It’s a brave company that embarks on a staging of John Steinbeck’s award-winning 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath. A grim study of human goodness in an unrelentingly cruel universe, it’s a long slog for both cast and audience.

Steinbeck based his novel on his experiences in 1936 of reporting for a San Francisco newspaper on the US migrant camps known as Hoovervilles, after the President who set them up. But relief for their residents — escapees from the US’s economic collapse in the early 1930s and the Dust Bowl that then destroyed over-farmed land in Texas and Oklahoma — would have to wait until FDR’s policies begin to turn the tide later in the decade and a war economy sealed the deal.

Adapted by Frank Galati and directed by Carrie Cracknell, this National Theatre production has a fine cast, as well as inventive set and sound design. Yet its source material, the soul-destroying 2,000-mile journey to California undertaken by this family of tenant-farmer Okies in search of honest toil, is inescapably bleak.

The virtue of the 1940 film adaptation was that the Joad family’s old jalopy was at least moving: this forward motion wasn’t progress but it did at least represent flight. The screen version could also provide numerous extras and a sense of trundling from the Panhandle to the Mojave desert and on to the fruitgrowing lands of California, however blighted the outcome. But the Lyttelton’s stage obliges the Joad jalopy mostly to turn in circles. It’s an apt metaphor for the viciousness of their situation — victims of the economy, the banks, prejudice, human-triggered natural disaster — but it adds to the claustrophobia.

Alex Eales’s set design is suitably evocative. In the first scene, a long shaft of light crosses the dark stage, at the end of which is a man struggling at a 45-degree angle to the ground as high winds stop him in his tracks. It’s the perfect image to introduce the beleaguered Okies, their produce plummeting in price, their top soil worked to death, drought finishing off their crops and high winds blowing the resulting dust around to create a daytime blackout.

Alex Eales’s set design is suitably evocative. In the first scene, a long shaft of light crosses the dark stage, at the end of which is a man struggling at a 45-degree angle to the ground as high winds stop him in his tracks. It’s the perfect image to introduce the beleaguered Okies, their produce plummeting in price, their top soil worked to death, drought finishing off their crops and high winds blowing the resulting dust around to create a daytime blackout.

The Joads will similarly journey on against every kind of obstacle after setting out from their derelict shack, 12 people piled into an ancient vehicle. They reach a dreary tented Hooverville camp along the way, which they have to run from when local law enforcement comes to burn it down (executed effectively with just an orange projection on the back wall and the sound of fierce burning). Dodging hostile locals, who view them as scum, they find a relative paradise, a clean and humane camp, but can’t afford to stay there. Then it’s on to a fruit farm behind a metal-grill fence with razor wire along the top, patrolled by armed guards and looking like a different kind of camp. A biblical flood forces them to seek shelter in a barn, looking like a different kind of family.

Their band of 12 has been pared down, its ties loosened, possibly permanently; in the final moments just one remains onstage, the Joads’ married daughter Rose of Sharon (Mirren Mack, pictured below with Anish Roy as Connie), enacting an extraordinary act of human charity. All of this is achieved with minimal means, the token scenery seamlessly wheeled on and off, camps struck with amazing speed. The design also makes good use of a long trough of water at the front of the stage, invisible to the audience. For extra vocal colour, there is a small band of musicians, led by singer-guitarist Robyn Sinclair, whose rich bluesy voice delivers portentous songs about suffering and refugees, a chorus whose aim is to elevate the Joads to universal emblems of beleaguered labour.

The cast, as are the Joads, is led by Cherry Jones as Ma, a Broadway stalwart who appears here with hair scraped back, shod in solid brown ankle boots. Her long floral dress is one of the only sources of colour on the stage. Ma is a soother of wounds, and a sort of soothsayer, too, who predicts to her dispirited husband (Greg Hicks) that change is on its way. Her spirit keeps the family on the road though not always together. Jones has to pull off the task of being tough without being heartless, decent without being sentimental, and mostly succeeds.

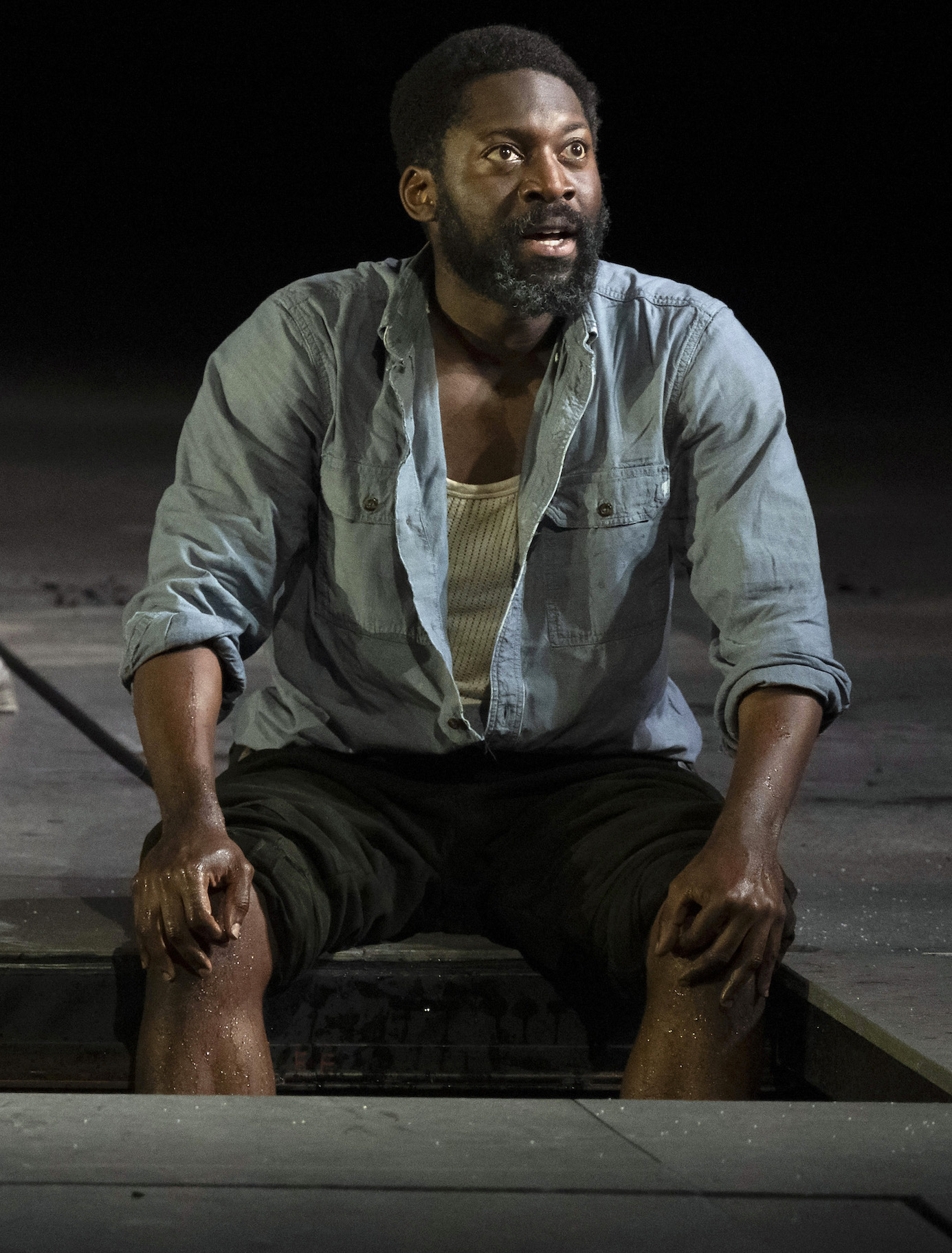

The other source of goodness is Jim Casy, the former livewire preacher who travels part of the way with the Joads. Natey Jones (pictured above) turns in another great performance here as a troubled man who has a vision that all the souls in the world are one big soul, always there to help each other. But he is, by his own definition, a fornicating sinner. In restitution, he too commits an act of selflessness as leader of the strikers who are refusing to work for derisory sums at the farm that’s exploiting them. There’s a total believability to Jones’s acting, never a false note.

Plaudits too for Mirren Mack’s fragile, anxiety-riddled Rose, whose spineless husband Connie (Anish Roy) leaves her; Michael Shaeffer as Uncle John, a sad and haunted man; Tom Bulpett as Noah, the Joads’ eldest son, damaged at birth, who gives his “slowness” a convincing form of sweetness, with a gentle voice to match; and to Tucker St Ivany as Al, the third-oldest Joad boy, a 16-year-old Romeo with a punky, jittery presence. Only Harry Treadaway as Tom Joad, the second son, whose temper has led him to jail for killing a man, seems a little ill at ease in his role, delivering it at a steady pitch that at times borders on monotonous.

Plaudits too for Mirren Mack’s fragile, anxiety-riddled Rose, whose spineless husband Connie (Anish Roy) leaves her; Michael Shaeffer as Uncle John, a sad and haunted man; Tom Bulpett as Noah, the Joads’ eldest son, damaged at birth, who gives his “slowness” a convincing form of sweetness, with a gentle voice to match; and to Tucker St Ivany as Al, the third-oldest Joad boy, a 16-year-old Romeo with a punky, jittery presence. Only Harry Treadaway as Tom Joad, the second son, whose temper has led him to jail for killing a man, seems a little ill at ease in his role, delivering it at a steady pitch that at times borders on monotonous.

It’s easy to see why a piece about the forces that drive law-abiding, hard-working people to become migrants would have attracted the NT’s attention, and this team makes a good fist of it. But it’s still a difficult piece to digest, and maybe is better served on the page than on the stage.

The Grapes of Wrath at the NT Lyttelton, in rep until 14 September

Add comment