"Touch her and you die," sings Masetto in telling Don Giovanni to keep away from his Zerlina. There's certainly trouble, though not instant death, when fingers briefly meet. Mozart's dark comedy has much in Da Ponte's text about hands-on business but only a few points where it's actually seen; love and sex don't really happen, though there are two skirmishes, one fatal.

The first image is a relief: not some putative sexual pleasuring or post-coital content between Don Giovanni and Donna Anna, but what Mozart, Da Ponte and their source, Tirso de Molina, meant it to be - an attempted rape, with the girl fleeing into the night. This Anna is young and vulnerable: a canny switch of the usual voice types has Mari Ericsmoen, superb recently in Bergen Schumann and Beethoven, a supple lyric soprano with sudden surprising shifts of gear into a more powerful mode, while lyric-dramatic Malin Byström (pictured below with Peter Mattei and Henning von Schulman), Donna Anna at the Royal Opera and a fine Salome, is cast as Donna Elvira, part of Giovanni's videotaped back catalogue. Both execute their big set pieces with perfect style, aided by swift, dramatic and still flexible tempi from Harding. Zerlina has an ideal characterisation, too, from Johanna Wallroth; Staples gets round the physicality implied in both her arias by having Masetto (von Schulman, also good) caress the screens on which she manipulates her appearance.  Dislocation and evasion suit the action, such as it can be, with sanitizer crucially to hand, while the Commendatore dies and Masetto is wounded within a circle at the front of the stage, somewhat mystically by switching off of the TVs. There's a 12-strong chorus, just right, and judicious use of balconies (frequently) and auditorium (once, when Staples' jealous and bewildered Ottavio sits out there and Eriksmoen's Anna delivers an exquisitely tormented "Non mi dir" with her back to him, essentically to herself as well as orchestra and conductor). Master and servant occupy and parry around the most space; Peter Mattei's Giovanni is a powerful force, utterly believable in suave lightening of the powerful baritone for wooing and persuading, relaxed and agile, with John Lundgren's Leporello more of an equal than usual.

Dislocation and evasion suit the action, such as it can be, with sanitizer crucially to hand, while the Commendatore dies and Masetto is wounded within a circle at the front of the stage, somewhat mystically by switching off of the TVs. There's a 12-strong chorus, just right, and judicious use of balconies (frequently) and auditorium (once, when Staples' jealous and bewildered Ottavio sits out there and Eriksmoen's Anna delivers an exquisitely tormented "Non mi dir" with her back to him, essentically to herself as well as orchestra and conductor). Master and servant occupy and parry around the most space; Peter Mattei's Giovanni is a powerful force, utterly believable in suave lightening of the powerful baritone for wooing and persuading, relaxed and agile, with John Lundgren's Leporello more of an equal than usual.

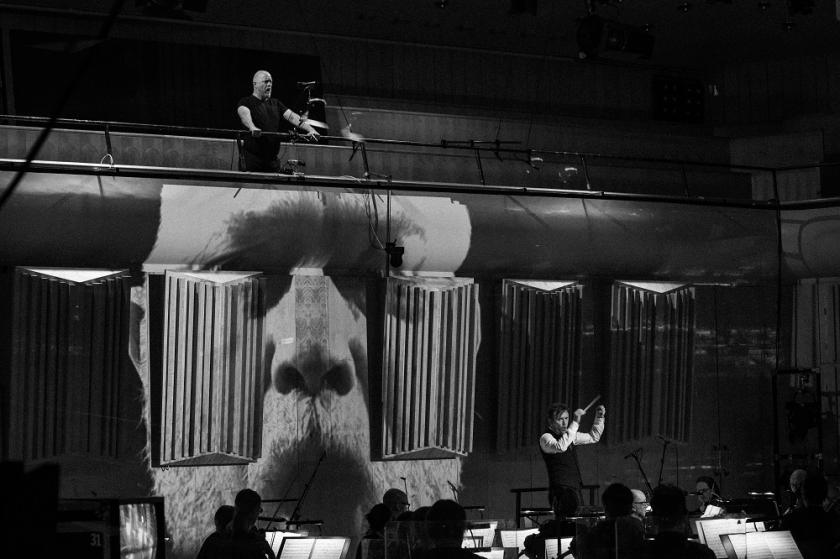

You just don't ask why a black wig will do for his impersonation while Giovanni passes as Leporello with a full head of hair. No matter; all the ensembles work, and the final sequence after the despatch to hell (pictured below: Staples, Eriksmoen, Lundgren, Byström, Wallroth and von Schulman) is swift and necessary, the seducer's face taking up the big screen at the back previously dominated by the "statue" Commendatore, whose mouth virtually devouring Harding. The energy is palpable throughout, and breathes an optimism of possibility in opera even at this seemingly impractical time.  Harding's earlier programme with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Choir and top mezzo Ann Hallenberg promised much in terms in innovation and challenge, but each component was diminished in its context (★★★). The idea was to punctuate the four movements of Sibelius's bleak, spare Fourth Symphony with other music of desolation and lamentation, as well as several poems - too few - on similar themes by the late, great national poet Thomas Tranströmer, read by Krister Henriksson (the original Swedish Wallander, and a compelling narrator of Tolstoy's text for a dramatised performance of Janáček's "Kreutzer Sonata" Quartet I heard in Gothenburg). It only served to convince me that Sibelius's rigorous unity can at the very most only take a break between the scherzo and slow movement; the first and second, then third and fourth movements have to be bound together.

Harding's earlier programme with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Choir and top mezzo Ann Hallenberg promised much in terms in innovation and challenge, but each component was diminished in its context (★★★). The idea was to punctuate the four movements of Sibelius's bleak, spare Fourth Symphony with other music of desolation and lamentation, as well as several poems - too few - on similar themes by the late, great national poet Thomas Tranströmer, read by Krister Henriksson (the original Swedish Wallander, and a compelling narrator of Tolstoy's text for a dramatised performance of Janáček's "Kreutzer Sonata" Quartet I heard in Gothenburg). It only served to convince me that Sibelius's rigorous unity can at the very most only take a break between the scherzo and slow movement; the first and second, then third and fourth movements have to be bound together.  It wasn't so much that Hallenberg seemed to get a rather bumpy ride from Harding in "The Lonely Man in Autumn", second poem of Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde, and that "Erbarme dich" from Bach's St Matthew Passion had nothing like the resonance it takes from the complete work; but that Purcell's Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary took up so much space - excellent in itself, with fine singing from the Swedish Radio Choir and shining brass- that we forgot the second half of the symphony was still to come. When you could put the breaks out of mind, as in the hypnotic tracing of steadily accumulating lines in Sibelius's Largo, from woodwind (superb) to arching full strings, problems evaporated; but the final payoff of the spectre overwhelming the feast simply didn't feel cumulative enough. Brave try, but it won't happen again in quite this way.

It wasn't so much that Hallenberg seemed to get a rather bumpy ride from Harding in "The Lonely Man in Autumn", second poem of Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde, and that "Erbarme dich" from Bach's St Matthew Passion had nothing like the resonance it takes from the complete work; but that Purcell's Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary took up so much space - excellent in itself, with fine singing from the Swedish Radio Choir and shining brass- that we forgot the second half of the symphony was still to come. When you could put the breaks out of mind, as in the hypnotic tracing of steadily accumulating lines in Sibelius's Largo, from woodwind (superb) to arching full strings, problems evaporated; but the final payoff of the spectre overwhelming the feast simply didn't feel cumulative enough. Brave try, but it won't happen again in quite this way.

- Watch Don Giovanni and the Sibelius plus ("Loneliness") concert on Swedish Radio's website

- More opera reviews on theartsdesk

- More concert reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment