Sunlight bounces off Derbyshire stone, buskers strum on the Pavilion Gardens bandstand and there’s improvised Shakespeare on the streets: it’s Festival time again in Buxton. Frank Matcham’s Opera House doesn’t present a particularly festive appearance to the street – he had to squeeze it in next to the Winter Gardens, after all – but once you’re inside, it’s a positive confectioner’s shop of ceramic tiles, coloured glass and swirling gilt, quite as breezily ritzy as any of Matcham’s West End creations. Painted cartouches on either side of the stage proclaim the twin gods of the British musical-dramatic universe in the year 1903: Shakespeare and Sullivan.

None of this is news to opera lovers, for whom Buxton has developed a reputation as a sort of Wexford of the Peak. Recent Festivals have seen productions of such rarities as Messager’s Fortunio, Dvořák’s The Jacobin and Cornelius’s The Barber of Baghdad. This year’s offerings didn’t seem quite as striking: concert performances of Gustave Charpentier’s Louise sat alongside Verdi’s Giovanna d’Arco, Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. Arts organisations have to meet their financial targets, of course, and anyone churlish enough to wish that Buxton had staged Louise rather than add further to the current EU Donizetti Mountain would have been disarmed by the sheer quality of Elijah Moshinsky’s handsome new production of Giovanna d’Arco.

Temistocle Solera based his libretto on Schiller’s The Maid of Orleans; a fact that still troubles historians and lovers of German literature alike. In Verdi and Solera’s re-telling, Joan of Arc has a love affair with Charles VII of France before dodging the stake to die in battle and rise miraculously from the dead during her own funeral. Moshinsky did this the courtesy of taking it on its own terms – cue giggles from the audience as evil spirits appeared in red devil-masks complete with horns; which, arguably, is no more than Verdi’s ditzy waltz tune (complete with accordion effects) of a Demons’ Chorus deserves.

It looked gorgeous, though. A glowing cloudscape rolled above the two black marble walls of Russell Craig’s set; with imaginative lighting by Malcolm Rippeth plus a bit of smoke, the various tableaux were reflected back like oil paintings – tableaux being the operative word. With characters dressed in colourful more-or-less period costumes, Moshinsky assembled magnificent stage-pictures in ensemble scenes. Individual details, however, were less effective, particularly a tendency to bring singers to the front of the stage and let them stand and deliver. That broad-brush approach was most noticeable in David Cecconi’s account of Giovanna’s father Giacomo: ravishingly sung, with a warm, mahogany baritone but little of the tortured menace you might imagine from a character whose religious fanaticism drives him to condemn his own daughter to death.

It looked gorgeous, though. A glowing cloudscape rolled above the two black marble walls of Russell Craig’s set; with imaginative lighting by Malcolm Rippeth plus a bit of smoke, the various tableaux were reflected back like oil paintings – tableaux being the operative word. With characters dressed in colourful more-or-less period costumes, Moshinsky assembled magnificent stage-pictures in ensemble scenes. Individual details, however, were less effective, particularly a tendency to bring singers to the front of the stage and let them stand and deliver. That broad-brush approach was most noticeable in David Cecconi’s account of Giovanna’s father Giacomo: ravishingly sung, with a warm, mahogany baritone but little of the tortured menace you might imagine from a character whose religious fanaticism drives him to condemn his own daughter to death.

Is that expecting too much, from a mid-19th century potboiler? The thing is, other aspects of the performance really did cohere. There was Ben Ben Johnson's performance as a milksop Carlo whose voice gradually darkened and richened as passion and a sense of destiny consumed him. There was the distinguished presence of Stuart Stratford, conducting the Northern Chamber Orchestra, who navigated the shuddering basses and dizzying moodswings of Verdi’s score with considerable verve.

Above all, there was Kate Ladner’s central performance as Giovanna herself (pictured above with Johnson): heroic but believably human, whether recoiling as if scalded from Carlo’s first kiss, or conveying both resignation and steely determination before and after battle. She has a voice that can vault powerfully over Verdi’s most taxing flights, and yet hang pale and weightless in the air in the aftermath of a boisterous ensemble. Along with Stratford’s conducting, Ladner’s performance – more than anything else in a fine cast and a generally effective production - convinced you that there’s something worth exploring beneath Giovanna d’Arco’s melodramatic surface.

A specially-composed fanfare in the best Bayreuth style summoned us into the following afternoon’s Lucia di Lammermoor: an opera which doesn’t need any special pleading, and didn’t receive any in Stephen Unwin’s spartan production. Back and front cloths showed romantic landscapes from the Walter Scott era, yet the characters were dressed in drab, vaguely 1950s costumes. Raffishly tilted trilbys suggested that Unwin saw Donizetti’s Jacobites and loyalists as rival mobsters, and it’d be good to have seen those parallels brought out a little more vividly in the three almost static scenes that preceded Act Two’s explosive wedding. Played out on a gloomy, all-but-empty stage, the first half of the opera seemed to drag, and the decision to drop the curtain and pause after each scene didn’t help. The orchestra, too, didn’t sound quite as focused under Stephen Barlow as it had the previous night, though Barlow had a nice way of lingering briefly over a touch of Romantic colour – a horn call here, a clarinet solo there – before launching off into another chugging Donizetti cabaletta.

So Elin Pritchard’s Lucia (pictured left) came across, initially, as merely sweet-voiced and fragile; nicely matched (in terms of vocal timbre) to Adriano Grazia, as her forbidden lover Edgardo, while as her brother Enrico, Stephen Gadd conveyed a cool arrogance rather than active evil: a Germont père, rather than a Scarpia. When Act Two ignited in that wedding scene (with some powerful work from the Buxton Festival Chorus), so too did the individual performances. Bonaventura Bottone made something creepily believable of Arturo, and Andrew Greenan’s sonorous Raimondo drew himself up to his full dramatic height. Pritchard pealed out the glassy high notes of her mad scene with an eerie intensity, while Grazia’s tone curdled chillingly in the final moments. There were a lot of school-age students in this matinee audience. First-timers? Their animated reactions as we headed back out into the daylight suggested that by the end, at least, they’d felt something of what opera can do.

So Elin Pritchard’s Lucia (pictured left) came across, initially, as merely sweet-voiced and fragile; nicely matched (in terms of vocal timbre) to Adriano Grazia, as her forbidden lover Edgardo, while as her brother Enrico, Stephen Gadd conveyed a cool arrogance rather than active evil: a Germont père, rather than a Scarpia. When Act Two ignited in that wedding scene (with some powerful work from the Buxton Festival Chorus), so too did the individual performances. Bonaventura Bottone made something creepily believable of Arturo, and Andrew Greenan’s sonorous Raimondo drew himself up to his full dramatic height. Pritchard pealed out the glassy high notes of her mad scene with an eerie intensity, while Grazia’s tone curdled chillingly in the final moments. There were a lot of school-age students in this matinee audience. First-timers? Their animated reactions as we headed back out into the daylight suggested that by the end, at least, they’d felt something of what opera can do.

A concert performance of Charpentier’s Louise, meanwhile, was what we were promised and a concert performance was what we got: orchestra in the pit, music stands on the stage and the entire cast – with the exception of a primrose-clad Madeleine Pierard as Louise – in black evening dress. “The lovely picture I want, the grace I ask, is no longer to be like a bird in a cage” sings the free-spirited heroine near the end of Act Four. As individual members of the Festival Chorus brought the forty-plus named characters in Charpentier’s vividly-imagined Montmartre street scenes exuberantly to life, it was impossible not to return to that thought. Everything about this glorious performance pointed in one direction: this is an opera that demands to be seen as well as heard.

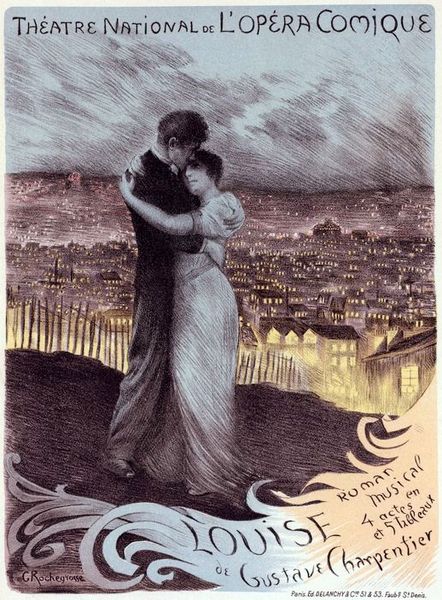

Louise was an international hit after its premiere in 1900 (poster pictured right), but it’s a rarity now – I knew it only through Georges Prêtre’s 1976 recording, and as the punchline to a joke in a Saki short story. In an excellent programme note, Henrietta Bredin describes Richard Strauss licking his lips with relish during a 1907 performance: as well he might. Louise is French verismo at its headiest, a sumptuous Alphonse Mucha poster of a score, written to the composer’s own remarkably sophisticated libretto and swept along on a tide of youth and joy, its ecstatic outbursts thrown into relief by a knowing wit and a tender but undeniable sense of transience.

Louise was an international hit after its premiere in 1900 (poster pictured right), but it’s a rarity now – I knew it only through Georges Prêtre’s 1976 recording, and as the punchline to a joke in a Saki short story. In an excellent programme note, Henrietta Bredin describes Richard Strauss licking his lips with relish during a 1907 performance: as well he might. Louise is French verismo at its headiest, a sumptuous Alphonse Mucha poster of a score, written to the composer’s own remarkably sophisticated libretto and swept along on a tide of youth and joy, its ecstatic outbursts thrown into relief by a knowing wit and a tender but undeniable sense of transience.

Stephen Barlow conducted it like a man in love, caressing each phrase, and pointing up successive re-appearances of Charpentier’s vaulting youth motif with playful enthusiasm. The Northern Chamber Orchestra responded with both ardour and delicacy, only very occasionally – in the throes of passion – overwhelming the voices on stage. Not that there was any risk of that with Madeleine Pierard. Her voice, in common with that of Adrian Dwyer as her bohemian lover Julien, has a youthful freshness that’s perfect for this role, but it can also open out, on the heights, into a great glowing arc of sound. Adrian Thompson brought a sinister combination of seduction and grotesquerie to his cameos as the fantastic Noctambuliste – the spirit of “the Pleasure of Paris” – while Susan Bickley was Louise’s mother: luxury casting for a thankless role, which she invested with something of the damaged humanity of the Kostelnička.

But the real tension in Louise comes from its psychologically acute portrayal of a young woman torn between her lover and her father, and in that role, Michael Druiett sang with such gentleness and compassion that the conflict had significant weight: the way his voice hardened and coarsened as he gave way to anger and then despair in the final scene made a domestic drama into a tragedy. As Pierard flushed, sulked, and - wide-eyed - pleaded, he seemed visibly crushed. Bickley, meanwhile sat by with a brittle, determined expression. And once again, you felt a full staging straining to fly free, like Louise herself, from the constraints of a concert performance. Louise needs to be back in the repertoire; and that discovery alone would have been worth the price of a trip to the Buxton Festival.

Add comment