bernard Levin wrote that “it is good to salute the opening of a new theatre… with almost unqualified praise… Mr Gill and his cast have sought success in the only place it can be found: inside themselves and the play. The effect is magical; The Cherry Orchard has almost never, in my experience, been at once so harrowing and so glittering; nor its fragile rhythms so finely, surely spun, its development so natural, human and real.” If A Provincial Life can do something for Sherman Cymru akin to what The Cherry Orchard did for the Riverside Studios in 1978, it will be yet another triumph for NTW and John McGrath’s ability to pick a winner. “Just a trade” the theatre business might be, but even if Peter Gill won’t say it himself, he is in the business of magic creation.

- A Provincial Life at Sherman Cymru from 1 to 17 March

Add comment