Becky Shaw, Almeida Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Becky Shaw, Almeida Theatre

Becky Shaw, Almeida Theatre

Gina Gionfriddo's comedy of bad manners and sexual mores is too clever by half

Becky Shaw is lonely, unattractively needy, nervous, hungry for affection, affirmation, security. We are all Becky Shaw. That’s a gross generalisation, of course – but then, generalisation is the language of Gina Gionfriddo’s play, which premiered in Louisville, Kentucky, prior to a 2009 off-Broadway run.

A smart-mouthed, brittle comedy about the slippery politics of sex, dependency and what we choose to call love, the piece is crammed with zingers, but often feels like little more than a US sitcom: a well-crafted, sharply written sitcom, but for all its style a work that seems more concerned with turn of phrase than subtlety of character or plot. That, while it might sparkle in a 30-minute format, in a longer, more demanding form feels somewhat overstretched.

In a slick but slightly soulless production by Peter DuBois – who also directed the American stagings – it’s an intermittently amusing, but ultimately rather pat, examination of 21st-century relationships. Max (David Wilson Barnes, who originated the role in the US) and Suzanna (Anna Madeley) are de facto adoptive siblings; Susan (Haydn Gwynne) is Suzanna’s toxic mother. When Suzanna’s father dies, and Susan shacks up with a red-neck chancer considerably her junior, Max steps in to help Suzanna deal with the emotional and financial fallout.

Since he’s clearly been carrying a torch for Suzanna for years, this should be the perfect opportunity for Max to pounce – particularly since he has no moral qualms about sexual exploitation, still less any romantic illusions about the dirty business of love. Everybody uses one another, he reasons; and “love is a happy by-product of use”. But while he can, and does, seize the moment to get it on with the neurasthenic Suzanna – who is reeling from the posthumous revelation that the father she thought she was close to was hiding secrets, among them a possible long-term gay affair – Max is far too emotionally constipated to admit that he wants a romance that might develop further.

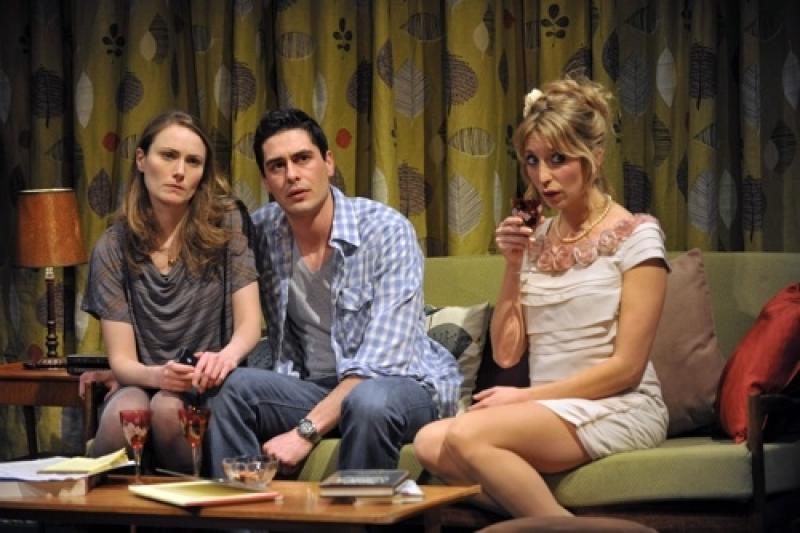

His reticence sets in train events that become increasingly damaging. Suzanna takes his advice to find herself a hobby, goes off on a skiing trip, meets sensitive Andrew (Vincent Montuel) and marries him in haste in Las Vegas; and the pair of them set Max up on a date with Andrew’s flaky friend Becky (Daisy Haggard, pictured right with Barnes). This titular character was, according to Gionfriddo, partly inspired by Becky Sharp of Vanity Fair – but she bears scant resemblance to Thackeray's creation. Her liaison with Max is, predictably, disastrous. Becky is frilly-frocked, impecunious, kooky and eager, Max money-driven, snobbish, rude and contemptuous. On their ill-starred evening out, they get held up by a gun-toting street hood; and at the end of the traumatic night, he opportunistically fucks her anyway. When Becky imagines their desultory coupling meant they had a future, and Max won’t return her calls, she starts threatening suicide. It’s the emotional equivalent of a Valentine’s Day massacre - though it's not always clear who's firing the bullets.

His reticence sets in train events that become increasingly damaging. Suzanna takes his advice to find herself a hobby, goes off on a skiing trip, meets sensitive Andrew (Vincent Montuel) and marries him in haste in Las Vegas; and the pair of them set Max up on a date with Andrew’s flaky friend Becky (Daisy Haggard, pictured right with Barnes). This titular character was, according to Gionfriddo, partly inspired by Becky Sharp of Vanity Fair – but she bears scant resemblance to Thackeray's creation. Her liaison with Max is, predictably, disastrous. Becky is frilly-frocked, impecunious, kooky and eager, Max money-driven, snobbish, rude and contemptuous. On their ill-starred evening out, they get held up by a gun-toting street hood; and at the end of the traumatic night, he opportunistically fucks her anyway. When Becky imagines their desultory coupling meant they had a future, and Max won’t return her calls, she starts threatening suicide. It’s the emotional equivalent of a Valentine’s Day massacre - though it's not always clear who's firing the bullets.

Gionfriddo, who has written for the TV series Law & Order, certainly has a deft way with dialogue. “Intimacy is a prescription for misery,” snaps Susan, who is a big believer in the virtue of the convenient lie. But if what’s being said often sounds clever, there’s a deep seam of shallow pop psychology running through it. Max is incapable of expressing his feelings, and defends himself with aggressive cynicism, because of his calamitous parents; Suzanna – a psychology PhD student who plans to become a therapist – seeks self-worth in fretting about others, specifically her waspish mother, who has MS as well as a lover whom her daughter sees as unsuitable; Andrew is an enabler who hunts lame ducks – first Suzanna, then Becky – and keeps them lame by hobbling them with pseudo-caring platitudes. It’s all very neat, but behind the dazzle of the epigrams there’s little in the way of complex characterisation or plot.

Still, as in most generalisations, there are grains of truth here that will allow most of us to empathise at least once or twice. And Gionfriddo spreads her sympathies around pretty even-handedly; everyone’s a bit right, everyone’s a bit wrong, and they’re all equally blinkered. DuBois keeps the whole thing zipping along, and the cast wrings plenty of abrasive comedy from the bitter witticisms, the bungled connections and the toe-curling social discomfort. In the end, though, that’s not quite enough.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

Add comment