Alcina, Glyndebourne review - Handel on the strand | reviews, news & interviews

Alcina, Glyndebourne review - Handel on the strand

Alcina, Glyndebourne review - Handel on the strand

High quality singing and playing on a dubiously coloured stage

Reviewing the Grange Festival production of Tamerlano the other day, I noted the difficulty Handel poses the modern director with his byzantine plots and often ludicrous love tangles, expressed through music of surpassing brilliance but mostly stereotyped forms. But at least Tamerlano is a comprehensible story with its feet planted firmly in a sort of reality.

In Alcina earthbound reality is hardly anywhere to be seen. We are on a magic island ruled by the enchantress of the title, who disposes of her many lovers by turning them into wild beasts or rocks, trees or rivers. Bradamante arrives (disguised as her brother Ricciardo) in search of her betrothed, Ruggiero, who is Alcina’s latest attachment, and who remembers nothing of Bradamante. Meanwhile Alcina’s sister, Morgana, falls in love with the supposed Ricciardo, while Alcina also seems to regard him as a possible successor to Ruggiero.

Bradamante’s teenage nephew Oberto appears looking for his father (presumably another of her brothers), who has been turned into a lion. And so it goes on. Like Tamerlano, Alcina issues dire threats to all and sundry but never quite carries them out, and in the end her power is broken by the breaking of the urn that contains it, she and Morgana vanish in a puff of smoke, and sanity of a kind is restored (pictured below, Jane Archibald as Alcina).

To take all this stuff seriously is nearly impossible, but Handel’s wonderful music, and in particular his treatment of the enchantress herself, compels us to try. Francesco Micheli’s solution at Glyndebourne is to read the piece, incestuously, as an allegory of theatrical illusion. Characters in modern business dress are invited by Morgana into what turns out to be a kind of vaudeville, in which they themselves have leading parts. At first we’re backstage: in the make-up room, in the bar, in the toilets (of course: unisex), but then on-stage. Alcina appears, the characters assume their designated roles, the action now makes sense, because, as we know, in the theatre all things are possible.

To take all this stuff seriously is nearly impossible, but Handel’s wonderful music, and in particular his treatment of the enchantress herself, compels us to try. Francesco Micheli’s solution at Glyndebourne is to read the piece, incestuously, as an allegory of theatrical illusion. Characters in modern business dress are invited by Morgana into what turns out to be a kind of vaudeville, in which they themselves have leading parts. At first we’re backstage: in the make-up room, in the bar, in the toilets (of course: unisex), but then on-stage. Alcina appears, the characters assume their designated roles, the action now makes sense, because, as we know, in the theatre all things are possible.

Whether or not this solves the problem, or merely pushes it back by one extra proscenium, is a moot point. The result, in Edoardo Sanchi’s and Alessio Rosati’s designs, and with magical lighting by Bruno Poet, unquestionably makes a vivid spectacle, with all the pink, yellow and purple vulgarity of a staged McGill cartoon, complete with one-piece swimsuits and ostinato peacock plumes. To say that it responds to Handel’s music, the acme of refinement, is stretching a point or two. It certainly wowed this Saturday-night audience.

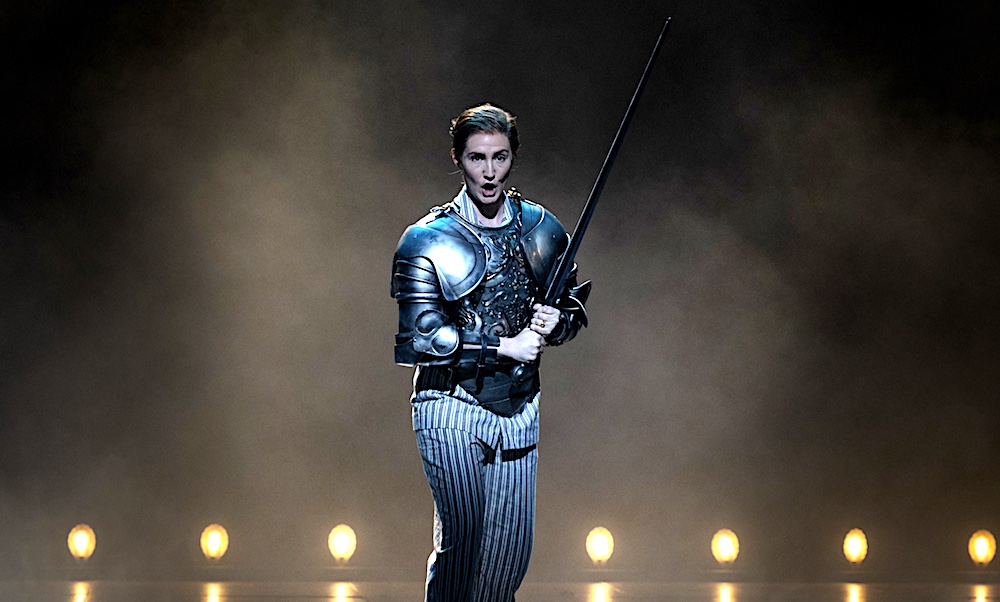

But the chief virtue of Micheli’s new production is that, by incisive portraiture, it to some extent clarifies the plot: no mean achievement, and perhaps not even a wholly desirable one, since the “plot”, such as it is, is monumentally silly. Less admirably, it clutters the stage with things and people, including the odd inexplicable doppelganger, and a corps of dancers who faff around in various ways, dance quite dully at the very end, but lose their curtain ballet in Act 2. Amid the family fun, perhaps the most beautiful moment is Morgana’s (Soraya Mafi’s) “Credete al mio dolore”, with its lovely, Bach-like cello obbligato, sung on an empty, mistily lit stage, followed by Stuart Jackson delivering Oronte’s “Un momento di contento” direct to us the audience.  The music, of course, redeems everything, and here doubly so because the singing is almost uniformly superb, varied in colour, and briskly paced under Jonathan Cohen, with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in tip-top form. As usual with Handel the soprano voice dominates, but here with nice contrasts: Mafi’s Morgana sparkling and athletic but with delicate half-tones, Jane Archibald’s Alcina fuller-bodied with an expressive vibrato that proclaims she is the one character in the show who – though it costs her her island and her magic – develops and learns emotionally. This is a fine, moving performance. Ruggiero, a castrato in the original, is here taken by Samantha Hankey (pictured above), a shade subduedly at first, but with exquisite feeling in “Verdi prati” and a certain splendour in “Sta nell’Ircana”, with its ringing obbligato horns. Oberto, composed, amazingly enough, for a 15-year-old boy at a time when the male voice broke later, is here a female soprano, Rowan Pierce, having a good shot at adolescent boyishness while singing with adult assurance.

The music, of course, redeems everything, and here doubly so because the singing is almost uniformly superb, varied in colour, and briskly paced under Jonathan Cohen, with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in tip-top form. As usual with Handel the soprano voice dominates, but here with nice contrasts: Mafi’s Morgana sparkling and athletic but with delicate half-tones, Jane Archibald’s Alcina fuller-bodied with an expressive vibrato that proclaims she is the one character in the show who – though it costs her her island and her magic – develops and learns emotionally. This is a fine, moving performance. Ruggiero, a castrato in the original, is here taken by Samantha Hankey (pictured above), a shade subduedly at first, but with exquisite feeling in “Verdi prati” and a certain splendour in “Sta nell’Ircana”, with its ringing obbligato horns. Oberto, composed, amazingly enough, for a 15-year-old boy at a time when the male voice broke later, is here a female soprano, Rowan Pierce, having a good shot at adolescent boyishness while singing with adult assurance.

Bradamante, by contrast, is Beth Taylor, a strong, dark mezzo with many colours in her voice. This must have been an odd reversal in 1735, with the castrato Ruggiero ranging appreciably higher than his fiancée: useful domestically maybe, but less helpful onstage. Meanwhile the true male voices inevitably come as a relief, but without condescension. The tenor Oronte, Morgana’s rejected then reconciled lover, is musically crucial, and sung here with great fluency and charm by Jackson. The bass, Bradamante’s old tutor Melisso, gets a shorter straw, a single aria only, but Alastair Miles, tall and authoritative, makes the best of it.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment